This article is based on a poster originally authored by Yingying Fu, Zhen Qi, Zhanguang Zuo, Spencer Chiang, An Ouyang, Glory Gao, Shuge Guan, Jessie Chen, Rosanna Zhang, and Cheng Wang.

Existing organoid approaches typically lack some physiological cell types, standardized protocols, and translatable biological assays despite promising advancements in drug development and disease modeling to reduce elevated failure rates of clinical drugs even following preclinical testing (Kim et al., 2020).

Organoids remain the gold standard of preclinical drug development models due to their translatable human genomic background, which mimics their corresponding organs’ 3D architecture, function, and high-throughput capacity (Zhao et al., 2022).

Using organoids as pre-clinical models could considerably enhance drug development efficiency and diminish the need to use animal models, which are frequently unable to correspond with human responses.

ACROBiosystems has engineered a new, commercially available, hydrogel-free human induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived assay for cardiac and cerebral organoid systems.

Cerebral and cardiac organoids contain various cell types identified through marker immunolabeling and RNA sequencing. They display functional properties of the organs they model, confirmed by techniques like patch clamp, multi-electrode array (MEA), and silicon probe recording.

A Parkinson’s disease model was generated by adding alpha-synuclein pre-formed fibrils to the cerebral organoids. The cardiac organoid was utilized to check drug cardiac toxicity. The two organoids emerged as potential adeno-associated virus (AAV) screening models for gene therapy advancements.

These developments offer an improved understanding of disease and toxicity modeling and gene therapy progression when conducting clinical studies.

Methods and materials

Organoids were engineered using commercially bought human iPSCs (Cat. No. ACS-1007, ATCC) utilizing any Cerebral and Cardiac organoid kit from ACROBiosystems (Cat. No. RIPO-BWM001K, RIPO-HWM002K) according to the protocol highlighted in the datasheet.

Harvested iPSCs were seeded onto a 96-well ultra-low attachment plate, where embryoid body formation was tracked. Cells were administered with the necessary media provided in the kit to encourage organoid formation and cell differentiation. Organoids were used for assays at the specified time points.

Organoids were fixed, permeabilized, and immunolabeled with the specified cell markers for confirmation. For the model of Parkinson’s disease, cerebral organoids were administered with 0.1 µM and 1 µM alpha-synuclein pre-formed fibrils (Cat. No. ALN-H5115) on day 92 for 12 days.

For the cardiac toxicity model, cardiac organoids were administered with various concentrations of drug A (drug name confidential) on day 25. For AAV transduction, cerebral organoids (101 days) and cardiac organoids (11 days) were transduced with 1011 vg of eGFP transgene carrying AAV5 WT as negative control or with amended AAV serotypes comprising IVB-1, IVB-2.

All organoids were incubated at 37 °C, 5 % CO2, shaking at 100 rpm until available for later assessment.

Results

Characterization of cerebral organoids – cell marker verification

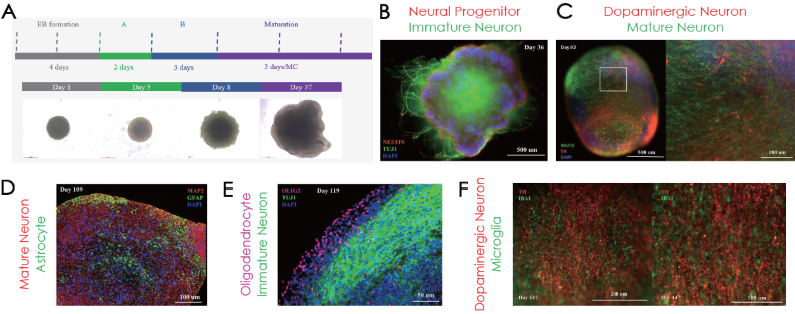

Human iPSC-derived cerebral organoids generated via a Cerebral Organoid Differentiation kit (Fig. 1A) were defined by immunolabeling for neural progenitor and immature neuronal cells on day 36 and at later culturing stages for dopaminergic neurons and mature neurons (day 92), for astrocytes (day 109), for oligodendrocytes (day 119) and microglia (day 147) (Fig. 1B-E).

Figure 1. (A) Cerebral organoid differentiation timeline. Immunofluorescence confirmation of (B) NE STIN and TUJ1, (C) MAP2 and TH, (D) GFAP, (E) OLIG2, and (F) IBA1 positive cells on different stages of organoid maturation. Image Credit: ACROBiosystems

Characterization of cerebral organoids – transcriptomic and functional characterization

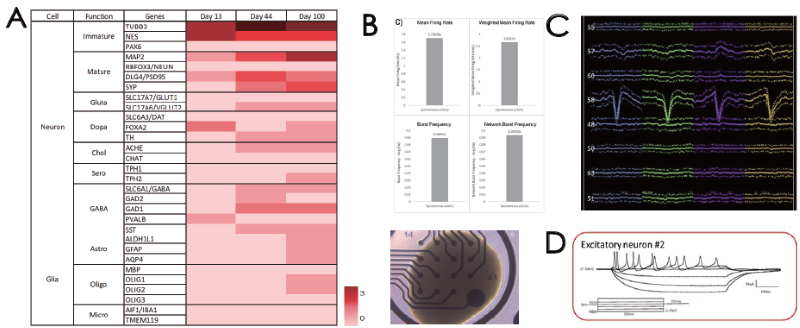

Cerebral organoids have multiple neuronal subtypes and glial cell types, as confirmed by bulk RNA sequencing (Fig. 2A). They also exhibit extracellular electrical activity, as confirmed by (B) MEA analysis and (C) silicon probe recording. Silicon probe recording further demonstrated numerous neuronal groups in early network activity and (D) intracellular electrical activity, as confirmed by the patch clamp.

