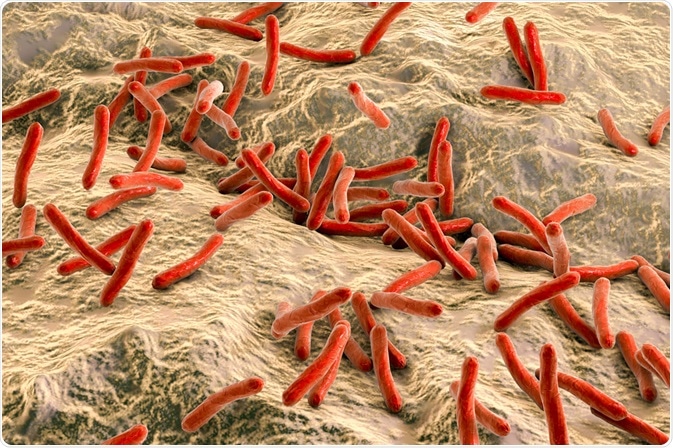

Leprosy is a slow but potentially devastating disease caused by the microbe Mycobacterium leprae (M. leprae).

Leprosy, which is otherwise referred to as Hansen's disease (HD), can be further classified as either paucibacillary (PB), multibacillary (MB) pure neuritic, or indeterminate leprosy. Although leprosy is not a life-threatening disease, it can have a significant impact on the physical, social, and psychological health of affected individuals.

Image Credit: Kateryna Kon | Shutterstock

Image Credit: Kateryna Kon | Shutterstock

Mycobacterium leprae: The causative organism

M. leprae is an acid-fast organism, which means that the cell wall of the bacterium contains large amounts of mycolic acid and waxes, as well as other complex lipids. This structural composition imparts a waxy consistency to the cell wall and enables M. leprae to resist decolorization following staining with carbol fuchsin, which is a dye that would otherwise give the cytoplasm a red color. This characteristic retention of carbol fuchsin is the reason M. leprae is known as acid-fast.

M. leprae is a fastidious organism, meaning that the in vitro culturing of this organism is very difficult. In fact, it was not until the late 1980’s that researchers were able to develop a suitable culture medium within which M. leprae would grow. A scarcity of available research tools, combined with the lengthy incubation period of M. leprae, resulted in considerable delays in determining the risk factors for leprosy.

While leprosy is a highly contagious disease, its clinical prevalence is relatively low in most populations. This immunity is attributed to the fact that approximately 90% of human beings infected with M. leprae are capable of generating a protective immune response to the bacillus.

Despite this figure, M. leprae is still being transmitted to human beings in at least 122 countries around the world. With more than 200,000 new leprosy cases emerging each year, 25,000 of which involve infections in children, there remains an urgent need for greater diagnostic and treatment efforts to be made in marginalized affected communities.

How is leprosy transmitted?

Current limitations in M. leprae research, combined with the long incubation period of the disease, have prevented researchers from fully understanding how the bacterium is transmitted.

Various transmission routes have been proposed, which include human-to-human transmission (e.g. skin to skin), the inhalation of contaminated aerosols in the form of Flugge droplets present in nasal secretions, as well as direct exposure to M. leprae through some type of trauma, or through exposure to contaminated water or soil sources. Carrier states are also thought to be involved in the transmission of leprosy.

A multitude of host factors is also thought to play a role in the spread of leprosy. For example, a genetic predisposition, immune function, and nutritional status appear to play a role in the progression of leprosy. In fact, variation in the manifestations of leprosy is believed to be a result of the differences in the genetic make-up of the susceptible host, the differential mechanisms of activating metabolic pathways by the microbe, as well as Schwann cell reprogramming.

Risk factors for leprosy

The limited information on the transmission of M. leprae makes it increasingly difficult to identify conclusions as to what risk factors are associated with this disease. While this may be true, research in this area has found correlations between the incidence of leprosy and the following factors:

- Close contact with infected individuals

- Genetic traits

- Age

Pathogenesis of the disease

M. leprae produces a chronic infection that primarily affects the peripheral nerves and skin; however, effects on the eyes, mucous membranes, bones, and testes may occur.

