Telemedicine is the art of improving patient care via managing data remotely, and in this spirit one of the earliest examples often not considered in this category, would be the permanent pacemaker, first implanted into a human being in 1958.

Pacemakers not only collected data from the heart’s electricity remotely, but in line with programmed responses, they treated slow heart rates with artificially generated electrical firings and stored these data to be made available to cardiologists at a later date.

Since then, we have strived and succeeded in the ability to cross communicate between these devices remotely, to manage patients with increasing range of complexities to the point of delivering life-saving shocks as needed. To me this is telemedicine at its pinnacle.

What are the main challenges of telemedicine from a security and safety perspective?

As we become an increasing, device-dependent society, we risk the issues of negative hacking and putting our health and lives at risk.

As with cyberattacks previously on banks, personal mobiles and on company sites, attacks could be targeted to the data from patients’ medical devices, or from health tracking devices worn by people in a location or even wellbeing and stress monitoring devices worn by company employees.

Misrepresenting a company’s executives as under stress ‘wrongly’ could shift stocks and shares and contracts in the wrong direction and damage the company or its projects.

Alternatively on a positive note, sensing doctors and nurses in a particular emergency department were under undue stress could allow emergency ambulances to bypass that hospital until matters improve.

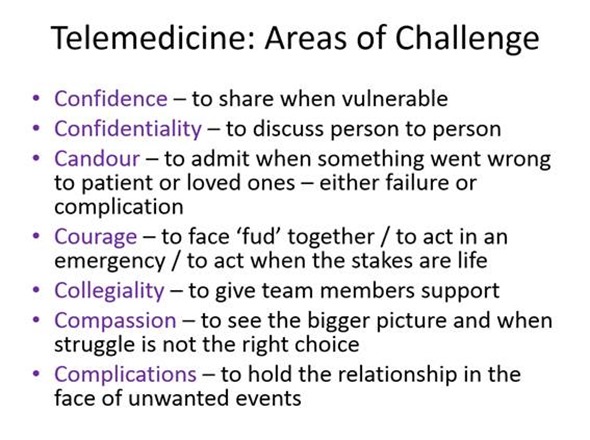

The additional challenge as always remains, in how best to use telemedicine with technologies appropriately without losing the human element of person and caregiver within that framework.

In Telemedicine, we risk people becoming numbers and data only and the value of the relationship between people is not accountable.

What’s your heart rate becomes a bigger issue than what’s your health like? This is key to appreciate as people are much more than the sum of their numbers and data.

How do we make sure telemedicine doesn’t minimise human-human interactions but instead enhances them?

Increasingly there are tasks undertaken that have little direct, benefit on a person or a clinician, for example logging prescriptions or writing down findings or coding diagnoses or ordering tests manually or copying the data to another clinician.

All such tasks can be minimised with the use of smart technologies and assistive systems. They can observe, record, interpret, accept verbal commands allowing the clinician and person patient to spend more time together to provide those key aspects of treatment also always needed – insight, confidence, compassion, eye contact, exchange of smiles and care, in addition to the medications and procedures prescribed.

What do you think the future holds for telemedicine?

Telemedicine is inevitable as people become impatient to have answers and knowledge, wherever they are and whenever they require it.

Telemedicine will become like conjuring the genie from Aladdin’s lamp. We’ll be able to conjure virtual doctors, nurses, pharmacists, counsellors and health advocates or coaches using our mobile devices or via holographic projectors.

Access to telemedicine will be as easy as access to a telephone used to be. Drones can then deliver therapies or diagnostic devices.

In the future, telemedicine will enable to act more early on our health needs and we will be able build relationships hopefully without such long delays as in the current system.

Our health should then see improvements due to rapid and early diagnostics from a range of devices managed remotely by expert medical engineers and technology manufacturers.

Telemedicine may even support our ability to do prevention better. However on the flip side, it will undermine our own confidence to be able to heal naturally, to be independent and self sufficient.

We may become conditioned to seek advice on every change in our body and as we gain more and more comfort from others, we become accustomed to a communal way to approach any problem. We may become undermined to be independent.

How do you think telemedicine will impact the clinician’s role in patient care?

Initial telemedicine will hamper clinical care, given that large amounts of data will be generated and collected and need analysis and input. Much of this data may be normal and not be meaningful. Only a few percent of data may be useful.

As systems evolve to sift the uninteresting data from the interesting, focusing on key events or changes in remote data, we will start seeing faster and earlier decision making for the care of the people under the care of the telemedicine technology such as a cardiac monitor.

What changes do you think need to be made to the NHS in order to accommodate telemedicine and increase its adoption?

The NHS needs innovation accelerator champions to be as common as health care managers. These individuals can share, promote and spread best practice rapidly and keep revising our systems to improve patient outcomes and reduce needless wastage of time and energy of good clinicians. These individuals could also promote prevention services deployed by the use of telemedicine solutions.

With greater investment in prevention, we can change the face of the NHS. To enable this, however we may need to work alongside these champions in a commercial fashion, so that while they work in their companies, the NHS closely collaborates with them.

Indeed if more of our NHS funding could be moved from management salaries to innovation and transformation projects, the NHS may evolve at a pace that technology is evolving.

How important do you think wearables will be in the future of medicine?

Wearables will be critical to medicine. I believe we are at the crux of new technologies becoming affordable to a wide range of people. This will further bring prices down and make wearables as accessible as mobile phone which in themselves are becoming wearable.

I like to coin the terms as moving from hardware and software to bodywear and bloodwear. Wearable devices currently exist that can detect heart attacks and stroke early and other wearables are even therapeutic, such as the wearable cardiac defibrillator vest or a breathing training device to reduce asthma attacks. Wearable will become a major shift possibly even threatening clothes to become health functional.

Where can readers find more information?

I tend to come across news on medical technologies in medical sites like Medscape or see innovations at conferences like Wired Health or Digital Health and even some of the large mobile phone expos and then there are Medtech blogs such as Fierce BioTech or Qmed resources and The Royal Society of Medicine now have sections on eHealth also.

About Dr Ameet Bakhai

Ameet Bakhai is a front line consultant cardiologist, and local lead for care of patients with ‘heart failure’. A renowned international researcher, he has expertise in Clinical Trials Design and Analysis as well as Health Economics, Technology Appraisal, Clinical Innovation and Redesign of Patient Treatment Pathways and Guidelines.

As deputy director of Research at Royal Free London NHS Trust hospitals, he oversees over 90 research staff working on 300 active trials. Extensively published and author of several clinical textbooks, he’s also often the first to introduce new technologies; he began the first London ultrafiltration programme in coronary care unit for heart failure patients, was the first to train a dedicated cardiology physician associate in England and recently had the first patient started on the drug Entresto in Europe. Essentially, he is passionate at advancing the use of smart solutions and technology wherever it can benefit patients and improve care systems.