Clostridium difficile: a highly successful human gut pathogen

Challenges in managing clostridium difficile infection

C. difficile as a ubiquitous microorganism

Faecal microbiota transplant and C. difficile

References

Further reading

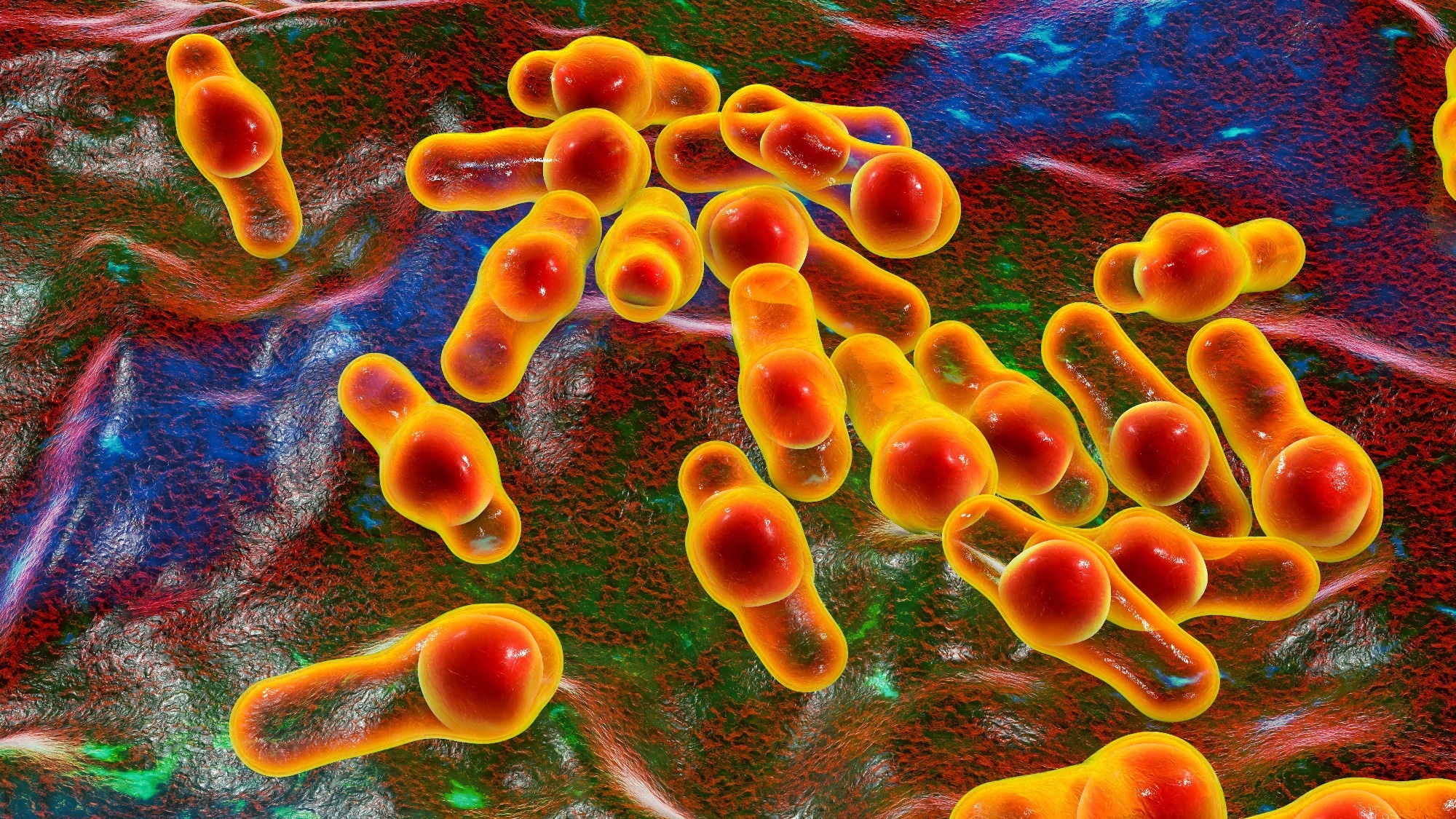

Clostridium difficile is an unpleasant, sometimes severe, and potentially lethal infection. It is an enteric pathogen whose armory involves the production of a toxin leading to gut dysphoria and symptoms of diarrhea.

