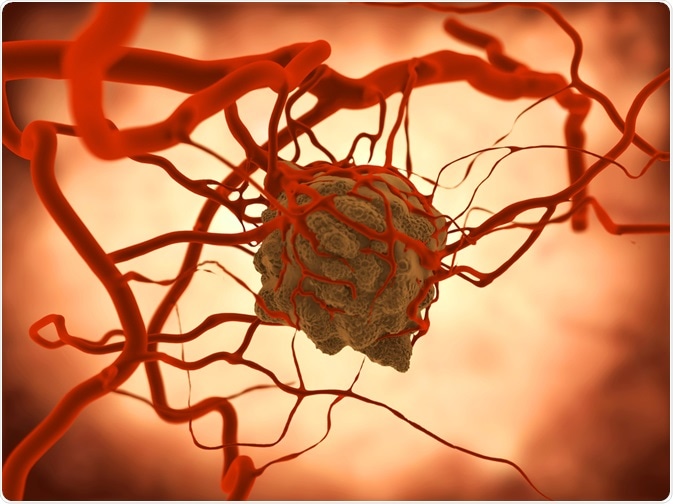

Cancerous tumor cells are characterized by their rapid rate of cell division, which is no longer controlled as it is in normal tissues. Somatic cells of the body normally undergo a resting period during the G0 phase of mitosis and differentiate into functional cells that are no longer capable to divide.

Image Credit: Juan Gaertner / Shutterstock.com

In the case of active tumors, cells are activated by specific kinases, which are enzymes that add phosphate groups to other molecules, and enter a phase of relentless proliferation. Such cells typically display abnormalities in the mechanisms that regulate normal cell division, differentiation, and survival.

In order to accommodate these changes, malignant cells show signs of morphological and cytoskeletal alterations. Prevention of such restructuring and subsequent cell division is a key mechanism of the drug paclitaxel, which makes it an effective treatment for aggressive cancers.

Affecting the function of microtubules

In general, structural proteins do not represent important drug targets. One of the exceptions is a protein named tubulin, which is a heterodimer formed by alpha and beta subunits with 40% sequence identity and virtually identical three-dimensional structures.

Tubulin polymerizes into small tubes called microtubules, which are responsible for mitosis, cell movements, preservation of cell shape, signal transmission, as well as the intracellular trafficking of organelles and macromolecules. Microtubules arise from the specific longitudinal self-assembly of tubulin dimers to form protofilaments, which interact to constitute the wall of these structures.

Paclitaxel stabilizes microtubules and reduces their dynamicity, promoting mitotic halt and cell death. Unlike other drugs that act on microtubules and induce the disassembly of microtubules, as is the case with vinca alkaloids, paclitaxel boosts the polymerization of tubulin and overproduction of microtubules. Moreover, this drug binds to the N-terminal 31 amino acids of the beta-tubulin subunit in the microtubule.

Therefore, microtubules that are formed under the influence of paclitaxel are exceptionally unstable and dysfunctional, causing the death of the cell via disruption of the normal microtubule dynamics and vital interphase processes. Simply put, an affected cell can no longer use its own cytoskeleton in a flexible manner.

Other modes of action

Further research has shown that paclitaxel drug plays a vital role by binding to an anti-apoptotic agent that prevents cell death, B-cell Lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2), and stopping its function. The drug attacks the serine residues at sites 70 and 87 while they act on microtubules; therefore, being a tubule poison, this drug can also kill cancer cells that express Bcl-2.

Paclitaxel also induces the expression of the genes for tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin 1 (IL-1), as well as several other inducible genes in macrophages. This causes a reduction in the surface expression of TNF-α receptors as well. Such properties add significantly to the antitumor efficacy of paclitaxel.

In addition to this main mode of action as a microtubule stabilizer, paclitaxel may also act as a molecular mop by sequestering free tubulin, thus effectively depleting the cell’s supply of tubulin monomers and dimers. This activity can also trigger apoptosis, which is a process that is also known programmed cell death.

Mechanisms of acquired resistance

The efficacy of paclitaxel is significantly limited by the development of acquired resistance. Two principal mechanisms of resistance have been described for this drug. Some tumors are known to contain tubulin subunits with a reduced ability to polymerize into microtubules and an inherently slow rate of microtubule assemblage, which can be normalized by paclitaxel and other taxanes.

In the second mechanism, membrane phosphoglycoproteins that function as drug-efflux pumps are amplified. The multidrug-resistant phenotype of tumor cells can result in varying degrees of cross-resistance to natural products with bulky structures, i.e., a group of drugs where paclitaxel can be found as well.

Recent research has shown that an increased expression of tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced protein 1 (TNFAIP1) results in acquired resistance to paclitaxel. TNFAIP1 competes with paclitaxel for binding to beta-tubulin, preventing in turn tubulin polymerization, cell cycle arrest and ultimate cell death.

References

Further Reading

Last Updated: May 13, 2023