Niacin is a water-soluble vitamin that participates in a variety of biochemical reactions in the human body. It is present in foods derived from plants and animals and is synthesized naturally from the amino acid tryptophan. Niacin deficiency disorders can arise as the result of an inadequate diet, excessive alcohol intake, and among people with certain types of cancer and kidney diseases.

Image Credit: Danijela Maksimovic / Shutterstock.com

People whose diet consists mainly of corn products are not acquiring adequate amounts of tryptophan; therefore, these individuals are unable to make the niacin they need to avoid developing pellagra. Pellagra is a deficiency state that affects the digestive system, skin, and nerves. In areas highly dependent on corn or maize, such as the United States and Europe in the early 20th century, pellagra was a common problem.

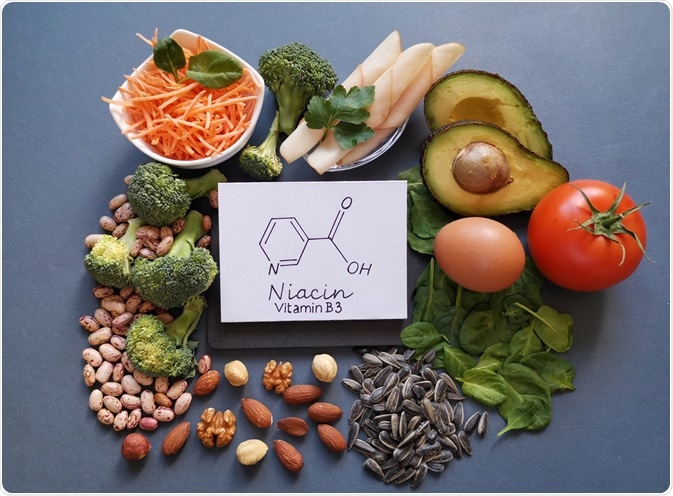

Distribution of niacin in foods

Animal protein represents the best source of niacin, including poultry, lean meat, fish, eggs, and dairy products. Cereals and breads that have been fortified with niacin and nuts are also providing a bountiful supply of this vitamin. Milk and eggs are rich in tryptophan, so they are also considered as good sources of this vitamin. Notably, human milk has a higher concentration of niacin than cows' milk.

In many cereals, especially in maize, niacin is present in a bound form known as niacytin. As digestive juices cannot break down niacytin, the niacin remains unavailable to the tissues of the body. Still, it can be liberated from niacytin when treated or digested with alkalis.

Niacin occurs as nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADP) in meats and thus it is much more fully absorbed. Niacin added for enrichment is also more available for absorption. Both nicotinic acid and nicotinamide are absorbed from the stomach and intestines. Subsequently, niacin is converted to NAD and NADP in practically any bodily tissue.

Niacin can be manufactured in the body from tryptophan, which is an essential amino acid. Nevertheless, the process is not quite effective, as the human body has many other uses for tryptophan. It takes approximately 60 milligrams of tryptophan to produce 1 mg of niacin.

The tryptophan content of breast milk is 210 mg/L; however, its conversion to niacin from milk is often overestimated due to the high protein turnover and net positive nitrogen retention in infancy. Also, diseases that prevent the tryptophan conversion are known, as well as medications that can interfere with the process.

Available nutrient and therapeutic preparations

As a dietary supplement, niacin is available in multivitamin formulations and in food fortification products. There are three main formulations for niacin, which include immediate-release (IR), sustained-release (SR), and a newer, extended-release (ER) niacin. Inositol hexanicotinate that contains both niacin and inositol is also available. All of these formulations differ in their pharmacokinetic, efficacy, and safety profiles.

Conventional niacin supplements have several limitations that include flushing, which is most often seen with IR formulations, as well as a toxic effect on the liver that is associated with SR formulations. These side effects are dependent on the absorption rate and metabolism of niacin as delivered from the different products.

Niacin extended-release (ER) has a unique delivery system that allows for the absorption of the drug over 8 to 12 hours. It was developed in order to achieve the lipid-lowering efficacy of niacin with a reduced incidence of flushing and hepatotoxicity. This formulation is approved for the treatment of dyslipidemia and available only by prescription.

References

Further Reading

Last Updated: Apr 7, 2021