The pathogen commonly occurs in patients on antibiotic treatment and in those in hospitals where the risk of an outbreak is high due to the rapid means by which this pathogen can spread. This makes C. difficile particularly dangerous and challenging to manage.

Image Credit: KaterynaKon/Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: KaterynaKon/Shutterstock.com

Clostridium difficile: a highly successful human gut pathogen

Clostridium difficile –– now called Clostridioides difficile ––is a Gram-positive spore-forming bacteria and part of the normal gut microflora in humans.

Its harmful effects occur mainly in vulnerable groups, such as the elderly, those with a compromised immune system, those who have undergone antibiotic treatment, and those who have been in a healthcare setting ––a hospital or a care home ––for a long period. In fact, in the Western world C. difficile is amongst the most common causes of hospital-acquired infective diarrhea.

When competing gut microorganisms are killed by antibiotic use, C. difficile can cause antibiotic-associated diarrhea (ADD). Following ADD, pseudomembranous enterocolitis can lead to generalized inflammation of the colon. So, what makes C. difficile so successful as a pathogen?

C. difficile has developed unique survival mechanisms that facilitate its successful proliferation in the competitive gut environment. The remarkable adaptability of this pathogen occurs in large part due to the diversity of its genome.

When C. difficile encounters cellular stress, it can invoke two strategies for survival, to-wit: 1. the production of a toxin ––this is responsible for the onset of diarrhea in the human host, and 2. formation of a protective coat through sporulation to either aid its persistence in the gut or else facilitate an escape.

Clostridium difficile (c.diff) Infection | Clostridioides difficile infection | GI Society

Challenges in managing clostridium difficile infection

Transmission of Clostridium difficile occurs via the spores mentioned above that are resistant to commonly implemented sanitization measures, such as hand sanitizer gels and disinfectants.

A current or recent stay in the hospital poses a risk of exposure to a C. difficile infection. Here the risk for symptomatic and asymptomatic exposure is much higher than in the community.

While infection control measures generally focus on symptomatic individuals because these cases are more contagious, a need for asymptomatic surveillance has been reported.

This is because these patients can contribute to transmission rates, too, though their relative contribution is more difficult to determine. It has been reported to be quite high.

Kong et al. (2015) recently conducted a large-scale study investigating the relative roles of symptomatic and asymptomatic carriers responsible for a large measure of transmission within the hospital setting. Here they sequenced the genomes of over 500 C. difficile isolates obtained from patients comprising both groups to assess the rate of spread.

The outcome gave no conclusive answer to the problem: it was difficult to determine whether wither symptomatic or asymptomatic cases led to a higher incidence of transmission.

Another challenge in managing C. difficile is that although antibiotics are good for treating the first infection, the subsequent infection may no longer respond to treatment in some patients. This can result in lowered quality of life and, in some cases, death. A causal link between the use of third-generation antibiotics like cephalosporin and C. difficile has been established, as has the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics per se.

C. difficile as a ubiquitous microorganism

Human health is interconnected with that of animals and the environment. The spores of C. difficile are commonly found in the soil. Certain C. difficile have been well-reported in animals, such as bats, dogs, and horses.

Food animals are a major reservoir and amplification host for C. difficile. Cephalosporin has been widely used in animals since it was first licensed in the US in 1990.

In the 21st century, whole genome sequencing (WGS) and high-resolution typing have revealed that C. difficile from humans, animals, food, and the environment are closely related, suggestive of zoonoses and/or/or anthroponoses.

Consequently, Lim et al. (2020) report that contaminated food and the environment are conduits for transmission between animals and humans. C. difficile is intrinsically resistant to broad-spectrum antibiotics and cephalosporin. So, what can be done to manage the treatment C. difficile infection without resorting to these medicines?

Faecal microbiota transplant and C. difficile

Fecal microbiota transplant (FMT) has successfully treated C. difficile. Since this treatment was first approved in 2013, FMT has proven effective in around 90% of patients ––a significant stride in progress compared to antibiotic treatment, which works in only around 20-40% of cases and is far more expensive.

Healthy stool donations are processed in a sterile laboratory for fecal transplant into the gut via a nasogastric tube or colonoscopy. The sample can be frozen for up to six months at –80 °C. This recently licensed medicine offers much hope for patients in the battle against C. difficile.

References

Further Reading

Last Updated: Jun 20, 2023