Consequences of bacteriuria

To treat or not to treat

Diagnosis

Treatment

References

Further reading

Pregnancy is a physiological state in which marked alterations occur in the structure and function of the urinary tract, encouraging pathogenic organisms to cause infection of the urinary system.

Pregnancy. Image Credit: Blue Planet Studio/Shutterstock.com

Pregnancy. Image Credit: Blue Planet Studio/Shutterstock.com

The urinary tract is dilated, and in 80% of pregnancies, this is accompanied by a small increase in the diameter of the renal pelvis, a condition called hydronephrosis.

This is attributed both to lower smooth muscle tone and reduced peristaltic frequency of the ureteral smooth muscle, along with the relaxation of the urethral sphincter, possibly due to the higher progesterone levels at this time.

In addition, the gravid uterus compresses the bladder and increases the pressure on the urine, causing it to reflux into the ureter as well as a predisposition to urinary retention after urination. During pregnancy, urinary excretion of sugars and amino acids is increased, providing food for uropathogenic bacteria and also ensuring an alkaline pH. These are factors that favor urinary tract infections (UTIs).

For this reason, a urine examination is routine for all pregnant women receiving antenatal care, to look for evidence of asymptomatic bacteriuria. Moreover, if found, this condition is treated because of the higher risk of pyelonephritis in this group.

Consequences of bacteriuria

Pregnant women have a small increase in bacteriuria compared to non-pregnant women since the female urinary system is exposed to the outside much more easily than in males.

Both asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB) and symptomatic UTIs are observed in pregnancy, with an estimated incidence of 2-13% and 1-4%, respectively. However, the consequences of UTI in pregnancy are far more severe than in any other group.

Many non-pregnant women already have ASB or UTI. This is associated with a doubling of the risk of bacteriuria in pregnancy. Interestingly, ASB itself has not been unambiguously shown to be a marker of increased risk of preterm delivery, though ASB progressing to UTI is.

GBS bacteriuria is also considered to be a marker for the presence of this organism in the reproductive tract, increasing the risk of preterm rupture of the membranes, preterm delivery and severe neonatal infection soon after birth.

Some of the adverse outcomes include pyelonephritis, which may occur in up to 40% of such cases; bacteremia in up to a fifth of pyelonephritis cases; a possibly increased risk of preterm labor and premature birth; pre-eclampsia; and low birth weight.

Very severe complications such as sepsis, hemolysis and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) may sometimes occur, especially if treatment is delayed.

For these reasons, UTIs in pregnancy are automatically classified as complicated infections. The adverse outcomes are thought to be the result of systemic inflammation and endothelial injury, with tissue damage caused by bacterial endotoxins.

Most infections during this time are caused by Enterobacteriaceae probably migrating from the gut, with up to 85% being accounted for by uropathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC). The rest are caused by bacteria including Klebsiella pneumoniae, Staphylococcus species, and group B streptococci (GBS).

