Magnesium: role, deficiency, and sources

How does magnesium influence sleep?

The effect of magnesium supplements and dietary magnesium on sleep

References

Further reading

In modern society, poor sleep quality and sleep deprivation have become a common occurrence that is implicated in several health disorders, such as cardiovascular disease (CVD), obesity, and diabetes.1 Therefore, multiple pharmaceutical and non-pharmaceutical interventions have been formulated to improve sleep quality.

Several studies have indicated an association between sleep and magnesium intake. This article explores the scientific explanations regarding magnesium supplements or dietary magnesium for improving sleep quality.

Magnesium: role, deficiency, and sources

Magnesium is the second most abundant cation in the body that participates in the regulation of numerous biochemical reactions.2 It is a vital cofactor for many enzymatic reactions in our body, particularly those associated with neurotransmitter synthesis and energy metabolism. Magnesium also plays a vital role in vitamin D absorption.3

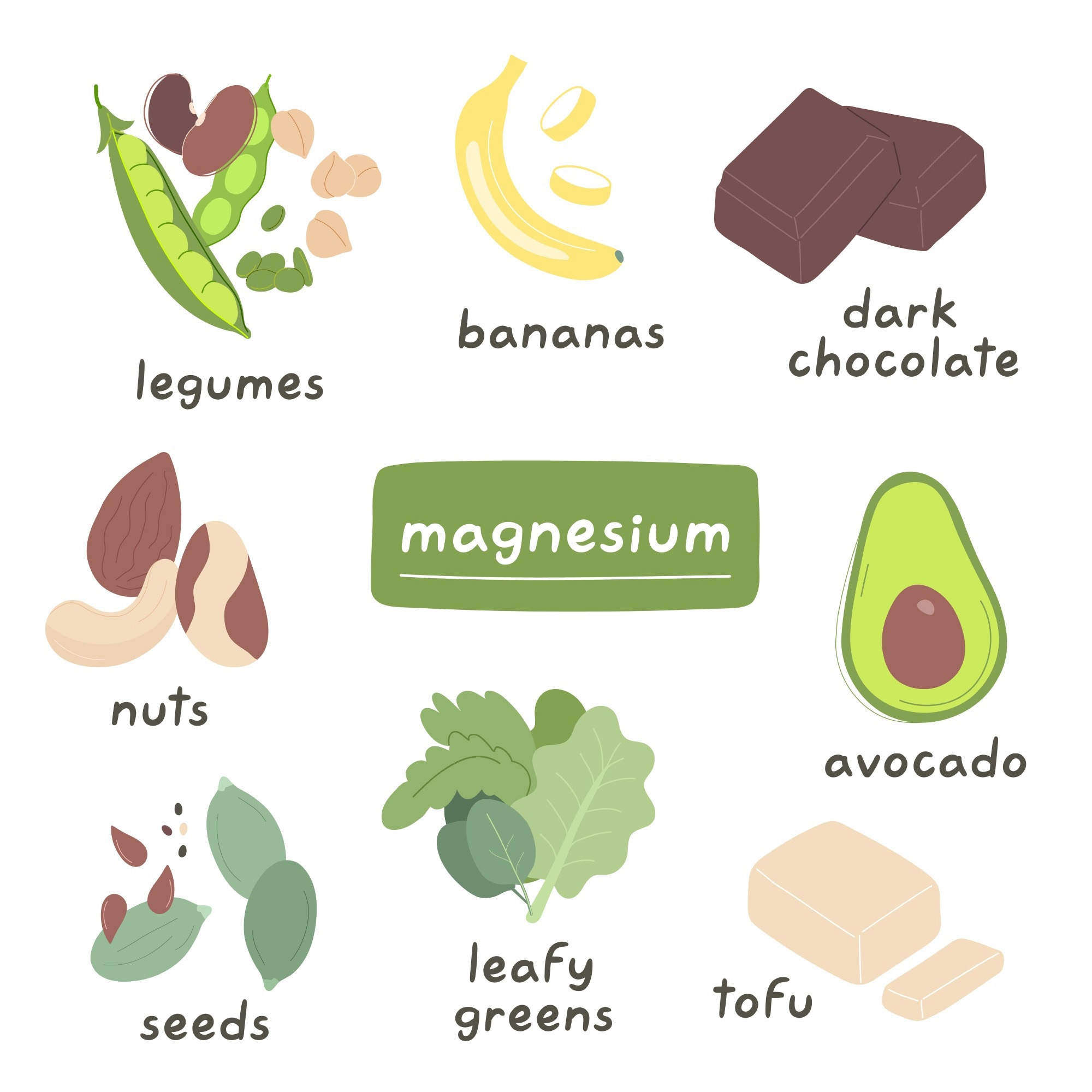

Foods high in magnesium. Image Credit: Innart/Shutterstock.com

Foods high in magnesium. Image Credit: Innart/Shutterstock.com

Magnesium deficiency is linked with aging and inadequate consumption. In the elderly population, the overall decrease in magnesium levels occurs due to a decrease in bone mass, which is a major magnesium source.4

Most studies have shown that magnesium deficiency is attributed to inadequate dietary intake of magnesium due to a lower intake of green leafy vegetables and whole grains and a higher consumption of processed food.

Individuals with alcohol dependence, gastrointestinal illnesses, Crohn’s or celiac disease, parathyroid problems, and type 2 diabetes often exhibit magnesium deficiency.2 Inadequate magnesium level elevates the risk of cardiovascular disease and stroke.5 Individuals with the aforementioned conditions are recommended magnesium supplements.

Food sources rich in magnesium include spinach, avocadoes, and cocoa, particularly dark chocolate. Seeds and nuts, such as peanuts, cashews, sunflower seeds, almonds, hazelnuts, and pumpkin seeds, have high magnesium content.6 Fish and seafood are also rich sources of dietary magnesium.

