Rabies is a zoonotic disease, spread from animals to humans. Though dogs are the main disease carriers, they are by no means the only ones, with wild bats, foxes, and many other wild animals also being capable of readily transmitting the virus.

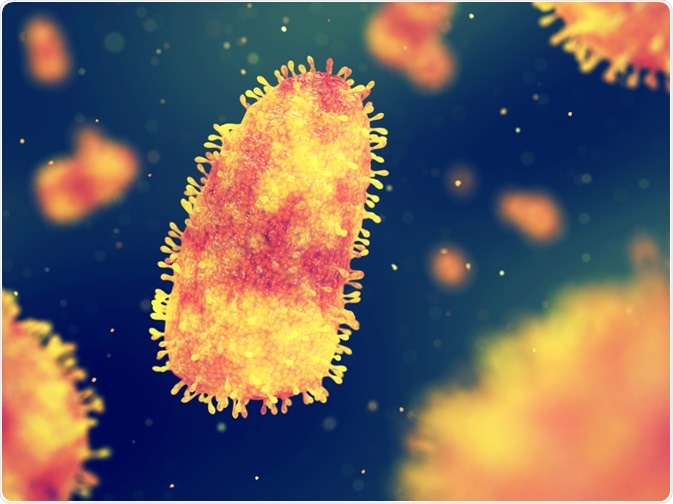

Image Credit: nobeastsofierce/Shutterstock.com

Rabies is described as a Neglected Tropical Disease (NTD) that occurs mostly among poor populations in remote rural areas since these make up 80% of the total. Death in these areas as a result of rabies is common, unlike in the developed world.

Prevention of rabies after a potentially infected bite begins with the immediate and thorough washing of the wound with soap and water. It is impossible to overstress the importance of this seemingly minor step, which all at-risk populations should be educated about.

Symptoms of rabies

The incubation period may vary from a week to even a year, though these are extremes. In the majority of cases, following a bite with the introduction of the virus into the host body through infected saliva, the virus typically incubates in the body for up to three months before clinical manifestations of rabies occur.

The rabies virus first replicates at low levels, in the skeletal muscle or connective tissue near the site of the bite, before it gains entry to the neuromuscular junction and enters the peripheral nerve. The proximity of the bite to the brain, and the viral load in the saliva, may account for this difference in the incubation period.

The earliest symptoms may include fever and neurological symptoms like pain, tingling, pricking, or burning (clubbed together as paresthesias) at the wound site, without obvious cause. Intense itching at the site has also been reported quite often.

These are probably due to the spread of the virus through the peripheral nerve trunks, in a retrograde manner, towards the central nervous system (CNS). Once it reaches the spinal cord, and then the brain, it causes severe and progressive excitation of the nerve cells, typically causing death.

Different presentations

Rabies is known to occur in two forms, the furious and the paralytic form. In the first, comprising approximately 80% of human rabies cases, the onset is signaled by hyperactivity, hydrophobia, and severe or uncontrollable excitability.

These are the signs of encephalitis. The patients may be extremely restless, agitated, thrash about, bite, hallucinate or experience severe confusion, with very abnormal behavior.

The characteristic hydrophobia, extreme or irrational fear of water, especially as a symptom of rabies, and in some patients, aerophobia, or fear of drafts or fresh air, occur during this phase. The reason for these very distressing symptoms is that the patient experiences spasms of the throat and larynx when the virus affects the brain areas controlling speaking and swallowing, as well as breathing.

A breath of wind, or an attempt to swallow a sip of water, may bring on the spasms, which is why the patient develops an aversion to water. The foaming at the mouth that is often reported is due to the same inability to swallow saliva, coupled with the excessive production of saliva.

This phase may last for hours or days, after which they begin to have episodes of excitability rather than constant agitation. In between the episodes, they are calm, cooperative, and clear-headed. The “furious” episodes last for five minutes or less at a time.

Such episodes may come on as a result of some stimuli, whether something the patients see, hear or touch, but in other cases, no obvious trigger can be identified. Some patients also have seizures. Finally, death ensues as a result of cardiorespiratory failure, in most cases, while some patients go into a paralytic stage.

Death may also be due to simple exhaustion, seizures, or extensive paralysis.

The paralytic form, also known as dumb or apathetic rabies, makes up one in five cases. The patient is characteristically quiet and lucid throughout. The course of the illness is a little more prolonged, beginning with tingling or paralysis of the bitten limb.

The patients often complain of headaches and fever at first. The paralysis is flaccid in nature, beginning with the muscles nearest the wound, and extending upwards to cause quadriplegia. For this reason, dumb rabies may lead to misdiagnosis as the post-viral autoimmune polyneuropathy called Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS).

Finally, the patient lapses into a coma after about ten days, which ends in death after a variable period, depending on the level of care. Death is due to respiratory weakening and arrest of breathing.

What underlies these symptoms?

Scientists have not succeeded in uncovering the mechanisms that lead to the difference in clinical presentation in rabies. Some have suggested that the type of animal vector, the site of the wound, the incubation period, or a history of prior rabies vaccination, may be responsible, but the proof is still awaited.

No distinctive differences have been identified in the genetic profile of the rabies viruses isolated from these two types of presentations. In all cases, the brainstem and the spinal cord were the main sites of the infection.

In furious rabies, the anterior horn of the spinal cord appears to be perturbed in its function, with progressive focal denervation beginning at the site of the bite. This is obvious even when the sensory function remains normal and there is no evidence of any clinical weakness of the muscles. The proximal motor neurons also appear to be functioning normally.

In paralytic rabies, peripheral nerves are affected by demyelination, accounting for the weakness. While immune cells against the virus have not been found, nor does the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) show rabies neutralizing antibodies, an immune hypothesis cannot yet be ruled out. For instance, abnormal immune responses to the peripheral nerve antigen may be involved in the etiopathogenesis of this paralytic disease. Notably, demyelination may be seen in Guillain-Barre syndrome, which is an important differential diagnosis.

The spinal nerve roots were intensely inflamed, especially in the segment of the spinal cord supplying the bite location. However, the inflammation was more marked in paralytic rabies compared to furious rabies.

Only patients with furious rabies showed central chromatolysis in the anterior horn cells – “swelling of the neuronal cell body, disruption and dispersal of Nissl granules from the central part of the perikaryon and peripheral displacement of the nucleus, classically seen in response to axonal injury and which may also be seen in rabies.”

Conclusion

While the current state of knowledge is inadequate to differentiate the pathophysiology of these types of rabies, highly effective interventions are available to prevent both types, including wound care, rabies immunoglobulin, and PEP. This knowledge, and the resources necessary to implement it, should be disseminated to all parts of the world to prevent this highly avoidable disease, along with sanitary measures to curb transmission from animals to humans.

References:

Last Updated: Feb 3, 2022