Natural killer (NK) cells are large granular lymphocytes. They possess natural cytotoxicity against tumor cells and virus-infected cells, and they produce cytokines.

NK cells are part of innate immunity, and thus are intrinsically able to differentiate target cells from healthy cells that carry self-antigens. This differentiation occurs through the use of several cell surface receptors, some of which activate and some of which inhibit its activity.

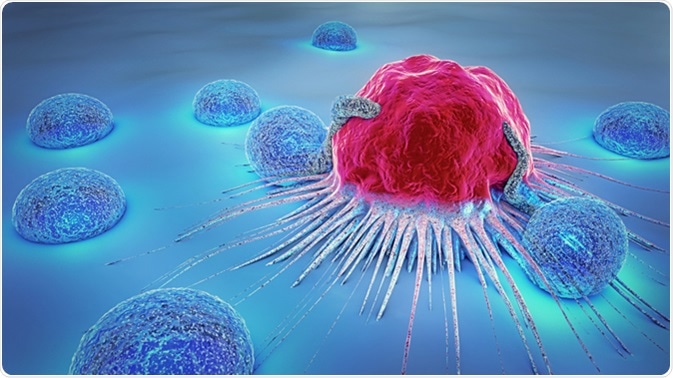

3d illustration of a cancer cell and lymphocyte. Image Credit: Christoph Burgstedt

NK Cell Actions

The activating NK cell receptors lead to the recognition of cell surface ligands that appear on cells which are under attack in some way. This may include the self-ligands induced by stress, non-self ligands induced by infection, and Toll-like receptor (TLR) ligands.

For instance, when NK cells come into contact with TLR ligands, the result is increased cytotoxicity and decreased production of interferon-gamma. Another receptor is the Fc receptor CD16 which promotes the recognition of target cells which are coated with antibody to cause antibody-dependent cell cytotoxicity (ADCC).

Inhibitory receptors, on the other hand, detect the absence of self-molecules that are constitutively expressed on target cells. Specific receptors on the NK cells recognize MHC I antigens present on other body cells. The absence of these receptors is interpreted as “missing self.” This situation may occur with cells under stress; such cells are targeted for cytotoxicity by NK cells. In this way, NK cells show self-tolerance while being toxic to stressed cells. NK cells are found throughout the lymphoid and non-lymphoid tissues.

NK cells are of different types, based on whether they express CD56 and CD16. Both receptors are involved in immunity against viral infection. NK cells with strong CD56 expression but absence of CD16 receptors form only a small subset in healthy individuals; they have restricted cytotoxicity but high cytokine production. Most NK cells in circulation have low CD56 expression, proliferate slowly, have strong cytotoxic capability, and are able to acquire killer immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIRs) and other cell markers progressively as they differentiate. They also have a range of other receptors such as natural cytotoxicity receptors, signaling lymphocyte activation (SLAM) receptors, and C-type lectin receptors.

NK Cells and HIV

HIV-1 viruses need to escape immune surveillance at a long series of checkpoints to be able to replicate and survive within an immunocompetent host. For instance, HIV-1 is able to reduce cytotoxic activity of NK cells towards HIV-infected cells and decrease the priming effect of NK cells on other effector immune cells in the adaptive immune system. A third way that HIV-1 escapes elimination is by infecting a subpopulation of NK cells that is susceptible to the virus. These mechanisms mean that the body finds itself unable to fight the virus efficiently.

NK cells can suppress the replication of HIV viruses within CD4+ lymphocytes efficiently, primarily by the secretion of CC chemokine. This suppression is independent of interferon-gamma secretion and doesn’t require cytolytic activity. The greater the viremia, however, the lower the level of this NK cell-mediated suppression.

During the HIV treatment initiation with antiretroviral therapy, there is a marked increase in NK cells expressing CD56 and a decrease in NK cells expressing both CD16 and CD56. Other molecules that reflect alterations in immunity, such as galectin 9 and TIM-3, also change with ART initiation and are associated with increased NK cell activity. However, their interaction in the chronic phase of HIV may lead to dysfunction of NK cells. When TIM-3 is not properly expressed on NK cells, the CD4 cells fail to recover following ART treatment. Thus, NK cells appear to be essential to immune recovery in at least a subset of HIV-infected patients.

Chronic HIV infection also leads to increases in the number of CD56-CD16+ cells, which have low ADCC. A decrease in viral load is associated with restoration of normal ADCC activity. However, this effect is mediated by a reduction in NK cells’ antibody conferred activity by ART.

Conclusion

Knowing how NK cells will react to treatment is essential to planning effective therapy in a variety of patients. This requires the study of NK cell expression of receptors such as NKG2A receptors, which produce effects such as degranulation, interferon-gamma release, and CCL4 production at high levels when exposed to HIV-infected CD4+ cells. However, some HIV subtypes cause NK cell dysfunction.

Some work indicates that certain vaccines are capable of restoring NK-mediated interferon-gamma release to lyse infected CD4+ cells through NK activation and other pathways mediated by signals from recruited NK cells. Proper direction of the interaction between adaptive immune cells and NK cell responses can help make use of effective NK cell activation pathways. The restoration of this powerful immune response may help eradicate the virus and cure the infection using customized ART regimens in the future, especially when the immune system shows signs of dysfunction and anergy.

Further Reading

Last Updated: Nov 19, 2018