How does magnesium influence sleep?

Although the exact role of magnesium in sleep regulation is poorly understood, scientists have uncovered several mechanisms through which it could influence sleep.

It is actively involved in regulating central nervous system excitability. Magnesium influences sleep through its involvement in regulating the glutamatergic and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) systems.7 The binding of magnesium to GABA receptors activates GABA, decreasing the nervous system's excitability.

Furthermore, magnesium inhibits the N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor, which induces muscle relaxation through the lowering of intracellular calcium (Ca) concentration in the muscle cells.8

Magnesium plays a vital role in ion channel conductivity, such as NMDA receptor, for absorption, regulates the unilateral entrance of potassium channels, and promotes the binding of monoamines to their receptors. Magnesium also plays an important role in neural transmission at the cellular level, i.e., both the presynaptic membrane and postsynaptic membrane.2

Magnesium may influence sleep duration by regulating the circadian clock.7 Animal model studies have shown that magnesium deficiency reduces the concentration of plasma melatonin, a sleep-promoting hormone.

Existing research has also indicated that magnesium supplementation decreases the concentration of serum cortisol (stress hormone), which calms the central nervous system and potentially improves sleep quality.9

The effect of magnesium supplements and dietary magnesium on sleep

A large-scale cross-sectional study revealed that high magnesium intake is associated with normal hours of sleep. In contrast, lower magnesium intake has been associated with both shorter and longer sleep duration. The optimal magnesium dosage for sleep is dependent on several factors, including age and comorbidity.

According to recent guidelines, 310-360 milligrams/day of magnesium has been recommended for women and 400-420 mg for men. A clinical study indicated that a daily intake of 500 mg of elemental magnesium supplementation for eight weeks increased sleep duration and decreased sleep latency in the older population.10 Pregnant women require 350–360 mg of magnesium per day.

There are different types of magnesium supplements, including magnesium oxide, magnesium citrate, magnesium hydroxide, magnesium gluconate, magnesium chloride, and magnesium aspartate. Each magnesium supplement type has a different absorption rate. Typically, older adults with insomnia are recommended to intake 320–729 mg of magnesium per day from magnesium oxide or magnesium citrate.

Close up magnesium supplements fell out of a glass bottle on a white background. Image Credit: Gala Oleksenko/Shutterstock.com

Close up magnesium supplements fell out of a glass bottle on a white background. Image Credit: Gala Oleksenko/Shutterstock.com

Many studies used the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) as a primary sleep metric to assess the effect of different magnesium supplements, including magnesium oxide, magnesium chloride, magnesium citrate, and magnesium L-aspartate on sleep quality.11

These studies indicated that among all magnesium supplements, the lowest dose of magnesium oxide improved sleep quality. In contrast, magnesium chloride did not exhibit any significant sleep improvement, and magnesium L-aspartate could promote sleep only at a very high concentration of 729 mg.11

It is not necessary to obtain magnesium through supplements only, as it is present in food as well. Regular consumption of foods rich in magnesium can meet the daily requirements. For instance, a 40-year-old non-pregnant woman can meet daily magnesium recommendations by consuming one cup of cooked quinoa, one cup of cooked spinach, and an ounce of almonds.

Before taking magnesium supplements, it is essential to consult a physician because it might interact with other medications, particularly those linked with cancer treatment.

Furthermore, a high dose of magnesium supplements can cause nausea, diarrhea, and cramping in some people. In contrast, higher magnesium consumption from dietary sources is considerably safe because it is digested more slowly and excreted by the kidneys.

References

- Chattu VK, et al. The Global Problem of Insufficient Sleep and Its Serious Public Health Implications. Healthcare (Basel). 2018;7(1):1. doi: 10.3390/healthcare7010001.

- Fiorentini D, et a;. Magnesium: Biochemistry, Nutrition, Detection, and Social Impact of Diseases Linked to Its Deficiency. Nutrients. 2021;13(4):1136. doi: 10.3390/nu13041136.

- Uwitonze AM, Razzaque MS. Role of Magnesium in Vitamin D Activation and Function. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2018;118(3):181-189. doi: 10.7556/jaoa.2018.037.

- Barbagallo M, et al. Magnesium in Aging, Health and Diseases. Nutrients. 2021;13(2):463. doi: 10.3390/nu13020463.

- Rosique-Esteban N, et al. Dietary Magnesium and Cardiovascular Disease: A Review with Emphasis in Epidemiological Studies. Nutrients. 2018;10(2):168. doi: 10.3390/nu10020168.

- Dodevska M, et al. Similarities and differences in the nutritional composition of nuts and seeds in Serbia. Front Nutr. 2022;9:1003125. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.1003125.

- Zhang Y, et al. Association of magnesium intake with sleep duration and sleep quality: findings from the CARDIA study. Sleep. 2022;45(4):zsab276. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsab276.

- Souza AC. Ret al. The Integral Role of Magnesium in Muscle Integrity and Aging: A Comprehensive Review. Nutrients. 2023;15(24):5127. doi: 10.3390/nu15245127.

- Pickering G, et al. Magnesium Status and Stress: The Vicious Circle Concept Revisited. Nutrients. 2020; 12(12):3672. doi.org/10.3390/nu12123672

- Abbasi B, et al. The effect of magnesium supplementation on primary insomnia in elderly: A double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Res Med Sci. 2012;17(12):1161-9.

- Rawji A, et al. Examining the Effects of Supplemental Magnesium on Self-Reported Anxiety and Sleep Quality: A Systematic Review. Cureus. 2024;16(4):e59317. doi: 10.7759/cureus.59317.

Further Reading

Last Updated: Nov 15, 2024