In the past, caloric sweeteners simply referred to cane sugar or beet sugar. However, over time we've created hundreds of different sugars that are all providing calories of the same amount, about four calories for every gram of the sugar. Some examples include corn syrups and more processed sweeteners like high fructose corn syrup.

Other examples include Turbinado, which is a kind of a variety of cane juice where fruit juice is concentrated and then the sugar is taken out of it. Sorghum, a sugar from the grain sorghum, is another one used.

How are low-calorie sweeteners defined?

Low calorie sweeteners may have a tenth or a hundredth of a calorie in that same gram of sweetener. Almost all that are used by the food industry are very intense in their sweetness flavor.

A generic example is aspartame and there's around fifty of them on the market that are approved. In the last couple of years a couple of new ones have been described as “natural". The reality is every one of them contains minimal calories but provide a much greater and more intense sweetness effect than regular sugars so most products use much less of them.

How many packaged foods and drinks in the US contain caloric and low-calorie sweeteners? How does this compare to the rest of the world?

Between 2000 and 2013 we had 1.2 million different packaged foods, however many of them are different sizes of the same item or packed in different ways, like a multi-pack of a cereal for example.

The actual number in 2013 was around 130,000 different formulations of food and beverages that were packaged and processed. Of those in the US, about 90,000 or 69% in 2013 had some kind of caloric sweetener added to them.

The US is very similar to the UK in terms of our food supplies and the amount of processed food we consume.

When you go to Europe there's bigger tendencies to use fruit juice and organic, natural sweeteners that people think are healthy but really they're just another sugar.

When we move into Latin America, now the retail sector covers about sixty percent of the diet with packaged and processed foods so that it's a little bit below what the US and UK have, but not much.

Consumption in Asia is growing and it’s predicted that within another five or eight years, Asia will look like Latin America. In some countries in Asia, like China, packaged processed food sales have grown thirty-five to fifty percent each year in the past decade.

Urban Africa is also rapidly becoming a retail sector and you now find most villages in Africa have small convenience stores with the same kind of packaged and processed food. The reality is this is very rapid growth in Africa.

Can consuming foods and beverages with added caloric sweeteners lead to increased risk of weight gain, heart disease, diabetes and stroke? How much evidence is there?

Yes, they significantly increase the risk, particularly for diabetes. In addition to the diseases you mention, they also increase the risk for nine of the top thirteen cancers.

The World Cancer Research Federation has also done major reviews that says that the abdominal obesity related to the sugars makes reducing consumption of added sugar one of the top couple of preventable ways to prevent cancer.

The consensus exists across the World Health Organization, the NHS in the UK, the US Dietary Guidelines and the Institute of Medicine in the US. We should have no more than ten percent and hopefully five percent of our calories from added sugars in our diet because of the health risks.

The risks are quite great. The sugar goes and is metabolized, half of it in our liver, and it directly creates a lot of problems that relate to things like additional fat around the heart and the liver.

Consumption of excessive sugar, as we know for diabetics, is really very bad. Our bodies process the sugar very quickly, there is a rapid spikes in our insulin level and it increases the complications from diabetes greatly.

What initiatives is the World Health Organization (WHO) promoting to reduce intake?

They have promoted three large-scale regulatory efforts:

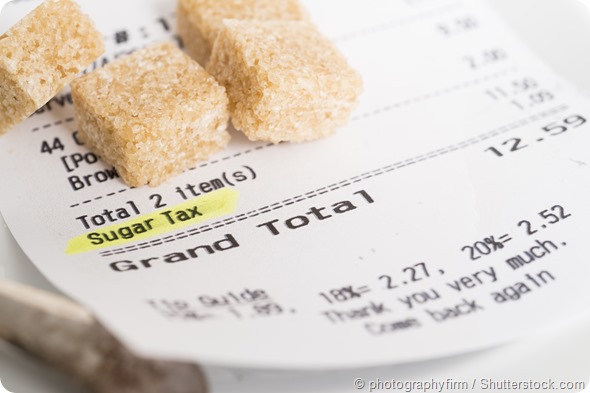

- taxing first sugary beverages, secondly considering taxing junk food and other food very high in sugar

- marketing bans on these kind of unhealthy foods and beverages

- adequate labeling the front of food packaging to clearly identify the food as very excessive in sugar or not of high quality

How successful have these initiatives been so far?

So far only three countries have put in major taxes. Mexico and France have each put in about a 10% tax on sugary beverages, much less than we recommend to make an impact.

In Mexico there’s been a very rigorous evaluation of the tax. In the first year, there was a 6% cut for the whole year consumption of sugary beverages. By the end of the year there was a 12% reduction in sugary beverages and a much higher increase in water purchases.

A paper published in the prestigious British Medical Journal in the beginning of January showed that the impact of a 10% tax, half of what the Mexicans thought they needed to make an impact on weight and diabetes, still has a significant effect, but it will take a long time for the cumulative effect of that to set in because it's so small.