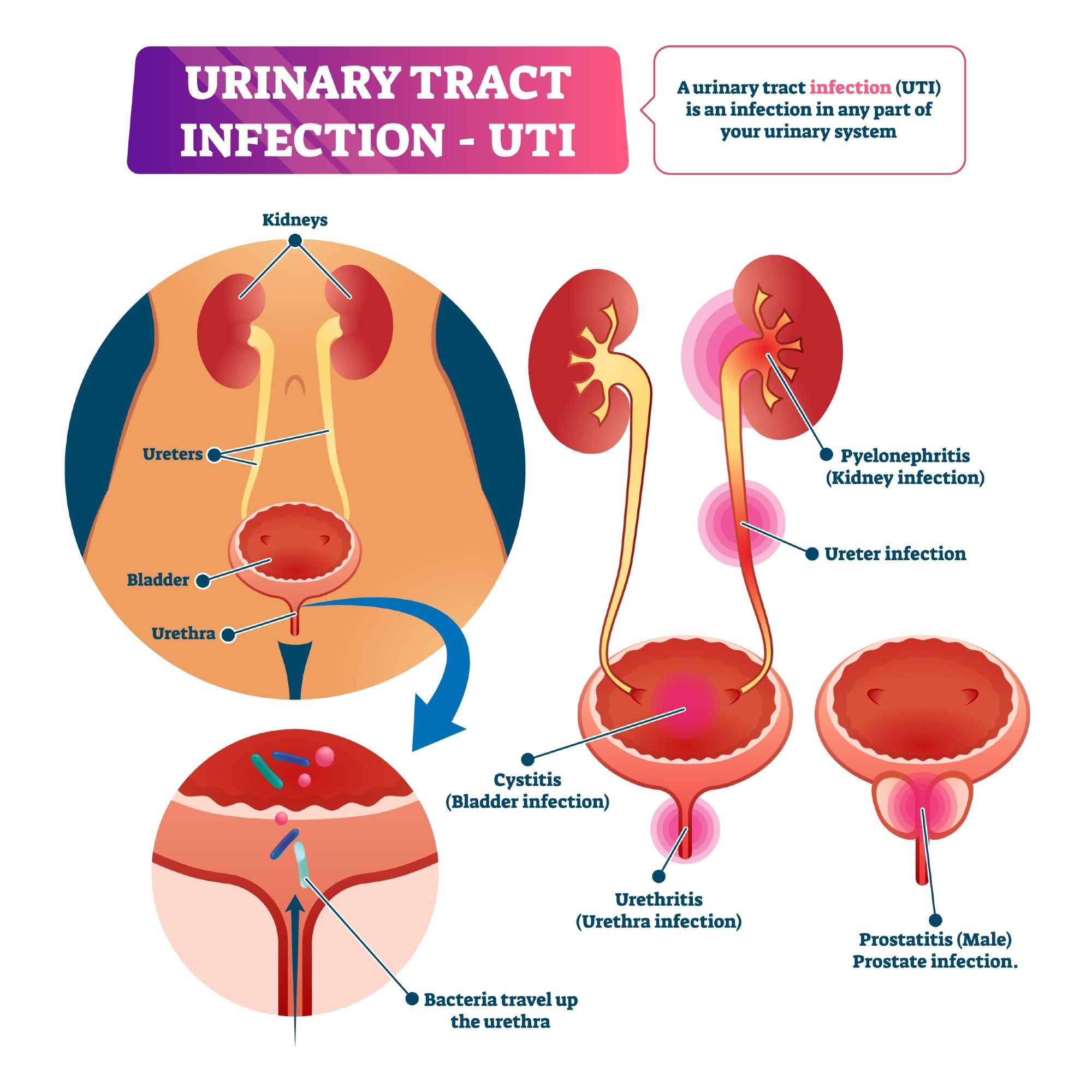

Urinary tract infection (UTI). Image Credit: VectorMine/Shutterstock.com

Urinary tract infection (UTI). Image Credit: VectorMine/Shutterstock.com

To treat or not to treat

While UTIs in pregnancy are sometimes problematic, their treatment with antimicrobials is also a challenge. Most of the antibiotics used in UTIs cross the placental, and some are teratogenic.

Penicillin and its derivatives, and the early cephalosporins, are commonly touted as safe in pregnancy but are of limited efficacy due to extensive drug resistance.

Antibiotics like cotrimoxazole and nitrofurantoin are usually avoided in the first three months, the period of organogenesis, but the potential of these drugs to cause fetal defects or harm is yet to be clearly demonstrated.

Both of these are considered safe thereafter and are often the first choice until the last prenatal week when they may trigger neonatal kernicterus. Cotrimoxazole also contains a folate antagonist, and folate supplementation is mandatory during its use.

Nitrofurantoin may cause hemolytic anemia in some women with glucose-6-phosphatase deficiency.

Fluoroquinolones are not recommended at any time, due to animal studies that demonstrated a higher incidence of cartilage defects. While more data is required to establish the safety of this group, many studies have not shown a higher risk of major malformations or preterm delivery.

Aminoglycosides may cause neurotoxicity and hearing loss. Tetracyclines can cause permanent discoloration of the teeth if given after the fifth month. Macrolides should not be given due to controversy over their teratogenicity, unless indicated for the treatment of life-threatening UTI with antibiotic resistance.

Amoxicillin-clavulanate was also associated with the same higher risk, especially when given with erythromycin.

Diagnosis

A single positive urine culture between the 12th and 16th week of pregnancy, or whenever the woman first presents for prenatal care, is suggestive of ASB, but with a 20% false-positive rate. In cases of doubt, a second test may be asked for within one week, to avoid unnecessary antibiotic prescriptions.

Repeated testing is recommended by some researchers, one in each trimester, to pick up more cases of ASB, but the relevance of this remains to be established.

Understanding Urinary Tract Infections

Treatment

Treatment should be prescribed for ASB and UTI, according to many scientists, as it could reduce the incidence of severe pyelonephritis.

Other experts demur the treatment of ASB, because of a lack of consistent association with preterm birth in the absence of symptomatic UTI, emerging risks of antibiotics to the fetus in the first trimester, and the rapid development of antibiotic resistance.

Pyelonephritis occurs in 2% of all pregnancies, which in itself is twice the incidence in the general population. Almost all cases of pyelonephritis occur in the second and third trimesters, and most follow symptomatic UTI, with a third being associated with a history of untreated ASB.

While one in five has septicemia at the time of diagnosis, preterm births were not increased, though transient renal dysfunction and lung complications occurred in these women.

Recurrent pyelonephritis is observed in less than a tenth of pregnant women, and repeated treatment with antibiotic prophylaxis is recommended for such cases. Such management is not evidence-based, however, and the standard of care produced comparable results in one study.

If treated, pregnant women with ASB are followed up with further urine screening once a month for the remainder of pregnancy. Some researchers recommend antibiotic prophylaxis, but hard evidence is lacking.

“The management guidelines were largely opinion-based. The development of new recommendations requires well-planned, extensive studies,” say the experts.

References

- Matuszkiewicz-Rowińska, J. et al. (2015). Urinary Tract Infections in Pregnancy: Old and New Unresolved Diagnostic and Therapeutic Problems. Archives of Medical Science. doi: 10.5114%2Faoms.2013.39202

- Smaill, F. Et Al. (2008). Asymptomatic Bacteriuria and Symptomatic Urinary Tract Infections In Pregnancy. European Journal of Clinical Investigation. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2008.02009.x

- Habak, P. J. et al. (2022). Urinary Tract Infection in Pregnancy. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537047/.

- Delzell, J. E. et al. (2000). Urinary Tract Infections During Pregnancy. American Family Physician. Available at: https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2000/0201/p713.html. Accessed on August 25, 2022.

- Kalinderi, K. et al (2018). Urinary Tract Infection During Pregnancy: Current Concepts on A Common Multifaceted Problem. Urinary Tract Infection During Pregnancy: Current Concepts on A Common Multifaceted Problem. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. doi: 10.1080/01443615.2017.1370579.

Further Reading

Last Updated: Jul 18, 2023