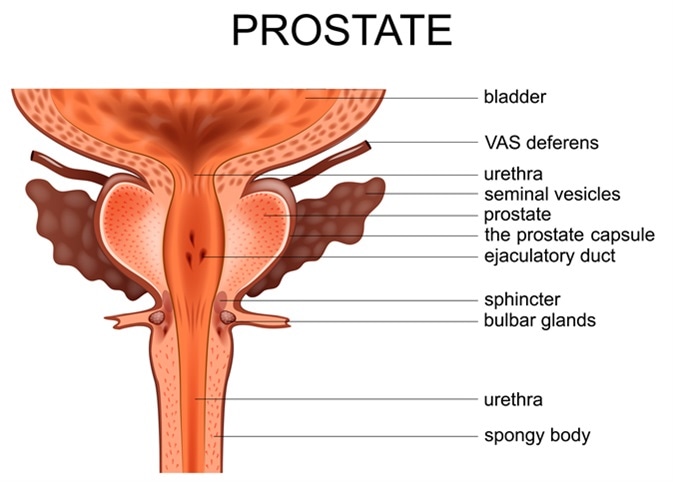

The prostate gland is a mass of tissue just below the urinary bladder in males, about the size of a walnut. It is situated in the region called the bladder base. It extends all around the urethra like a doughnut, surrounding the neck of the bladder.

Why is prostate anatomy important?

The prostate in humans is involved in three major disease conditions: benign prostatic hyperplasia, prostatic cancer, and prostatic inflammation.

The earliest descriptions of the anatomy of the prostate date back to the middle of the 1500s, to illustrations published by Andreas Vesalius.

Diagram of prostate from 1538 by Andreas Vesalius.

It has two main components: muscular and glandular, making it a compound gland. It has three lobes, one central and one on each side, the right and the left. It secretes fluids that drain through small tubes called ducts, into the enclosed part of the urethra lying within it.

Lobes of the prostate gland

The shape of the prostate allows it to be subdivided into a base and an apex, an anterior and posterior and two lateral surfaces. The base lies in close proximity to the lower surface of the urinary bladder and faces upwards. The apex points downwards and rests on the upper fascia of the urogenital diaphragm.

- The anterior lobe is solely fibromuscular, without glands.

- The median lobe is cone-shaped, lying between the urethra and the two lateral ejaculatory ducts.

- The lateral lobes are the bulk of the gland, and are separated by the prostatic part of the urethra, joining together behind it.

- The posterior lobe is the part that can be felt through the rectal wall on digital rectal examination.

There are a number of lymph nodes draining this region, such as the periprostatic, hypogastric and three groups of iliac nodes.

Illustration of prostate. Image Credit: Artemida-psy / Shutterstock

Zones of the prostate gland

The tissue of the prostate gland is also divided into three types of zones:

- The peripheral zone: this is the largest, and is located at the back of the prostate near the rectal wall. This is the area that a clinician can feel when performing a digital rectal exam. This is the area where 70% to 80% of all prostate cancers occur.

- The central zone: this is the region around the ejaculatory ducts and is the site least affected by cancer (less than 5%). However, these tumors are typically aggressive and invasive in behavior.

- The transition zone: this surrounds the urethra at the point of entry into the prostate gland. Initially small, it grows throughout life and its increasing size is responsible for the enlargement seen in benign prostatic hyperplasia. About 20% of prostate cancers arise here. Tumors in this region usually are associated with higher levels of PSA and are larger in size. However, they are slow to invade the seminal vesicles or the prostate capsule, and recurrence after treatment is unlikely.

What does the prostate do?

The prostate gland forms part of the male reproductive organs. It secretes a slightly alkaline fluid that is ejected into the urethra during intercourse, at male climax, forming part of the seminal fluid which carries sperm. The prostatic fluid is pushed into the urethra by the muscle in the walls of the prostatic glands. This fluid, in combination with sperm, forms semen, which is eventually ejected through the opening at the end of the penis during ejaculation.

Development of prostate gland

The early human embryo starts to develop prostatic buds from the epithelium covering an area called the urogenital sinus (UGS). These solid epithelial buds grow into the surrounding mesenchyme of the UGS to form cords of cells that eventually form a particular shape corresponding to the lobes of the prostate. The surrounding mesenchyme also forms fibroblasts between the muscle fascicles, and smooth muscle cells, even as the cords develop a lumen beginning from the urethral end. As androgen levels increase, the epithelial cells differentiate and produce more androgen receptors, to synthesize various specific substances.

After birth, the human prostate remains more or less static until puberty. At this point the sudden surge in androgen levels causes an increase in prostate size, which continues to grow slowly over several years. Once the prostate reaches adult size, it stops enlarging. Further size increase is not related to androgen excess, but to aging and a relative deficiency of androgen.

Further Reading

Last Updated: Mar 20, 2019