Introduction

What is Sleep?

Sleep and the Circadian System

What Does Sleep Do?

Sleep and Cortisol

Sleep and GH

Melatonin

Sleep and Metabolic Hormones

Sleep and Sex Hormones

Sleep and TSH

Conclusion

References

Further Reading

Many people wonder how the lack of sleep affects their basic metabolism so profoundly. Sleep has been shown to interact with the endocrine system over a wide range of hormones, in both directions.

Sleep hormones. Image Credit: kanyanat wongsa/Shutterstock.com

What is sleep?

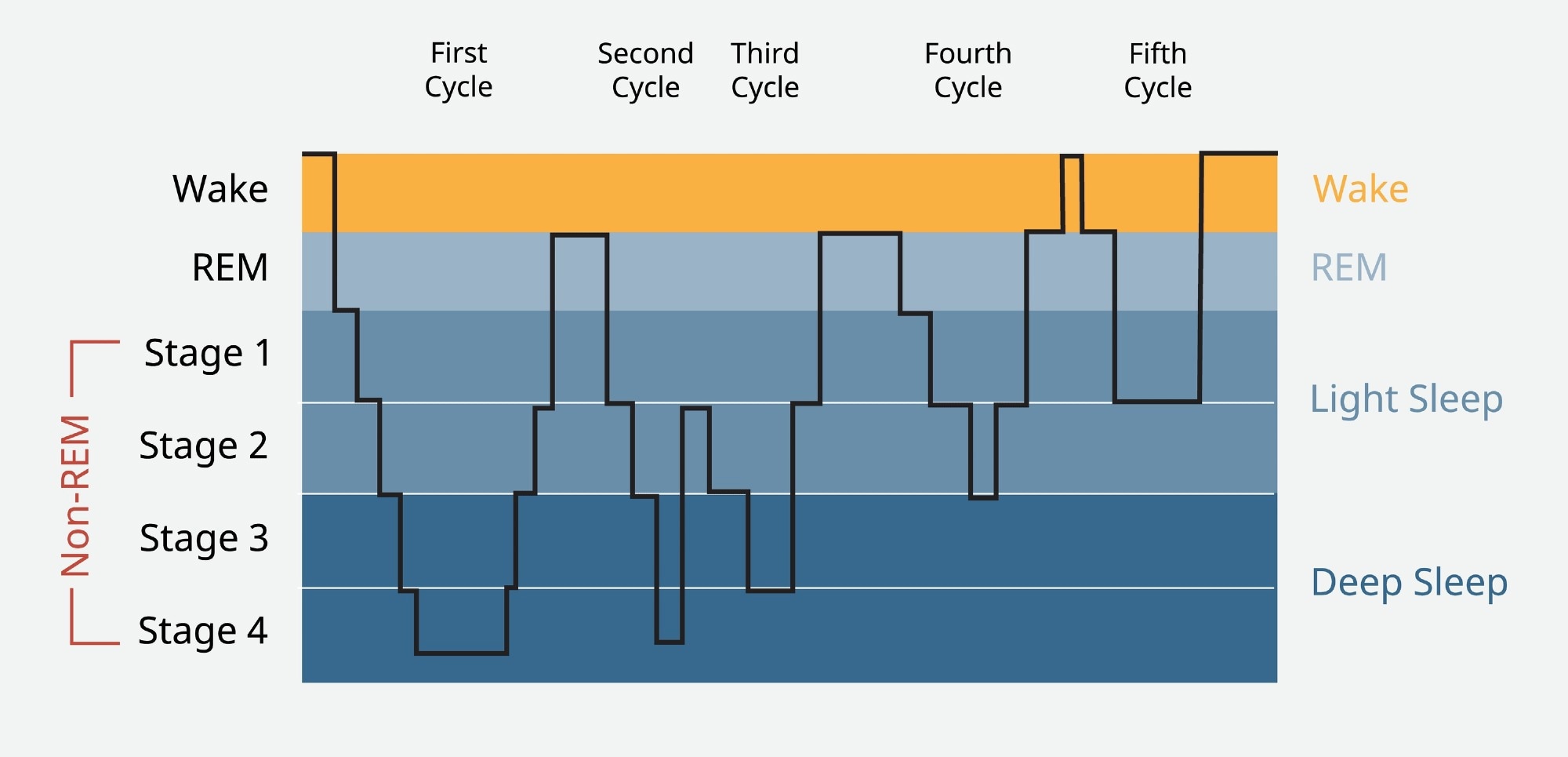

Sleep is a state in which consciousness is lost, and it becomes more difficult to rouse the sleeper by sensory stimulation, along with reduced motor function. However, it comprises several stages with varying patterns of brain waves, of which the most well-known are the Rapid Eye Movement (REM) and non-Rapid Eye Movement (NREM) sleep.