Figure 2. (A) Transcriptome profiling of cerebral organoids. Extracellular electrical activity by (B) MEA and (C) silicon probe recording. (D) Intracellular electrical activity by patch clamp. Image Credit: ACROBiosystems

Parkinson’s disease and AAV capsid screening modeling on cerebral organoids

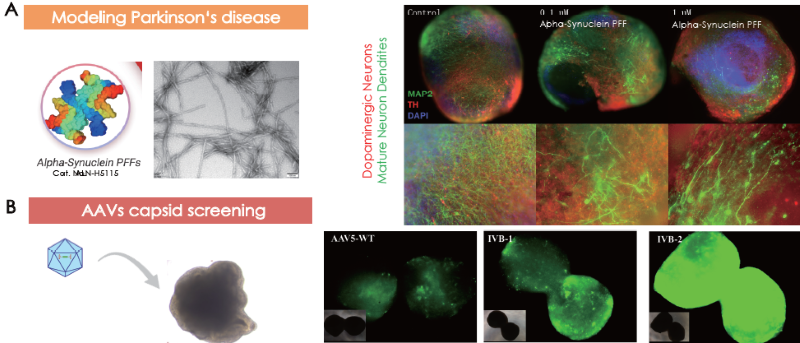

Treating healthy 92-day-old cerebral organoids with alpha-synuclein pre-formed fibrils for 12 days (Fig. 3A, left) led to concentration-dependent dopaminergic neuron degeneration and disruption of other neuronal dendrites (Fig. 3A, right).

Cerebral organoids cultivated for 101 days were administered with AAV5-WT, IVB-1, and IVB-2. The IVB-2 subtype demonstrated elevated infectiousness and transgene delivery towards cerebral organoids.

Figure 3. Cerebral organoids as models for (A) Parkinson’s disease and (B) AAV capsid screening. Image Credit: ACROBiosystems

Characterization of cardiac organoids – cell marker verification

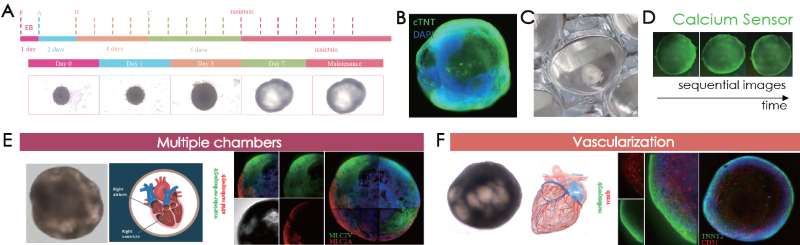

Human iPSC-derived cardiac organoids generated via Cardiac Organoid Differentiation kits (Fig. 4A) were defined via immunolabeling for cardiomyocytes on day 12 (Fig. 4B) and mechanical beating (Fig. 4C, beating not displayed). Mechanical beating is observable following day nine of culturing in cardiac organoids - calcium sensor imaging verified calcium flux behavior in the human heart (Fig. 4D).

Structurally, ACROBiosystems’ cardiac organoids display ventricular and atrial-like chambers in various areas, further confirmed through ventricular and atrial cardiomyocyte markers (Fig. 4E). The presence of endothelial cells was verified on the cardiac organoids (Fig. 4F)

Figure 4. (A) Cardiac organoid differentiation steps. Immunofluorescence confirmation of (B) cTNT and (C) visualization of cardiac organoids on tissue culture plates. (D) Sequential images of calcium sensor imaging of cardiac organoids. (E) Presence of morphological and marker-validated atrial (MLC2 A+ cells) and ventricular (MLC2V+ cells) chambers. (F) Vascularization was confirmed by CD31-positive endothelial cell immunolabeling. Image Credit: ACROBiosystems

Characterization of cardiac organoids – functional characterization

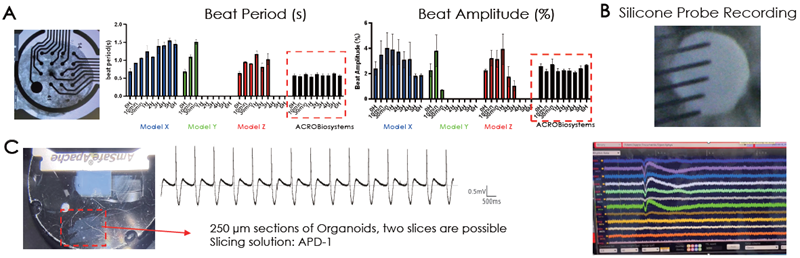

Heart tissue is electrically active. MEA recordings probed electrical activity, demonstrating the cardiac organoid model’s consistent beating periods and amplitudes for up to six hours compared to three different cardiac models (Fig 5A).

