The innate/general resistance system and the adaptive system are the two main subsystems of the immune system. To generate an efficient immune response, the innate and adaptive systems constantly interact with one another.

The innate immune system, also known as general resistance, consists of several defensive mechanisms that are constantly active and serve as the first line of defense against pathogenic substances. These responses, however, are not limited to a single pathogenic agent. Innate immune cells are selective for conserved molecular patterns seen on all microorganisms.

In contrast to the innate immune system, the adaptive immune system's responses are tailored to the specific pathogen. This response will take longer than the natural response to manifest.

Adaptive immunity contains specialized immune cells and antibodies that target and eliminate foreign invaders while also remembering what those substances look like and creating a new immune response to prevent sickness in the future. Adaptive immunity can last a few weeks or months, or it might endure a long period, even for the rest of a person's life.

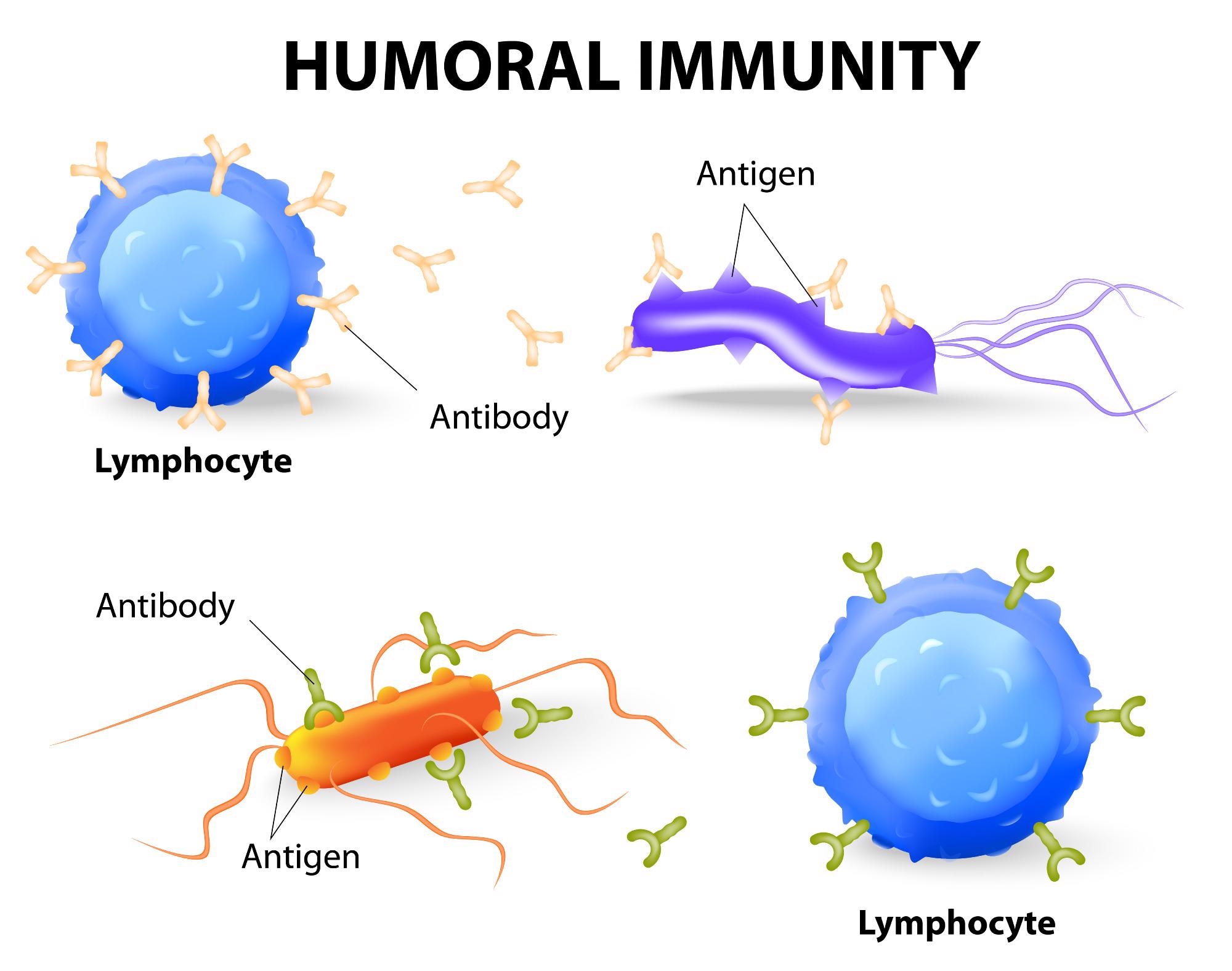

Humoral immunity and cell-mediated immunity are two forms of adaptive immune responses that allow the human body to protect itself against dangerous agents including bacteria, viruses, and poisons, in a targeted manner. While there is some overlap between these immune response arms - both rely on lymphoid cell functions - there are also some significant differences.

