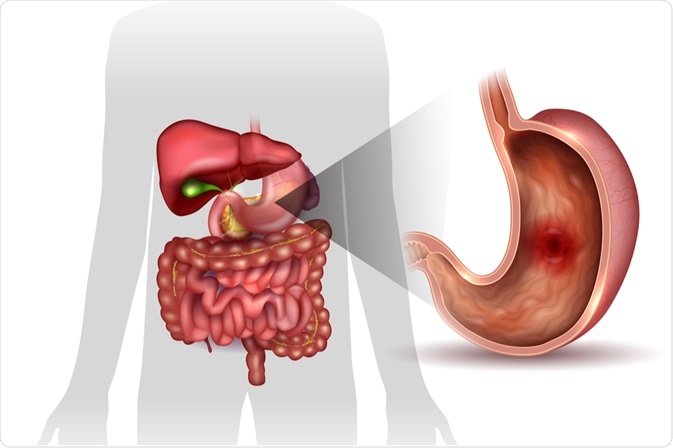

Peptic ulcers form in the inner lining of the esophagus, stomach, or duodenum of the small intestine. Peptic ulcers can occur when too much acid is produced in the stomach or if the protective gastric mucous layer is eroded due to irritation or inflammation.

Image Credit: Tefi / Shutterstock.com

Patients with peptic ulcers typically feel a burning pain in their abdomen or may experience nausea, vomiting, weight loss, or loss of appetite. It is important to properly diagnose and treat peptic ulcers, as untreated ulcers can result in complications such as internal bleeding. If left untreated, this internal bleeding can develop into anemia or severe loss of blood, scar tissues that can block the passage of food, as well as peritonitis, which is an infection of the abdominal cavity.

Helicobacter pylori tests

The number one cause of peptic ulcers is infection with the Helicobacter pylori bacteria. H. pylori is a spiral-shaped bacterium that embeds in the mucous layer of the stomach and small intestine, causing irritation and inflammation of the inner lining of gastric cells. A clinician who suspects a diagnosis of peptic ulcers after performing a medical exam may order an H. pylori test. This test measures the presence or absence of the H. pylori bacteria in a patient’s body and can be taken in a number of ways.

In the stool antigen test, the presence of H. pylori is determined by measuring the number of bacterial antigens, which are fragments of proteins, in a patient’s feces. Antibodies to H. pylori can also be measured in a patient’s blood. However, the presence of antibodies only detects exposure, which could indicate a current or previous bacterial infection.

The presence of H. pylori can also be detected by a breath test. To perform the breath test, a patient ingests a radioactive form of carbon. If the bacteria are present, the patient will exhale radiolabeled carbon dioxide. This conversion occurs because of the high levels of urea produced by the H. pylori bacteria.

H. pylori tests are quick and non-invasive, making them more common than other more invasive diagnostic tests. The presence of H. pylori, combined with corresponding patient symptoms, typically indicates the presence of a peptic ulcer. H. pylori infection can be treated with antibiotics.

Endoscopic tests

For some patients, such as those who are older or are experiencing severe pain or bleeding, a clinician may order an upper gastrointestinal endoscopic exam, called esophago-gastro-duodenoscopy (EGD). The endoscope is a thin, flexible tube with an attached lighted camera that is inserted in the mouth and passed down through the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum. An EGD allows the doctor to visualize these areas and look for ulcers.

Upper GI Endoscopy, EGD - PreOp Surgery Patient Education - Engagement

If an ulcerated region is detected, a small biopsy can be taken for further analysis. The biopsied tissue can be examined for the presence of H. pylori by examination under a microscope, conducting a chemical urease test, or through a polymerase chain reaction (PCR), which detects the bacteria’s genetic material.

Peptic ulcers can also be detected by a series of X-rays, called an upper gastrointestinal (GI) series. The patient ingests a white, chalky, barium-containing liquid to coat the stomach and duodenum, making ulcers more easily detectable in the x-ray. However, this method is less often used because of the improved visibility and potential to immediately biopsy suspected lesions during an EGD.

References

Further Reading

Last Updated: Sep 2, 2022