The gastrointestinal (GI) tract begins in the mouth and works its way down the esophagus, through the stomach, both the small and large intestines and the rectum, until it ends at the anus. Bleeding or hemorrhaging anywhere along this pathway may be acute or chronic, and can be due to a host of factors.

Image Credit: PopTika / Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: PopTika / Shutterstock.com

The key symptoms of a GI bleed include hematemesis, or the vomiting of blood, and/ or melena, which is otherwise known as black stool (i.e., blood in stool). Accompanying symptoms may vary, but can include epigastric and diffuse abdominal pain, pale skin, shortness of breath, and alterations of consciousness.

Bleeding within the GI tractis itself not a disease, but rather a symptom of a disease. This bleeding may be divided into upper and lower GI bleeding. The upper GI tract consists of the oral cavity, esophagus, stomach, and the first part of the small intestine, otherwise known as the duodenum. Comparatively, the lower GI tract is comprised of all other parts of the GI tract beginning at the jejunum, or the midsection of the small intestine, to the anus.

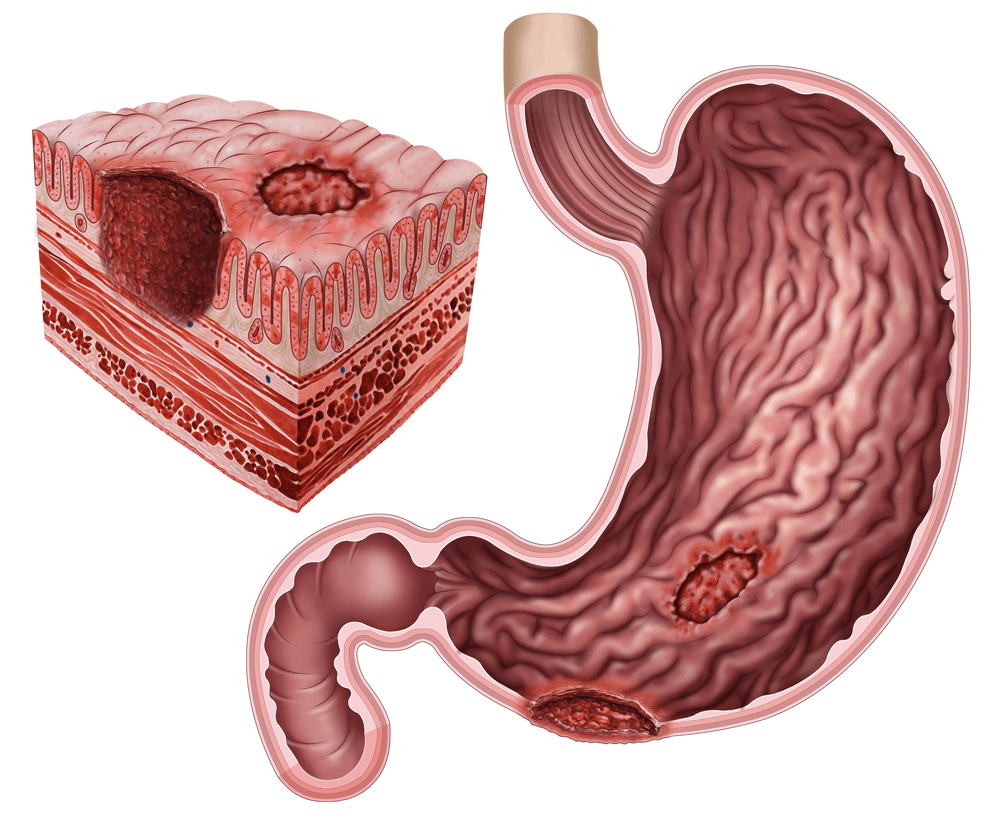

The major causes of an upper GI bleed include esophageal varices, gastritis, peptic ulcers, inflammation, and cancer. The most common conditions associated with a lower GI bleed include diverticulitis, infections, polyps, inflammatory bowel disease, hemorrhoids, anal fissures and cancer.

Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding

Bleeds from the upper GI tract are significant causes of morbidity and mortality and are much more common than lower GI bleeds. Important to note is that the mortality associated with upper GI bleeds are often as a result of comorbidities rather than the actual bleeding itself.

Peptic ulcers are the most common cause of upper GI bleeding. In fact, peptic ulcer disease (PUD) accounts for up to 40% of all case. Those at a particularly high risk for PUD include alcoholics, patients on extensive nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), as well as patients with chronic renal failure.

Image Credit: ilusmedical / Shutterstock.com

PUD has been strongly linked to infection with Helicobacter pylori. This bacterium is responsible for the destruction of protective mechanisms in the stomach and duodenum, which ultimately leads to damage of the organ by stomach acid that would otherwise not be a problem. These ulcers are found more commonly in the duodenum as compared to the stomach; however, both locations present with equal incidences of bleeding.

Esophageal inflammation, erosive esophagitis and erosive gastritis all represent the second most common causes of upper GI bleeding. Acid reflux is considered to be the most common cause of inflammation of the esophagus. Esophageal varices, which are abnormally dilated vessels within the esophagus, are typically seen in patients with portal hypertension and chronic liver disease and these patients are at an increased risk for hemorrhage. In addition to these risk factors, vomiting, due to force, can cause ruptures in the esophagus (Boerhaave syndrome) and resultant upper GI bleeding.

Patients in shock due to trauma, sepsis, or organ failure can also have upper GI bleeds as a result of erosions occurring in the presence of decreased blood flow and altered acidity of the gastric lumen.

Gastrointestinal Bleed

Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding

Lower GI bleeds account for up to one-third of all GI hemorrhages and are frequent causes of admission to the hospital due to their association with increased morbidity and mortality. Bleeding in this segment of the GI tract may be classified into 3 categories, which include massive bleeding, moderate bleeding, and occult bleeding.

As implied, massive bleeding is a potentially life-threatening condition that requires an immediate blood transfusion. Occult bleeding is seen most often with colorectal cancer; these patients typically present with iron deficiency anemia.

Approximately 6 in every 10 lower GI bleeds are due to diverticular disease, which includes diverticulitis of the small intestine and of the colon. Constipation, a lack of fiber in the diet, advancing age, and the use of drugs such as aspirin and NSAIDs are all risk factors for diverticular disease.

Small vascular malformation of the GI tract, otherwise known as angiodysplasia, often occurs in the ascending colon. Angiodysplasia can be associated with certain conditions such as chronic renal failure, and also increases the patient's risk of hemorrhage. However, a GI bleed due to angiodysplasia is often less intense when compared to those that result from diverticular disease, as the bleeding in angiodysplasia is from veins and/ or capillaries.

Inflammatory bowel diseases, such as Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis, and non-infectious gastroenteritis account for just over a tenth of lower GI hemorrhages, whereas neoplasms and benign anorectal diseases such as hemorrhoids and anal fissures account for up to 20%.

These health conditions typically cause bleeding as a result of the destruction of the bowel mucosa. Some bacterial GI infections can also cause hemorrhaging through the same mechanism. Other causes of lower GI bleeds include opportunistic infections associated with HIV, such as lymphoma, CMV-colitis, and Kaposi sarcoma.

References

Further Reading

Last Updated: Mar 17, 2021