Pelvic organ prolapse refers to a condition in women that occurs when the normal support of the vagina is lost, resulting in the descent of the bladder, urethra, cervix, and rectum from their normal anatomic positions. Based on pelvic examination, the prevalence of pelvic organ prolapse is somewhere between 30% and 50%.

Loss of pelvic support can occur when any part of the pelvic floor is injured during pregnancy, delivery, previous pelvic surgery, pelvic radiation or back fractures. Additional high-risk factors that can increase intra-abdominal pressure and lead to pelvic organ prolapse include constipation, obesity, chronic pulmonary disease, and heavy manual labor.

The pathophysiology of prolapse is multifactorial and a result of a “multiple-hit” process, in which genetically susceptible women are exposed to life events that eventually result in the development of clinically significant prolapse. The evaluation of women with prolapse necessitates a comprehensive approach based on detailed patient history, pelvic examination, and adequate testing.

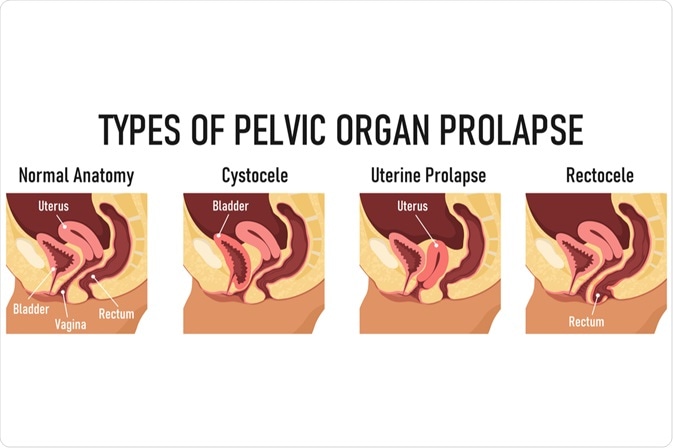

Types of pelvic organ prolapse

The type of pelvic organ prolapse in women is related to the location of the pelvis injury or muscular damage. It is not unusual to have several areas of injury, thereby resulting in several areas of prolapse. Patients generally present with several complaints including bladder, bowel, and pelvic symptoms; however, these symptoms are often not specific to prolapse, with the exception of vaginal bulging.

Image Credit: logika600 / Shutterstock.com

Anterior wall prolapse, which is often referred to as cystocele, is the most common type of pelvic organ prolapse. Cystocele occurs when the supportive tissue between the bladder and vaginal wall weakens and stretches. Consequently, the bladder drops and rotates into, and often out of, the vaginal opening. Some cystoceles can result in urine leakage, while large cystoceles can cause difficulty voiding.

Rectocele or posterior wall prolapse occurs when the posterior wall of the vagina loses its support. It represents a herniation of the front wall of the rectum into the back wall of the vagina. A typical rectocele symptom is straining to facilitate bowel movements, which is important to differentiate from simple constipation.

In uterine prolapse, the pelvic support is lost at the top of the vagina, which causes the uterus to drop down, often bringing the bladder or rectum with it. Mild cases of this condition may have no obvious symptoms; however, urinary retention or infections can be a consequence of a completely exteriorized uterus.

Up to 40% of women who have undergone a hysterectomy are at increased risk for developing relaxation of the top of the vagina, often referred to as vaginal vault. Sometimes the small intestines can slip into this prolapse of the vaginal apex, resulting in an enterocele.

What is Pelvic Organ Prolapse?

Prevention and management of the condition

Many women with pelvic organ prolapse are without any symptoms; hence, they do not need any specific treatment. When treatment is warranted, prolapse management choices fall into two broad categories of nonsurgical and surgical. Whereas a nonsurgical can include pelvic floor muscle training and pessary use, surgical treatment options for pelvic organ prolapse can be reconstructive or obliterative.

Behavioral modification and pelvic floor muscle exercises still represent the mainstay of conservative treatment, with a principal aim to reduce the symptoms, prevent the worsening of the condition, and avoid the need for surgery. The indications for pessary use are inoperable medical status due to certain comorbidities or refusal of surgery.

Surgery aims to restore physiologic anatomy, as well as preserve lower urinary tract, intestinal, and sexual functions. Some common types of surgical procedures that are used to treat pelvic organ prolapse include restorative surgery using the patient's supportive tissue, compensatory surgery using biological or synthetic materials, as well as obliterative surgery, which partially or completely closes the vagina.

References

Further Reading

Last Updated: Aug 17, 2023