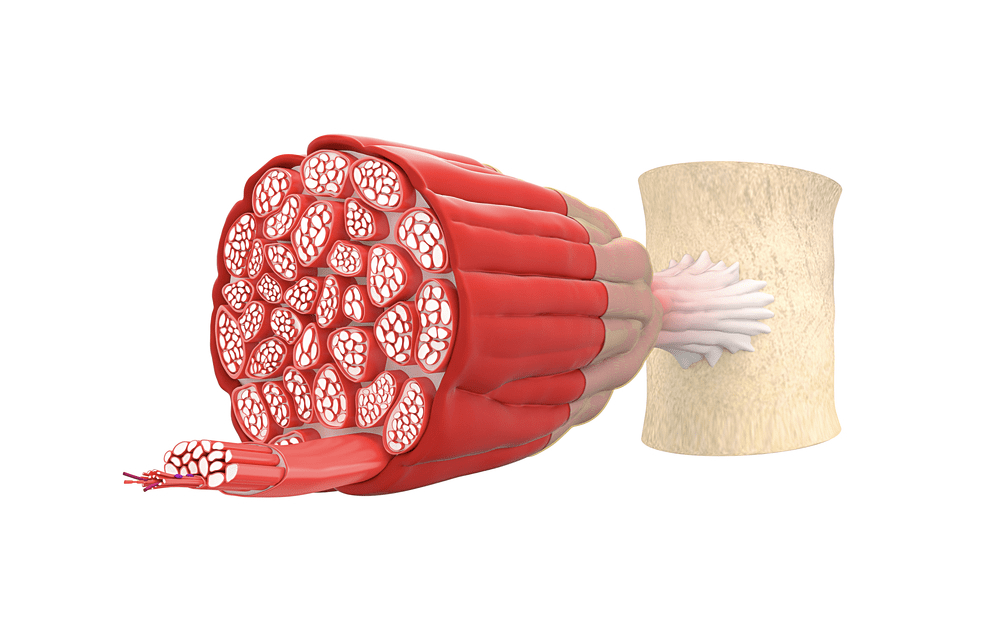

The term rhabdomyolysis is used to describe the breakdown or disintegration of striated muscle. Almost independent of the miscellaneous initial events, the pathogenesis follows a common final pathway with intracellular calcium accumulation and the depletion of adenosine triphosphate (ATP).

Many of the clinical features of rhabdomyolysis are nonspecific, and the course of the disease varies depending on the underlying condition. As some complications of rhabdomyolysis can be quite severe (such as hyperkalemia, cardiac arrest, and acute renal failure), early recognition and prompt management of this condition are pivotal for a successful outcome.

Image Credit: Anton Nalivayko / Shutterstock.com

Clinical presentation

Almost half of all patients with rhabdomyolysis present with the following triad of symptoms: myalgias, weakness, and brown-red colored urine due to the presence of myoglobin. A large number of patients presenting with calf pain or muscle swelling have their diagnosis confounded by other conditions, most notably of which include deep venous thrombosis (DVT).

Non-specific systemic symptoms, such as fever, abdominal pain, malaise, and nausea may also be observed. Proper assessment of symptoms can be hampered in patients with altered mental status, electrolyte imbalance, or uremic encephalopathy. The transaminases tend to be increased, which can lead to the condition being confused with acute liver injury.

Physical examination may reveal signs of dehydration, such as decreased skin turgor, delayed capillary refill, and dry mucous membranes. If trauma has occurred, the overlying skin is often bruised or discolored. With the development of compartment syndrome, the affected area is painful with specific sensory and motor deficits.

The most common complication of rhabdomyolysis is acute renal failure due to acute tubular necrosis as a result of mechanical obstruction by myoglobin. Acute renal failure is at a particular risk if serum creatine kinase levels are higher than 16.000 IU/l. The mortality rate of rhabdomyolysis is approximately 10%, with even higher rates reported in patients with acute renal failure.

Rhabdomyolysis - Mayo Clinic

Laboratory findings

The initial screening of rhabdomyolysis can be performed with a urine dipstick test. The orthotoluidine portion of the dipstick turns blue in the presence of hemoglobin or myoglobin; therefore, it can be used as a surrogate marker for indicating the presence of myoglobin if there are no red blood cells in the freshly spun sediment of urine.

The most sensitive laboratory test for detecting rhabdomyolysis is the detection of serum creatine kinase levels. As muscle cells disintegrate and release creatine kinase into plasma, the degree of its elevation shows a direct correlation with the degree of muscle necrosis.

Other muscle markers can also be used to support a rhabdomyolysis diagnosis. Aldolase, for example, is a glycolytic pathway enzyme that is found in a high concentration in skeletal muscle, as well as the liver and brain. Together with creatine kinase, an unusual level of aldolase in the blood is highly suggestive of muscle injury. An increase in the levels of carbonic anhydrase III is also specific for skeletal muscle injury, as it is not present in the myocardium.

Determining the levels of myoglobin, which is the skeletal muscle protein involved in oxidative metabolism, appears to be less sensitive for establishing the correct diagnosis in rhabdomyolysis cases. This is largely due to the fact that myoglobin is rapidly and unpredictably eliminated by hepatic metabolism.

In addition to these tests, directed laboratory testing aimed at uncovering the underlying cause of rhabdomyolysis is crucial. Such diagnostic evaluations may include toxicology testing, bacteriologic and viral tests, genetic analysis, muscle biopsy, and forearm ischemic tests.

References

Further Reading

Last Updated: Mar 17, 2021