The leprosy infection manifests along a spectrum in which tuberculoid leprosy, which is characterized by a cell-mediated immune response that is capable of controlling the proliferation of M. leprae, is at the lower end and lepromatous leprosy, which involves the inability of a humoral response to combat M. leprae, is at the other end.

Leprosy and the nervous system

Within the nervous system, M. leprae is harbored within the myelinating Schwann cells that surround the axons of peripheral nerve cells. The attachment of M. leprae to the Schwann cells occurs through the interaction between specific adhesion molecules present in the basal lamina of the cell membrane, as well as ErbB2 or alpha-dystroglycan receptors present on the Schwann cell surface.

The bacillus enters the host cell and signals its dedifferentiation, thereby allowing it to take on characteristics of immature cells to ultimately promote bacillary proliferation.

The Schwann cell is not only dedifferentiated by M. leprae, but can also be transformed into an organism that closely resembles a stem cell. This stem cell-like organism can then become a mesenchymal cell that is capable of migrating to other parts of the body to facilitate further microbial infection. Additionally, M. leprae infection of Schwann cells can also produce an inflammatory response that results in granuloma formation to also promote further invasion of M. leprae to the rest of the body.

As the disease progresses, axonal conduction is eventually impaired and demyelination occurs, which ultimately leads to a loss of sensation in the affected limb(s). This results in deformity, repeated minor or major injuries, and, ultimately, permanent disability. In addition to steady nerve degeneration following M. leprae infection, another potent cause of sensory loss is attributed to periodic leprosy reactions, which can further increase inflammatory damage to peripheral nerves.

Leprosy and the skin

Within the skin, M. leprae migrates to keratinocytes, macrophages, and histiocytes.

Langerhans cells, which are epidermal dendritic cells that are in close contact with keratinocytes, normally function by capturing and transporting antigens to lymph nodes for presentation to immature T cells. Researchers have found that Langerhans cells play a role in the immune response against M. leprae.

Mast cells (MCs) in the skin, which play an important role in both innate and adaptive immune responses through their ability to recruit T cells, neutrophils, and eosinophils to the site of injury, have also been associated with the pathogenesis and innate protection of leprosy in the skin.

Image Credit: MR.PRAWET THADTHIAM | Shutterstock

Image Credit: MR.PRAWET THADTHIAM | Shutterstock

Leprosy reaction classifications

Leprosy reactions can be classified as type 1, which is otherwise referred to as reversal reactionsm or type 2 reactions, which are also known as erythema nodosum leprosum. Both of these reactions may precede, be concurrent with, or occur following treatment.

The effects of these reactions represent a drastic increase in immunologically-mediated inflammatory reactions that can occur around the peripheral nerves and ultimately lead to nerve compression and damage.

The prompt diagnosis and treatment of both leprosy reactions are therefore imperative for preventing the worsening of the sequelae. Common treatments for both reactions may include corticosteroids, thalidomide, TNF inhibitors, or T cell inhibitors, depending on the clinical signs and severity.

Alternative organisms

M. lepromatosis has been recently discovered in patients with diffuse leprosy of Lucio and Latapi, which refers to a widespread form of HD that is often associated with endothelial cell injury and necrotizing lesions.

References

- Sarkar, R., & Pradhan, S. (2016). Leprosy and Women. International Journal of Women’s Dermatology ; 117-121.

- Innovative tools and approaches to end the transmission of Mycobacterium leprae. Lancet Infectious Diseases 17; 298-305.

- Costa, M. B., Mimura, K. K. O., Freitas, A. A., Hungria, E. M., Sousa, A. L. O. M., et al. (2018). Mast cell heterogeneity and anti-inflammatory annexin A1 expression in leprosy skin lesions. Microbial Pathogenesis 118; 277-284.

Further Reading

Last Updated: Apr 26, 2021