Nov 8 2016

Huntington’s disease is a neurodegenerative disease that is presently incurable. Scientists around the world are researching its causes and molecular processes in the attempt to find a treatment.

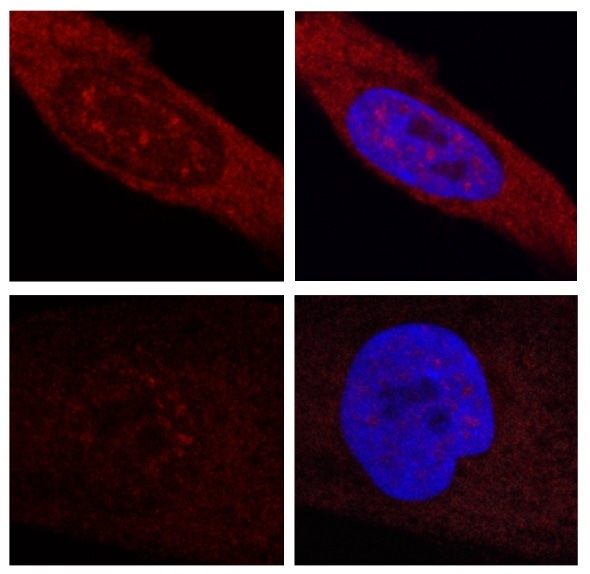

Fluorescent detection of foci in red fibroblasts of patients with Huntington’s disease. Up: cells showing mutated RNA foci. Down: Cells with blocked RNA do not show foci.

The research just published by a group of scientists from the Centre for Genomic Regulation (CRG) in Barcelona, Spain, led by Eulàlia Martí, in cooperation with researchers from the University of Barcelona (UB) and August Pi i Sunyer Biomedical Research Institute (IDIBAPS), has brought to light new information on the molecular mechanisms that cause Huntington’s disease, and defines new pathways to therapy discovery. The results of the study are published in the November issue of the Journal of Clinical Investigation. Eulàlia Martí is the lead author, while Laura Rué and Mónica Bañez are its first authors.

Huntington’s disease is caused by the excessive repetition of a nucleotide triplet (CAG) in the Huntingtin gene. The number of CAG repetitions varies from person to person. Healthy individuals can have up to 36 repetitions. Nevertheless, as of 36 repetitions, Huntington’s disease develops. The direct consequence of this excess of repetitions is the synthesis of a mutated protein–different from what would be obtained without the additional CAG repetitions–which has been considered the main cause of the disease for the past 20 years.

“What we have observed in our study is that the mutated fragment acting as a conveyor–the so-called messenger RNA–is key in the pathogenesis,” says Dr. Eulàlia Martí, lead author of the research project, together with Xavier Estivill, and acting group leader of the Genes and Disease laboratory at the Centre for Genomic Regulation. “The research on this disease being done by most groups around the world seeking new therapeutic strategies focuses on trying to prevent expression of the mutated protein. Our work suggests that blocking the activity of messenger RNA (the “conveyor”), would be enough to revert the alterations associated with Huntington’s disease. We hope this will contribute to improving the strategies in place to find a cure,” states the researcher.

Going deeper in molecular mechanisms enables progress to future applications

This work underscores the importance of rethinking the mechanisms behind illnesses in order to find new treatments. The work of scientists at the CRG has helped explore the molecular mechanisms that cause the disease. Now, their results will contribute to better delimit research efforts towards a cure.

As opposed to most other research groups, Eulàlia Martí’s team has sought to identify whether the problem resided in the messenger RNA – which would be the copy responsible for manufacturing the protein – or in the resulting protein. Prior work indicated that mRNA produced, in addition to defective protein, other damages. This previous work was the starting point for Martí and her fellow researchers, who have finally demonstrated that mRNA has a key role in the pathogenesis of Huntington’s chorea. “The research we have just published points to RNA’s clear role in Huntington’s disease. This information is very important in translational research to take on new treatments,” says the researcher.

More in-depth studies on these mechanisms are yet to be done. For example, research must explore whether it will be possible to revert the effects of Huntington’s disease in patients, just as researchers have demonstrated in mouse models. It also remains to be seen whether the proposal of the CRG researchers can be used in a preventive way, as the disease does not generally appear until after 40 years of age (in humans). Despite the remaining gaps, the published work makes for a key step in knowledge of the mechanisms of this neurodegenerative disease that, as of today, remains incurable.