Silicon probe recordings, which verified physiological wave complex elements for heart activity (Fig 5B), are another means of assessing extracellular electrical activity. A patch clamp was utilized to verify intracellular electrical activity, and a physiological cardiac waveform was distinguished (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5. (A) Electrical activity of the cardiac organoids was confirmed extracellularly by (A) MEA and (B) silicon probe recordings and intracellularly by (C) patch clamp recordings. The resemblance of a physiological waveform of cardiac beating was identified. Image Credit: ACROBiosystems

Cardiac toxicity and AAV capsid screening modeling on cardiac organoids

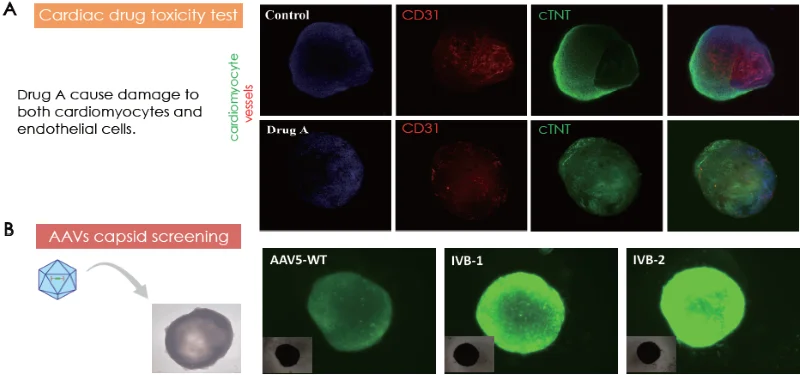

Treating healthy 25-day-old cardiac organoids with proper concentration of drug A (drug name confidential) degrades the cardiomyocytes and the endothelial cells (Fig. 6A). Cardiac organoids cultivated for 11 days were contaminated with AAV5-WT, IVB-1, and IVB-2.

The IVB-2 subtype demonstrated elevated infectiousness and transgene delivery towards cardiac organoids, perceivable through fluorescent intensity from GFP transgene expression.

Figure 6. (A) Cardiac toxicity model by Drug A treatment on cardiac organoids. (B) Cardiac organoids as models for AAV capsid screening. Image Credit: ACROBiosystems

Conclusion

Even after demanding preclinical testing, pharmaceutical drug development has elevated clinical failure rates because of efficacy problems and side effects, potentially due to the absence of relevant and translatable cell models.

Organoids, 3D in vitro tissue models imitating their corresponding organs’ architecture and function, have become promising in drug development and disease modeling to combat elevated rates of clinical drug failure.

Existing organoid strategies typically don’t have some physiological cell types or translatable biological assays. Cerebral organoids have multiple neuronal subtypes and all glial cell types and demonstrate functional activity. Cardiac organoids carry all relevant cell types, are functionally active, and demonstrate mechanical beating.

Alpha-synuclein pre-formed fibril alongside cerebral organoids developed a model of Parkinson’s disease, recapitulating the dopaminergic neuronal degeneration phenotype. Cardiac organoids were degenerated by adding a cardiotoxic drug, in which the cardiomyocyte and endothelial degeneration phenotype could be seen.

The two organoids presented as potential models for AAV screening for gene therapy. Cerebral and cardiac organoids were identified as superior preclinical models for multiple uses, including drug screening and toxicity, gene therapy, and diseases.

References and further reading

- Kim, J., Koo, B.-K. and Knoblich, J.A. (2020). Human organoids: model systems for human biology and medicine. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 21(10), pp.571–584. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41580-020-0259-3.

- Zhao, Z. (2022). Organoids. Nature Reviews Methods Primers, [online] 2(1), pp.1–21. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43586-022-00174-y.

Download Original Poster

Download Original Poster

About ACROBiosystems

ACROBiosystems is a cornerstone enterprise of the pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries. Their mission is to help overcome challenges with innovative tools and solutions from discovery to the clinic. They supply life science tools designed to be used in discovery research and scalable to the clinical phase and beyond. By consistently adapting to new regulatory challenges and guidelines, ACROBiosystems delivers solutions, whether it comes through recombinant proteins, antibodies, assay kits, GMP-grade reagents, or custom services. ACROBiosystems empower scientists and engineers dedicated towards innovation to simplify and accelerate the development of new, better, and more affordable medicine.

Sponsored Content Policy: News-Medical.net publishes articles and related content that may be derived from sources where we have existing commercial relationships, provided such content adds value to the core editorial ethos of News-Medical.Net which is to educate and inform site visitors interested in medical research, science, medical devices and treatments.

Last Updated: Nov 20, 2025