Image Credit: Designua/Shutterstock.com

Humoral immunity

When foreign material - antigens - is recognized in the body, the body responds with an antibody-mediated reaction. Extracellular intruders, such as bacteria, are commonly found in this foreign material. B cell lymphocytes, a type of immune cell that makes antibodies after detecting a specific antigen, are principally responsible for this method.

Lymphocytes known as naive B cells circulate throughout the body via the lymphatic system. These cells produce antigen-specific molecules that are necessary for detecting infectious pathogens in the human body. When naive B cells in the lymphatic system come into contact with an antigen, they begin the differentiation process that results in the formation of memory B cells and effector B cells.

Memory B cells and effector B cells produce the same antigen-specific molecules as their parent naive B cell during this development. The activated memory B cells express these antigen-specific molecules on their surface with the help of T cell lymphocytes, which are activated by MHC class II receptors that recognize microbial-associated antigens. The effector B cells secrete these molecules in the blood to bind the antigen of interest.

Cell-mediated immunity

Cell-mediated immunity, unlike humoral immunity, does not rely on antibodies to perform adaptive immunological activities. Mature T cells, macrophages, and the production of cytokines in response to an antigen are the main drivers of cell-mediated immunity.

To recognize intracellular target antigens, T cells that participate in cell-mediated immunity rely on antigen-presenting cells that have membrane-bound MHC class I proteins. The maturation and differentiation of naive T cells into helper or killer T cells are dependent on the binding specificity of MHC proteins to external antigens.

Cell-mediated immunity is activated when cells in the body are infected by a virus, bacterium, or fungus (intracellular invaders). T lymphocytes can detect malignant cells with the help of MHC class I proteins. Helper T cells, killer T cells, and macrophages are the three main kinds of lymphocytes involved in cell-mediated immunity.

When a "helper" T cell encounters an antigen-presenting cell in the body, it releases cytokines, which are signaling proteins. These cytokines cause "killer" T lymphocytes and macrophages to flock to the antigen-presenting cell in an attempt to eliminate it.

Humoral vs cell-mediated

B cells activate humoral immunity, whereas T cells activate cell-mediated immunity. The major difference between humoral and cell-mediated immunity is that humoral immunity produces antigen-specific antibodies, whereas cell-mediated immunity does not. T lymphocytes, on the other hand, kill infected cells by triggering apoptosis.

Humoral immunity develops quickly, whereas cell-mediated immunity takes longer. Extracellular microorganisms and their poisons are targeted by humoral immunity. Intracellular microorganisms (such as bacteria) and tumor cells are targets of cell-mediated immunity.

The Ig, CD40, CD21, and Fc receptors are the humoral immunity's accessory receptors. The accessory receptors of cell-mediated immunity are CD2, CD3, CD4, CD8, CD28, and integrins. Humoral immunity recognizes the unprocessed antigens. In humoral immunity, plasma B cells release antibodies. Cytokines are released by T-cells. Tumor cells and transplants are immune to humoral immunity. Tumor cells and transplants are both affected by cell-mediated immunity.

Significance of humoral and cell-mediated immune response

T-cell responses, which are part of cell-mediated immunity, play a vital role in controlling viral infections. T-cells do this through developing effector activities such as the generation of chemokines and cytokines, which can have direct and indirect antiviral effects, as well as assisting in the overall immune response regulation.

Certain effector T-cells can kill virus-infected cells via cell-to-cell contact, providing an important mechanism of killing the host's cells, which serve as offspring virus generation sites. Immune responses mediated by cells are not only beneficial during the acute phase of viral infections, but they also help to create long-term immunological memory.

Humoral immunity is extremely important in both health and disease, and it can be both useful and harmful. Antibody-mediated protection against pathogens induced by vaccines or infections is crucial in host defense, but pathogen-specific antibodies can also promote infectious processes or drive pathology. Loss of immunological tolerance is linked to the generation of self-reactive antibodies, which can aggravate the condition, and loss of growth control can lead to a variety of B cell malignancies.

For these and other reasons, researchers must continue to investigate how humoral immunity is regulated.

References:

- Dornell, J. (2021). Humoral vs Cell-mediated Immunity. [online] Technology Networks (Immunology and Microbiology). Available at: https://www.technologynetworks.com/immunology/articles/humoral-vs-cell-mediated-immunity-344829

- Pampuria, P., and Lang, L., M. (2018). Regulation of Humoral Immunity by CD1d-Restricted Natural Killer T Cells (Chapter-5). Immunology (Academic Press), pp 55-73. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-809819-6.00005-8.

- Panawala, L. (2017). Difference Between Humoral and Cell Mediated Immunity.

- Zajac, A., J. and Harrington, L., E. (2014). Immune Response to Viruses: Cell-Mediated Immunity. Reference Module in Biomedical Sciences, Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-801238-3.02604-0.

- Adaptive Immunity. [online] National Cancer Institute (NIH). Available at: https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/adaptive-immunity

- Clem A. S. (2011). Fundamentals of vaccine immunology. Journal of global infectious diseases, 3(1), 73–78. https://doi.org/10.4103/0974-777X.77299

Further Reading

Last Updated: Jan 7, 2022