The retina is the light-sensitive layer inside the eye. It is made up of 5 or 10 layers, based on the anatomical classification. The innermost layer contains the rod and cone cells, which are rich in photosensitive pigments. These are called photoreceptors and are the actual organs of light reception.

The retina also contains several other types of nerve cells, notably the bipolar cells which receive light impulses from the photoreceptors. These are part of the next layer. The outermost layer contains the large ganglion cells whose axons finally transmit the impulses to the brain. These cell axons enter the retina at the back of the eye and lead back into the brain’s visual cortex. This spot is called the blind spot.

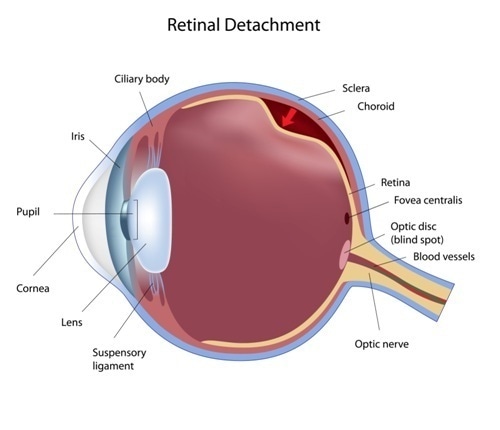

Eye condition: retinal detachment - Image Copyright: Alila Medical Media / Shutterstock

The retinal pigment epithelium

The retina rests on the choroid, from which it is separated by the retinal pigment epithelium layer. This layer is made up of melanin-rich cells. It nourishes the retinal cells and restores the visual pigments to activity after they are bleached by the action of light. It also removes the worn-out photoreceptor disks from the rods and cones, allowing for their proper turnover.

Vitreoretinal adhesion

The vitreous is a mass of jelly traversed by millions of collagen fibrils, which attach to the retina at certain spots. This is termed vitreoretinal adhesion. These spots include:

- The base of the vitreous where it is attached to the ora serrata of the retina

- The optic disk

- The macula, which is the central part of the retina where the cones are concentrated

- Along any areas of scarring

- Along the larger retinal blood vessels

- Along the edges of an area of lattice degeneration

- Vitreoretinal tufts

Posterior vitreous detachment

With advancing age, the vitreous loses its gel-like consistency. The fibrils become coarser, and liquefaction takes place. Finally the vitreous collapses on itself, leading to its pulling away from the retina, starting from the back of the eyeball. Finally, it peels off the macula and this leads to posterior vitreous detachment.

As the vitreous shrinks, the places where it is firmly attached undergo traction, and this may lead to retinal tears.

Retinal tears and retinal detachment

A retinal tear or break is any tear leading to a discontinuity in the full thickness of the retina. It allows fluid to seep underneath the sensory or photoreceptor layer of the retina, peeling it off from the retinal pigment epithelium underneath. This is called rhegmatogenous retinal detachment.

The most common cause of a retinal hole is posterior vitreous detachment.

Retinal holes may occur in lattice degeneration of the retina. This accounts for less than a third of rhegmatogenous retinal detachments. Only 2 in 100 atrophic holes, however, progress to retinal detachment.

Operculated tears are produced by traction and progress to retinal detachment in up to 20% of cases.

Flap tears that produce symptoms have up to 40% risk of producing retinal detachment, as opposed to 0-10% for those tears that are asymptomatic. The retinal break in such cases may be hard to find because it is covered by the flap. However, the same pull on the retina that produced the tear may also cause the retina to continue to detach. This may lead to clinical or subclinical retinal detachment. The presence of subretinal fluid is taken as a bad sign in such cases.

Overall, following an acute retinal tear, the risk of retinal detachment is about 52%, and this is the group that requires treatment.

References

Further Reading

Last Updated: Dec 30, 2022