After beginning with NREM sleep from stages 1 to 3, characterized by orderly synchronized brain activity, the brain moves into a phase of deeper sleep with slower deeper delta waves, or slow waves. This is the phase of deepest sleep. While muscles are relaxed, they are not paralyzed.

REM sleep, or paradoxical sleep, occurs after slow-wave sleep (SWS, stage 3) is completed. The brain in the REM stage shows very disorderly brain waves, somewhat like that of the waking brain. Theta waves predominate, with a frequency of 4-8 Hz vs 0-4 Hz for delta waves. Skeletal muscles are paralyzed.

Sleep and the circadian system

Sleep is regulated by the circadian system and the sleep pressure system, the former working to wake the individual and the latter putting the individual to sleep. Sleep pressure is the need to sleep of any organism at a given moment. Both these systems work in parallel and are responsive to the external clock and the organism’s homeostatic processes.

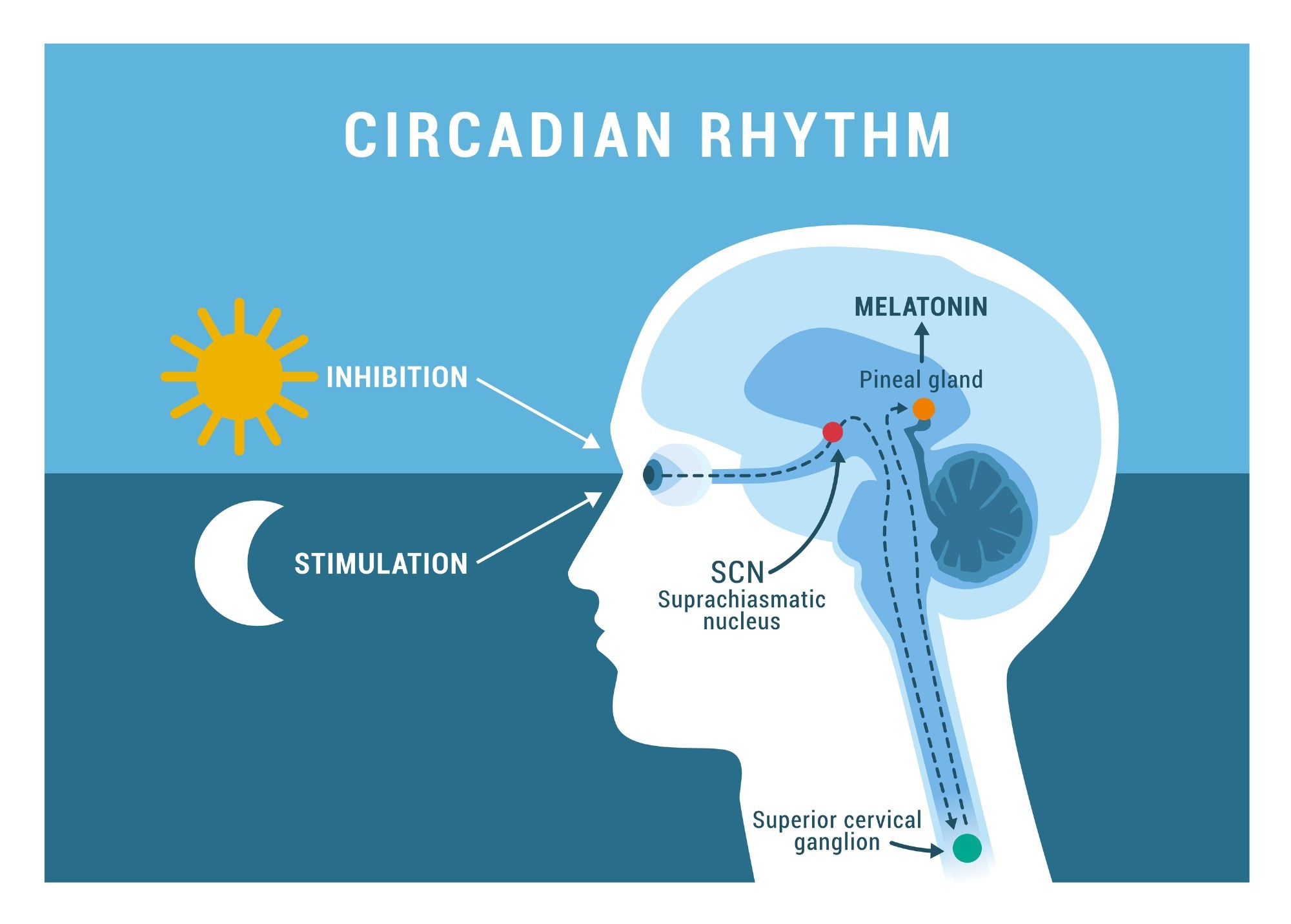

Circadian rhythms work on an endogenous beat, which is shifted by external cues including light and dark, exercise, food intake, temperature and some drugs and chemicals. The master circadian clock is the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the hypothalamus, the pacemaker which drives synchronized circadian rhythms in multiple peripheral organs.

With respect to sleep, the SCN enables the individual to sleep in long bouts related to external light and dark. Thus, external day and night are translated into biological day and night by the Circadian system, which also serves to regulate the daily rhythm of hormonal secretion and other biological processes.

The sleep pressure system determines how much sleep is required for the individual to return to the normal state, after any given period of waking. This tends to normalize the total amount of sleep required in a specified period, whether in tune with the Circadian rhythm or light-dark cues or not. It is considered to mediate the catch-up sleep that follows sleep deprivation.

What does sleep do?

Sleep has several physiological benefits, including:

- Glymphatic flow enhancement by a factor of 10

- Clearing metabolites and potentially toxic compounds that have built up in the brain over the awake state

- Consolidating memory

- Reducing synaptic strength uniformly which fosters the formation of long-term patterns of synaptic transmission. This is responsible for memory formation over the long term.

Moreover, sleep may be the key link between metabolic regulation and the endocrine system, reducing the onslaught of oxidative molecules on the brain.

Even more, sleep affects the levels of several hormones. Early studies have established a linkage between sleep and the secretion of key hormones like cortisol, luteinizing hormone (LH), leptin and growth hormone (GH).

Sleep and cortisol

