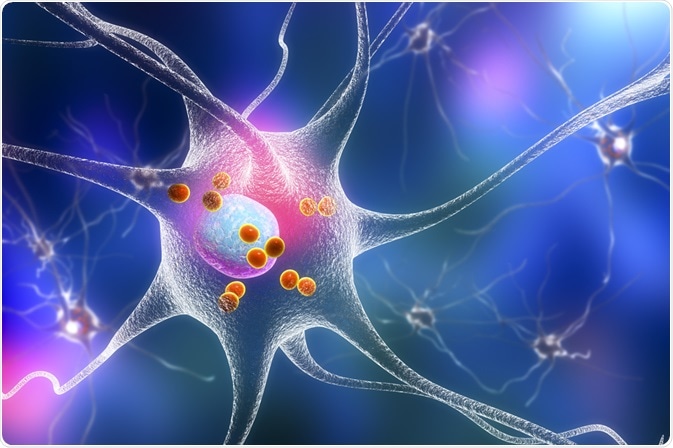

Parkinson’s disease is a neurodegenerative disorder clinically characterized by dyskinesia (impairment of movement), resting tremor, bradykinesia (slow movements), dystonia (stiffness of muscles including facial muscles), a stooped posture, drooling, sexual and urinary dysfunction, and in some cases psychiatric symptoms including psychosis, dementia, and depression.

Image Credit: Kateryna Kon / Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: Kateryna Kon / Shutterstock.com

Parkinson’s is also more prevalent in men than in women by a 3:2 ratio. At the heart of Parkinson’s disease pathology, dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra (striatum) progressively degenerate over time to cause the symptoms.

Estrogen and the Nigrostriatal Dopaminergic System

Because Parkinson’s disease is 50% more prevalent in men than women and because some dopaminergic drugs used to treat Parkinson’s disease affect men and women differently, it is thought that estrogen may be protective in Parkinson’s disease.

It is known that estrogen can bind to receptors within cells in the striatum to regulate gene expression; however, the mechanisms by which estrogen is able to do this are still poorly understood, as the effects are thought to be through non-genomic mechanisms.

Studies have shown that estrogen can modulate nigrostriatal dopamine synthesis and subsequent release. Intraperitoneally-administered estrogen in mice leads to rapid increases in dopamine synthesis from within nigrostriatal axon terminals.

Furthermore, estrogen is able to release dopamine immediately without depleting dopamine in rats. It has also been observed that dopaminergic activity is highest during oestrus following a surge in estrogen.

Cellular and animal studies

Studies using cultures of neurons incubated with estrogen found that neurons were resistant to apoptosis (cell death) induced by bleomycin sulfate.

Proof that estrogen was protecting neurons from injury was due to the apoptosis occurring after specifically blocking the estrogen receptor with an antagonist. Subjecting cultured neurons to estrogen pre-incubation also prevented glutamate-mediated neurotoxicity, a common mechanism of neuronal death.

Animal models of Parkinson’s typically use MPTP or 6-OHDA to induce selective nigral dopaminergic neuronal death. Estrogen has been shown to promote neuronal survival in such models of Parkinson’s, thought to be due to estrogen's ability to interfere with dopamine binding for reuptake at presynaptic sites.

As such, estrogen is able to confer protective properties to dopaminergic neurons by altering the levels of dopamine recycling. 6-OHDA also selectively kills dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra, but pre-treatment with estrogen via time-release capsules has demonstrated protection with subsequently lower dopamine depletion.

Another key mechanism by which neurons selectively die in a variety of neurodegenerative diseases is that of oxidative stress. It has been demonstrated that estrogen can protect neurons with its antioxidant effects. Estrogen is able to significantly reduce the formation of toxic hydrogen peroxide and nitric oxide free radicals in cultured neurons.

Clinical studies

Recent clinical studies have shown the beneficial effect of estrogen on Parkinson’s disease prognosis. One study investigated 40 postmenopausal women with Parkinson’s disease, of which 20 received 0.6mg estrogen, and the other 20 received a placebo over an 8-week period.

Motor function was significantly improved in the group receiving estrogen. Motor scores improved by 3.5 points for the estrogen group compared to less than 0.4 points for the placebo group.

In a small study of 8 postmenopausal women with Parkinson’s, women received either 0.1mg/kg estrogen or a placebo for ten days. Their medication was withdrawn, and they were infused with L-DOPA.

In this study, the threshold dose of L-DOPA needed to provide a beneficial effect was reduced in the group taking estrogen, but they showed no significant improvement in symptoms. This study, however, only looked at the effect for ten days compared to eight weeks in the previous study, and may suggest that estrogen confers longer-lasting effects that take time to initiate.

Other studies have shown the beneficial effect of estrogen on the cognitive symptoms associated with Parkinson’s and dementia, which is commonly comorbid with Parkinson’s. A study looking at over 10000 elderly patients found that patients diagnosed with Parkinson’s regularly using estrogen has significantly less cognitive impairment than those who did not use estrogen.

However, this was an observational study and not a randomized controlled study; therefore, other factors may have contributed to this effect.

So far, all of the estrogen work has been studies in females and may explain the sex differences in onset and prevalence of Parkinson’s in women compared to men. Using a mouse model of Parkinson’s, researchers investigated the effects of brain-selective estrogen therapy on the pathology of Parkinson’s mice. Male mice developed Parkinson’s much quicker than female mice.

The reason for this was that the females displayed a higher alpha-synuclein tetramer to monomer ratio. Brain-selective estrogen treatment in male mice led to the same increase in alpha-synuclein tetramer to monomer ratio and was associated with amelioration of Parkinsonian pathology by increasing autophagy of monomers.

In summary, estrogen seems to have a neuroprotective effect against dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra. The effects of this may only be mild to moderate and be pertinent to only some of the symptoms of Parkinson’s (such as the non-motor symptoms) but may prove beneficial in combination with other medications, such as L-DOPA.

The mechanisms underlying these effects still need to be properly investigated before the development of estrogen-based treatments in women and in men with Parkinson’s. However, estrogen may eventually serve a role in the prevention and treatment of Parkinson’s disease.

Further Reading

Last Updated: Apr 4, 2020