Microsporidosis represents an infection with the spore-forming, obligate intracellular protists. Patients suffering from infections with microsporidia are prone to developing enteritis, keratoconjunctivitis and disseminated diseases that involve muscles and other organs.

These curious microorganisms have not been studied thoroughly as disease agents due to their small size, poor staining properties and the need for electron microscopy for diagnosis.

Microsporidiosis was seldom described in humans until the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) pandemic began in the early 1980s. As the researchers gathered more and more information on microsporidians (especially after employing evolving molecular tools), it became obvious that host immunity plays a pivotal role in disease development and dominant clinical manifestations. However, there are still a lot of question marks, as the bulk of data was derived from animal models.

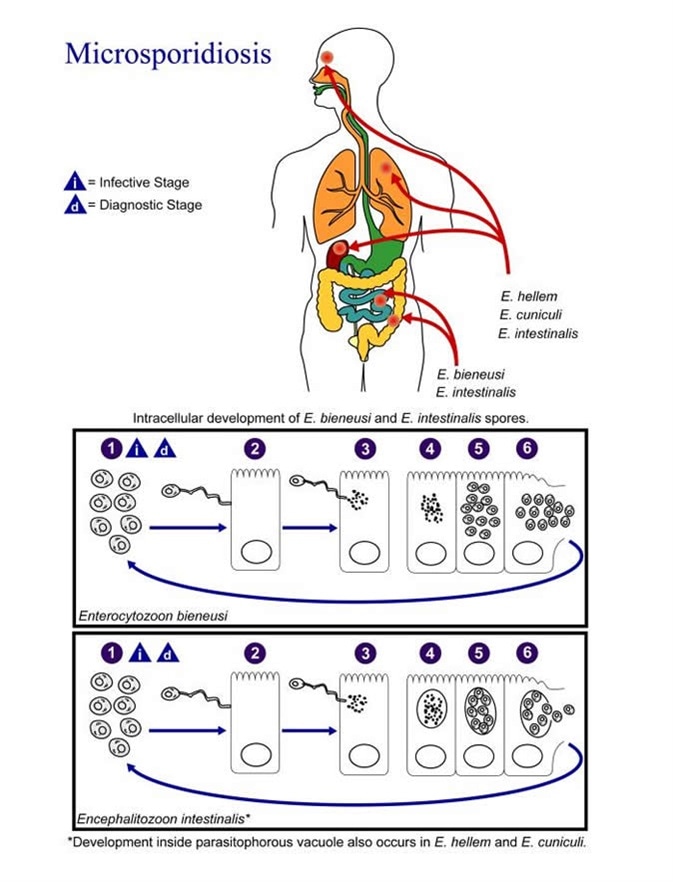

Illustration of the life cycle of the agents responsible for causing Microsporidiosis. Image Credit: CDC/Alexander J. da Silva, PhD/Melanie Moser

Microsporidiosis in Immunologically Competent Hosts

In immunologically competent hosts, microsporidiosis initially undergoes an acute phase when clinical signs of the disease may be discernible (one example is transient accumulation of fluid in the abdomen). This is followed by a chronic phase of the disease with barely a few evident clinical manifestations, but with persistent microsporidian infection.

Since mice are natural hosts of Encephalitozoon cuniculi species, and the organisms disseminate following the same route as in infected humans, euthymic murine models are considered particularly useful to mimic life cycles of microsporidia in immunocompetent hosts.

Using these models, the continued expression of specific antibodies, sporadic shedding of the organisms and the observation of microsporidia-associated lesions in necropsy demonstrated that persistent microsporidial infections are indeed common. There is also evidence of the role of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species, iron sequestration, as well as innate immune responses potentiated by macrophages.

However, it is not completely clear whether immunocompetent humans develop chronic microsporidiosis or the infection clears eventually, with serologic studies supporting the former possibility. What we know is that interactions between host and microsporidial pathogen manifest across different layers of host biology – from transcriptional genomic changes in the genome to potential alterations in the behavior of the host.

Microsporidiosis in Immunologically Deficient Hosts

Among humans, microsporidiosis was initially recognized in children with impaired function of the immune system. Then the infections with this group of microorganisms were increasingly recognized during the AIDS pandemic – most notably in individuals with less than 100 CD4-positive T-lymphocyte cells per microliter of blood.

When the aforementioned Encephalitozoon cuniculi species was introduced to immunodeficient athymic mice (without functional T lymphocytes), or mice with severe combined immune deficiency (without functional T and B lymphocytes), a rapid development of grave ascites and death have been observed. Likewise, severe clinical manifestations were seen in SIV-infected rhesus monkeys with compromised immune systems that were infected either with Encephalitozoon cuniculi, Encephalitozoon hellem or Encephalitozoon intestinalis.

Furthermore, microsporidian infections located in immunologically privileged locations may result in clinically significant disease as well. If the lens or cornea of the eye are affected, there may even be a progression towards spontaneous rupture of the lens or corneal ulcers, respectively.

In conclusion, microsporidia may not lead to an inflammatory response in the affected tissues, but they often do elicit granulomatous inflammation with accompanying infiltrate of mononuclear cells. Also, it is not known whether microsporidiosis in immunocompromised hosts represents activation of a latent infection, or infection is acquired 'de novo'.

Further Reading

Last Updated: Feb 27, 2019