France has not evaluated yet its tax. Hungary had a somewhat smaller tax on junk food, which did have a significant effect on purchases of those products. There are three to five countries today considering much higher taxes and within a year we'll probably have a 20-30% tax on soft drinks in one to two other countries.

What challenges still exist for policy makers?

The problem of course is that food companies are very big and in general the food industry does not want to be regulated. They say they'll do it by themselves, of course the proof of the world gaining the weight it’s gaining and all the cardiovascular disease and cancers coming from our diet show that that's not the case.

The food companies put a lot of energy and lobbying money into trying to prevent taxation and other regulation. That's why it's been slow, but the Mexican tax and the result of it has incentivized many other countries. In the US, a large of number of counties and cities will be considering going after taxing sugary beverages because of the Mexican experience.

We talk more about sugary beverage intake because when you consume a beverage with calories you do not cut your food intake down at all. What that means is those sugary beverage intakes are just adding extra calories. Not only are they adding the sugar, but they're adding extra calories to your diet which is why it is such a significant effect.

Whereas when you consume a candy bar, usually you cut other foods. You compensate for it so that its effect is too much extra sugar and unhealthy saturated fat, but it is not adding extra energy to the extent that would happen when we consumer caloric beverages. That's why the biggest focus to date has been on the caloric beverage side.

I'd say that just like with tobacco it's country by country. There are three or four other countries that have a tax that haven't evaluated them yet. In addition to taxes, Chile will be adding a marketing ban, so that will be evaluated by our team and then we'll understand what effect those two things in combination will have on cutting consumption of unhealthy beverages.

Why is there no current global consensus on the healthiness of fruit juices and drinks containing low-calorie sweeteners?

Fruit juice is seen by the world as being natural. At one point we said, "Eat five a day, fruits and vegetables or drink fruit juice." We very quickly realized that from the unbiased studies that have been done that fruit juice acted just like soft drinks.

It essentially is instead of consuming one or two apples or oranges and filling yourself, you're consuming a glass of six or eight oranges and it's all sugar water with some flavoring in it and a little bit of fiber.

We don't compensate by cutting our calories so that the very large long-term cohort studies that have looked at fruit juice effects in Europe, Singapore and the United States have found an increased risk of diabetes and other problems related to fruit juice consumption. However, we have not put the money into much more definitive research such as random control trials so that to date we've not been able to create a consensus in its impact.

When we turn to the diet sweeteners, the low calorie sweeteners, this is a much more complex story. Part of it is there's only been two random control trials and both of those have shown that the caloric sweeteners have no adverse effect on health.

They don't increase weight, they don't increase the risk of cardio-metabolic problems. These trials were undertaken in Denmark and the US.

However, the second part of that is that we have many long-term cohort studies that have ignored what people eat. We tend in the US and the UK and Europe to have two groups of people consuming diet beverages in particular.

One group would be the healthy eaters that consume diet beverages are part of trying to eat a healthy diet. The other group would be what I might call the Big Mac or pizza and Diet Coke group. That group consumes the unhealthy beverage but has a very unhealthy Western diet.

In the studies which controlled for the food intake and looked at the effects of diet sweeteners among the healthy eaters they found a significant reduction in risk of all the different metabolic problems you talked about: diabetes, heart disease, hypertension and so forth.

On the other hand, most of the cohort studies that have been done ignore the diet so they don't really look at the interaction to see that there's one sub-population that consumes diet sweeteners unhealthily.

If you ignore that, you will find that diet beverages are associated with increased risk of heart disease because that group that consumes the unhealthy diet, Diet Coke is not going to help them out. A very large proportion of diet beverages consumers eat a very unhealthy diet today.

The other thing about diet sweeteners is there have been bloggers that talk about the risks of them. All the reviews that have been done by our Environmental Protection Agency, our Food and Drug Administration, the Food Standards Agency in Europe and many others cannot find any evidence.

When they look at the little tiny groups that have produced these studies and they ask to see the data, they can't produce the data to back up their claims that items like aspartame, which have been around for forty or fifty years, cause cancer.

To date we have no evidence that the long history of these diet low calorie sweeteners, that they are toxic in any way, have any unhealthy effect in terms of risks of cancer or other problems from a purely toxicological perspective.

So what should we be drinking?

The reality is drinking water is better. Drinking tea, coffee and water are the healthiest beverages. After that for adults, consuming red wine or other alcoholic beverages in moderation. It's not like we want people to drink diet beverages, but we want them to understand that when they drink them, if they eat a healthy diet, it will help their health. It will not hurt them.

What do you think the future holds for the global diet?

There's two issues here. The current future, the way the global diet's going across the world, there's a rapid increase in what I call ready-to-eat or ready-to-heat foods, convenience foods. They could be bars and cereals that you can eat right away or they may be items you need to heat up, frozen dinners or things you purchase in the store that you take home and heat up. That's been a massive change.

On the other hand, we have this push both in Europe and in the US and increasingly in some low income countries to go back to a more traditional way of cooking food and eating real food.

