Skip to:

Shock wave lithotripsy (SWL) has become an increasingly popular treatment option to manage gall and kidney stones since its inception in the late 20th century. It is favored over surgical removal due to its non-invasive nature. However, like all surgical procedures, there are some safety concerns and potential sides effects that require consideration.

Shockwave therapy device. Image Credit: Cholpan / Shutterstock

What is shock wave lithotripsy?

SWL revolutionized the treatment of kidney stones in the 1980s, and its use has become increasingly common as standard-of-care in a number of clinical situations related to ureteral or renal calculi. One of the first commonly used shock wave generators was The Dornier HM3 which comprised a shockwave generator, large water bath, fluoroscopic imaging and ellipsoid reflectors. Since then, different types of shock wave generators have evolved. Currently, there are three main types; piezoelectric, electrohydraulic, and electromagnetic.

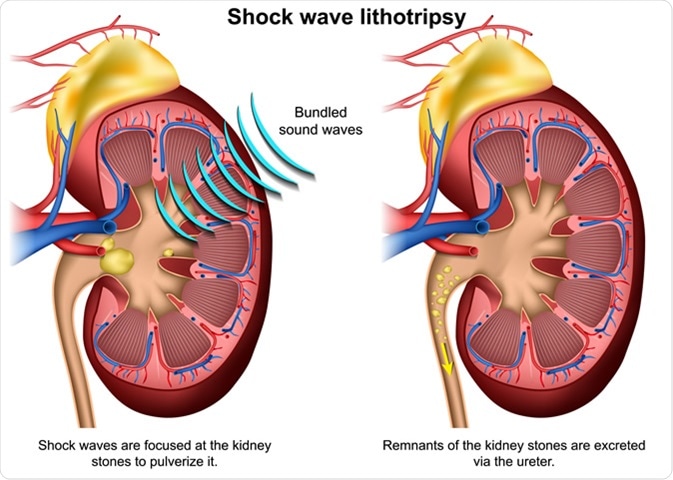

SWL uses large acoustic shock waves which are generated outside the patient’s body and then focused on the stones within the body. Due to a high focusing gain, lithotripters typically produce minimal damage to surrounding tissues by subjecting only the stones to high pressure. Furthermore, the use of fluoroscopic imaging allows practitioners to align the shockwave path with the stones, and focusing is achieved using ellipsoid reflectors.

The amplitude of the shockwaves used in the treatment are often in the range of tens of megapascals and they last for a few microseconds. The shockwaves are intended to break down the stones into smaller-sized pieces that can be easily passed out of the body through the patient’s urine. For some patients, more than one session may be required.

Shock wave lithotripsy 3D illustration. medicalstocks / Shutterstock

Safety of shock wave lithotripsy

The use of SWL is not advised in pregnant women or in patients with specific medical conditions such as non-functional kidneys, urinary tract infections, uncontrolled high blood pressure, obstruction of the stone path, and bleeding disorders which impair the blood’s ability to coagulate. Stone location, stone size, and overall stone burden are other factors that must be investigated before the use of SWL.

Other factors that can affect SWL safety and success include obesity, which increases the distance from skin to stone; stone composition; and stone density.

Even in patients without serious pre-existing medication conditions, certain considerations need to kept in mind to ensure the safety of SWL. For example, it is important to reduce the amount of damage to the surrounding organs. Therefore, practitioners need to ensure that they set the device for the shock rate to be just high enough to be optimally effective without increasing the number of sessions. This will mean a reduced number of shocks per minute, reducing the chances of parenchymal damage to the organ.

Shockwave lithotripsy

What are the side effects of shock wave lithotripsy?

Like all medical procedures, SWL may be associated with a range of side effects depending on the position and size of the patient’s stones.

Tissue damage

Despite the best attempts to reduce the amount of damage to the tissue surrounding the stone, it may not be completely avoidable. In SWL, this damage is most in the form of trauma localized to the area around the treatment target. Most of the literature investigating tissue damage understandably focuses on the effects on the kidneys. However, later research has found that areas further afield may be affected. For example, findings have shown that rupture of the spleen, liver, and abdominal aorta may occur besides perforation of the colon.

Hematuria

It has been reported that the majority of patients who undergo SWL will experience the passage of blood in the urine, otherwise known as hematuria. As the occurrence of hematuria is so commonly experienced, most consider it to be an incidental finding. In fact, some experts even consider the presence of some blood in the urine to be an indication of the correct alignment of the shockwaves with the kidney.

Infection

During SWL, a cavitation bubble collapses to exert force on the target stones. This can cause damage to the blood vessels within the kidney and result in microhemorrhage. This, in turn, may lead to the passage of bacteria present inside the stones or in urine into the bloodstream, in turn causing infections such as sepsis and urinary tract infections. The former is quite rare, while urinary infections are also more common in the presence of other risk factors like a staghorn calculus or instrumentation along with the SWL.

Incomplete fragmentation and obstruction

SWL typically aims to break stones into smaller-sized fragments that can be passed out of the body. Sometimes the procedure may not be completely successful and results in partial fragmentation of the stone. This can be corrected by repeating the procedure after a while. However, partial fragmentation may cause pieces of the stone to block the ureter, which may require additional medical attention.

Shock wave lithotripsy has become one of the most popular non-invasive treatment methods for stones within the body. However, like many procedures, there is a range of safety precautions and side effects that should be communicated with patients.

Sources

- D’Addessi, A., Vittori M., Racioppi M., et al. (2012). Complications of Extracorporeal Shock Wave Lithotripsy for Urinary Stones: To Know and to Manage Them – A Review. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1100/2012/619820

- Reynolds L. F., Kroczak T., & Pace K. YT. (2018). Indications and contraindications for shock wave lithotripsy and how to improve outcomes. Asian Journal of Urology. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajur.2018.08.006

- Averkiou M. A., & Cleveland R. O. (1999). Modeling of an electrohydraulic lithotripter with the KZK equation. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. DOI: 10.1121/1.427039

- Elmansy H. E., & Lingeman J. E. (2016). Recent advances in lithotripsy technology and treatment strategies: A systematic review update. International Journal of Surgery. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.11.097

Further Reading

Last Updated: Jul 21, 2019