The pituitary receives SCN projections in an oscillatory rhythm that keeps time with the day-night cycle, and also other SCN projections that result in the diurnal rhythm of cortisol secretion. This leads to a peak cortisol level early in the morning, immediately after waking, causing alertness in readiness for the activity of the wake cycle.

Researchers have found that sleeping at night, but not daytime sleep, suppresses the release of cortisol, the classic stress hormone. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis is thus affected by the sleep cycle. The light-entrained nature of cortisol secretion rhythms means that it is profoundly perturbed in night workers, or indeed whenever the Circadian rhythm is altered.

Both cortisol and the HPA axis regulate the stress response, which is inhibited by sleep. The administration of cortisol and other glucocorticoids induces SWS and blocks REM sleep, perhaps by inhibitory feedback on the corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH). Normally, CRH stimulates the HPA and enhances waking period duration.

Conversely, sleeplessness is linked to higher HPA activity throughout the day, with higher cortisol secretion over the latter part of the day, instead of its expected fall. This mimics aging, it is supposed, and leads to insulin resistance. Sleep also reduces the response of the adrenal gland to the action of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), again with the diurnal rhythm.

Sleep deprivation has also been shown to advance the nighttime rise in cortisol by one hour. Conversely, following the restoration of normal sleep, the rise occurred an hour later than at baseline.

Sleep and GH

GH levels surged during night-time sleep, with multiple increases approximately every two hours according to some scientists. GH is important for lipolysis and muscle growth and is related to sleep, rising during SWS and falling in late sleep.

However, during periods of sleep deprivation, GH levels failed to rise, rebounding following the restoration of sleep. During this period, a prolonged secretion in GH was noted, reaching a peak during slow-wave sleep (SWS). A second non-SWS peak was observed in restorative sleep after a period of sleeplessness.

This confirms that night-time sleep inhibits cortisol secretion at first, but is associated with a rise in GH levels – in fact, the nocturnal GH surge is largely during sleep. Sleep deprivation disrupts such associations, for GH at least, and changes the timing of the rise in cortisol.

Circadian rhythm. Image Credit: elenabsl/Shutterstock.com

Melatonin

Melatonin is the hormone best known to affect sleep, being low during the daytime but rising once darkness sets in, leading to sleep. Melatonin is secreted by the pineal gland, to which the SCN projects via multiple synapses to drive the Circadian rhythm of production of this hormone.

Melatonin pills have become popular as a sleep inducer, helping to synchronize light-dark cues with the Circadian rhythms. When melatonin is used outside its Circadian phase, it improves the total sleep period and helps to maintain sleep.

