Leukemia is the most common form of childhood cancers, with a prevalence rate of 10 – 45 per 100,0000 children in each year. Among various types of leukemia, acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) is the most common form, followed by acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML).

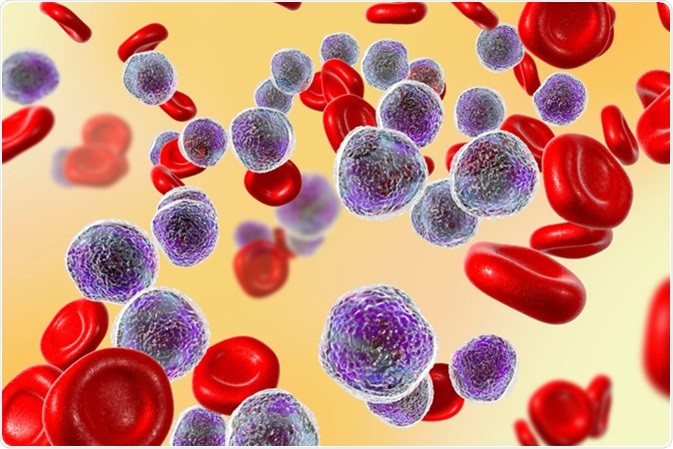

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia, bone marrow smear, 3D illustration - Image Credit: Kateryna Kon / Shutterstock

What are the symptoms of childhood leukemia?

Leukemia is a cancer of bone marrow, which is responsible for producing blood cells, including red blood cells (RBC), white blood cells (WBC), and platelets. Upon onset of leukemia, abnormal immature cells (myeloblasts) start growing very rapidly and competing with healthy cells for nutrition and space. This ultimately leads to abnormal bone marrow function.

Anemia is one of the common symptoms of leukemia, and develops due to inhibition of RBC production by bone marrow. The most common consequences of anemia in children are extreme tiredness, paleness, and rapid breathing rate.

Crowding of myeloblasts in bone marrow can significantly reduce the production of platelets, resulting in bleeding and bruise formation. A low platelet level causes formation of tiny red patches on the skin, which is known as petechiae.

Another important symptom is repetitive bacterial or viral infections, which are associated with recurrent fever, runny nose, and cough. Although WBC count is usually very high in children with leukemia, these cells are mostly immature and unable to destroy infectious agents.

Other symptoms of leukemia include bone and joint pain, abdominal pain, lymph node swelling, and dyspnea (breathing difficulty).

What is the connection between leukemia and childhood infection?

Genetic mutations and chromosomal abnormalities in bone marrow cells are believed to be responsible for leukemia development. These changes are mostly acquired and only around five per cent of leukemias are associated with inherited genetic syndromes.

One of the main risk factors that predisposes a person to leukemia is exposure to radiation. Cancer patients who undergo both radiation and chemotherapy are at higher risk for developing leukemia. In addition, certain chemotherapeutic drugs and chemicals like benzene are well-known risk factors for leukemia. Some genetic syndromes increase the risk of developing leukemia: Fanconi anemia and Down syndrome. Also, inherited genetic conditions that affect the immune system like ataxia telangiectasia, neurofibromatosis, and Li–Fraumeni syndrome may also increase a child’s risk of developing the disease.

Any impairment in the immune system can significantly increase the risk of developing leukemia. Children with immune disorders or taking immune-suppressing drug due to organ transplant are at higher risk. As a consequence of the impaired immune system, pathogen-induced infections are believed to play an important role in leukemia pathogenesis. In Japan and the Caribbean area, infections caused by human T-cell lymphoma/leukemia virus-1 (HTLV-1) are known to trigger the onset of a rare type of T cell ALL. Similarly, in Africa, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection is known to be a causative factor for Burkitt lymphoma and one type of ALL.

A growing body of evidence supports the hypothesis that exposure to infection triggers the development of childhood leukemia. There are two proposed mechanisms: delayed infection hypothesis and population mixing hypothesis.

According to the delayed infection hypothesis, onset of leukemia can be triggered by delayed exposure to common childhood infections, which is associated with an absence of immune modulation in the neonatal and infancy periods. Because of this reason, the immune system may function abnormally when exposed to such infections later in life (delayed). Subsequently, infection-induced abnormal immune signaling can induce a series of genetic events (two hit hypothesis), leading to the development of leukemia.

According to the population mixing hypothesis, a rare response to a common childhood infection of low pathogenicity can lead to development of leukemia. Population mixing can potentially increase the risk of cancer development because of interactions between infected and vulnerable populations.

Several animal experiments have been carried out to test the delayed infection hypothesis. For example, it has been found that genetically modified mice lacking a B-cell transcription factor PAX5 are susceptible to develop precursor B-cell ALL when exposed to common pathogens. Inactivation mutation of PAX5 results in secondary mutations of JAK3, which is responsible for the malignant transformation.

Another study in mice reveals that chronic infection and delayed exposure to robust inflammatory microenvironment can facilitate the acquisition of pre-B cells with pre-leukemic genetic lesions, such as ETV6-RUNX1 translocation, leading to development of childhood leukemia. Two classes of enzymes (RIG1/RIG2 and AID), which are responsible for somatic recombination and mutation of immunoglobulin (antibody) genes in B cells, function in synergy to destabilize genetic integrity and facilitate ALL pathogenesis by increasing the clonal selection of ETV6-RUNX1 translocation bearing pre-B cells.

Similar studies on humans have reported that children exposed to the influenza virus during 9 – 12 months of age are more likely to develop leukemia than those infected during the first three months of life. Similar results have been observed in case of respiratory syncytial virus.

Professor Sir Mel Greaves reveals likely cause of childhood leukaemia

Further Reading

Last Updated: Jul 30, 2019