These two different pushes are clashing. Right now, the retail sector's winning out. By far the biggest growth is in proportion of the world's population and the absolutely numbers consuming processed packaged foods.

There certainly is a push to eat healthier real food, but it's so far affecting mainly upper educated populations in the US and Europe of consuming and cooking and going back to eating real food only or mainly real foods such as fruits and vegetables, poultry, fish, meats that you can buy in the store and then cook them.

I'd say right now the future holds for the global diet essentially a worsening of what we have, except for the countries that are now seriously adding many, many regulatory efforts to try to change the diet. We do not know what will happen from those.

Chile's a global leader in attempting to create a healthier diet. First they instituted the beverage tax. They're now instituted a ban on marketing to children of unhealthy foods and beverages. Very soon, they're going to implement a law that's been passed to ban all unhealthy food marketed to all groups between 6am and 10pm, which is all encompassing and includes all media, movie, TV, and the internet which display any of these unhealthy foods so that marketers will only be able to market what they term healthy foods, which are lower in sodium, added sugars, unhealthy fats and calories.

We don't know how these regulations in countries like Chile, France and others are really going to impact our diet. It's part of the global push by countries to try to control the really health costs which are kind of running out of control in terms of obesity, diabetes and all the cancers.

The cardiovascular disease and the cancer growth is really high. In the US, our current generation of children will live a shorter life than current adults because they are so heavy and obese. We're quite concerned.

The actions are taking place right now in countries with a higher level of social consciousness like Latin America. They're starting to be implemented in other parts of the world too. We are going to be seeing in the next five years major battles in more and more countries as they try to implement strong regulations to reduce our intake of these high sugar products, particularly beverages but also foods.

Where can readers find more information?

The World Health Organization reviews and their report on added sugar is very helpful.

There's been a similar kind of review done by the World Cancer Research Federation.

There have been the US Dietary Guidelines scientific report, the report that's come out from the health services in the United Kingdom on added sugars and sugar's effect.

All of these are reviewing the science and there are many websites that give people guidance on ways to cut added sugar from their diet. I should add it's added sugar. Natural sugar in fruit and milk is fine, we can't get too much of that. When we take that sugar and we concentrate it like in a juice or a soft drink or in candy or cake, we bring to see the health risks. Not when it's natural in food.

About Professor Barry Popkin

Barry M. Popkin, PhD, is the W. R. Kenan, Jr. distinguished professor of nutrition at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC). He has a PhD in agricultural economics and established the Division of Nutrition Epidemiology at UNC and later established and ran the UNC Interdisciplinary Obesity Center, funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

He has developed the concept of the Nutrition Transition, the study of the dynamic shifts in dietary intake and physical activity patterns and trends and obesity and other nutrition-related noncommunicable diseases.

His research program focuses globally on understanding the shifts in stages of the transition and programs and policies to improve the population health linked with this transition (see http://www.nutrans.org). His research is primarily funded by the NIH.

In the U.S., Popkin’ s work involves long-term research focused mainly on dietary and food purchasing behavior, the underlying determinants of patterns and trends in these behaviors and their linkages to obesity and other noncommunicable diseases. This includes an array of research focused on retailer behavior.

He leads the Global Food Research Program of UNC(GFRPUNC), which has developed a method to monitor changes the entire factory to fork food system and is using this to evaluate global food company activities as well as those of retailers and their impact on our diets.

In the US the GFRPUNC focuses on race-ethnic disparities, other behavior monitoring the packaged purchased food industry and various smaller efforts such as joint evaluation with a partner of the impact of the Berkeley sugar-sweetened beverage tax (SSB).

Also in the US he is working with several groups that focus on food retailer interventions. He Chairs an International Scientific Committee for Choices International Foundation that focuses on promoting in countries across the globe and with both caterers and retailers in many countries on Front-of-the-Package (FOP) profiling. He is working with a number of global retailers in this role.

Popkin’s GFRPUNC is equally large-scale. This includes directing longitudinal surveys in China and Russia and other survey work across all regions of the low and middle income world. He is actively involved at the national and global level in policy formulation for many countries, particularly Mexico, South East Asia, and China. He has played a central role in placing the concerns of global obesity, its determinants, and consequences on the global stage and is now actively involved in work on the program and policy design and evaluation side at the national level, including collaborative SSB/junk food tax evaluation research in Mexico (with the National Institute of Public Health) in evaluating the impact of the Mexican SSB and nonessential food taxes and similar work with the Institute of Nutrition and Food Technology, University of Chile in evaluating an SSB tax and marketing/FOP controls. Again these studies and evaluations include research on specific retailer behavior.

He has received a number of major awards for his global contributions, including: Gopalan Award, India; UK Rank Science Prize; U.S. Kellogg Prize for Outstanding International Nutrition Research; and The Obesity Society Mickey Stunkard Lifetime Achievement Award. He has published over 490 refereed journal articles, is one of the most cited nutrition scholars in the world, and is the author of a new book entitled The World is Fat (January 2009, Avery-Penguin Publishers), translated into 11 languages.