Interestingly, the beta-blocker atenolol increases total wake time, by suppressing melatonin secretion at night, but when melatonin is given at the same time, sleep returns to normal. In nocturnal rodents, however, peak melatonin levels accompany high activity levels, indicating a paradoxical melatonin effect on sleep physiology compared to humans.

Sleep and metabolic hormones

Early sleep causes an increase in ghrelin levels. Sleep disturbances also produce a rise in ghrelin and a fall in leptin levels, causing an increase in appetite and increased insulin resistance, probably because of disturbed GH levels. Conversely, ghrelin increases SWS and reduces REM sleep in males but not females at all ages.

Insulin levels also vary in rhythm with sleep, increasing during late sleep. This is probably linked to the SCN as well as to autonomous beta-cell self-regulation. Even minor sleep restrictions lead to alterations in insulin sensitivity, body weight and plasma leptin concentrations over a short period.

The insulin sensitivity in fatty tissue is much higher during the day than at night. As a result, disrupted sleep increases the risk of metabolic syndrome and its attendant conditions, such as obesity, when the effects on insulin, ghrelin and leptin are taken into consideration.

Sleep and sex hormones

Several lines of research suggest that there are sex differences in sleep quality, depending on the sex steroid levels. Ovarian hormones are closely associated with sleep patterns in female rodent studies, and estrogens seem to consolidate wake time but break up sleep in rats.

Interestingly, estradiol, the most potent estrogen, interacts with the circadian system in different ways depending on the time of day. It enhances sleep resumed after a period of deprivation during the normal sleep phase, but reduces sleep during the wake phase. Several neural circuits and nuclei that regulate sleep in rodents are being found to be linked to estradiol action via estradiol receptors.

Sleep has not been shown to affect female reproductive hormones, but testosterone levels peak towards the middle of the sleep cycle, around the time when REM sleep is about to begin. Too little sleep, or fragmented sleep, may arrest this rise, causing low testosterone levels. Testosterone may mediate the response of the SCN to light, enhancing its agreement with the Circadian rhythm.

Sleep cycle. Image Credit: Piscine26/Shutterstock.com

Sleep and TSH

The thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) also shows a suppressive effect of sleep, inhibiting its Circadian rhythm of secretion, and when sleep is resumed after a period of deprivation, the decrease in TSH levels is larger than with normal sleep.

Conclusion

Overall, “sleep and the endocrine system exhibit a bi-directional interaction, with sleep behavior having a strong influence on endocrine factors and endocrine factors reciprocally influencing sleep behavior.” Further research should uncover these links, especially with regard to sex hormones and biological sex.

Shift work and regular sleep deprivation enhance the risk of developing cardiovascular disease, obesity and issues with glucose metabolism by interfering with the Circadian rhythms of hormone secretion. It is worth pondering whether the modern desire for immediate access to almost all facilities is a goal to be pursued, or whether it would be healthier to go with the inbuilt need for sleep and restoration that resets the body’s metabolism to face and cope with each new day.

References

- Davidson, J. R. et al. (1991). Growth Hormone and Cortisol Secretion in Relation to Sleep and Wakefulness. Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1188300/

- Smith, P. C. et al. (2019). Neuroendocrine Control of Sleep. Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences. https://doi.org/10.1007/7854_2019_107. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6986346/

- Morris, C. J. et al. (2013). Circadian System, Sleep and Endocrinology. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. https://doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.mce.2011.09.003. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3242827/

- Kim, T. W. et al. (2015). The Impact of Sleep and Circadian Disturbance on Hormones and Metabolism. International Journal of Endocrinology. https://doi.org/10.1155%2F2015%2F591729. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4377487/

- Robertson, M. D. et al. (2013). Effects of Three Weeks of Mild Sleep Restriction Implemented in The Home Environment on Multiple Metabolic and Endocrine Markers in Healthy Young Men. Metabolism. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.metabol.2012.07.016. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22985906/

- Reynolds, A. C. et al. (2012). Impact of Five Nights of Sleep Restriction on Glucose Metabolism, Leptin and Testosterone in Young Adult Men. PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0041218. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3402517/

- Kluge, M. et al. (2010). Ghrelin increases slow wave sleep and stage 2 sleep and decreases stage 1 sleep and REM sleep in elderly men but does not affect sleep in elderly women. Psychoneuroendocrinology. DOI: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.07.007. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19647945/

- Weikel, J. C. et al. Ghrelin Promotes Slow-Wave Sleep in Humans. American Journal of Physiology, Endocrinology and Metabolism. DOI: 10.1152/ajpendo.00184.2002. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12388174/

Further Reading

Last Updated: Jul 7, 2022