Combined oral contraceptive pills (OCP) act by inhibiting ovulation at the level of the pituitary and hypothalamus, via suppression of gonadotropin secretion.

Contraceptive pill. Image Credit: WindNight/Shutterstock.com

The estrogen component prevents the increase in follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), thus inhibiting the formation of a dominant follicle. The progestin molecule inhibits luteinizing hormone (LH) secretion and thus keeps the LH surge from occurring. Both together prevent the occurrence of ovulation.

Progesterone is not normally present at significant levels in the non-luteal phase of the normal menstrual cycle. During the luteal phase, the endometrium has already become thickened and it is now decidualized by the action of progesterone. With a combined OCP, the progesterone shows stronger activity than the estrogen, causing the endometrium to become thin but decidualized.

The endometrial glands show atrophy, and the uterus is not receptive to implantation if fertilization occurs. Additional contraceptive effects are caused by the change in cervical mucus characteristics to become thick and impermeable. This keeps sperm from swimming up to reach the uterine cavity and then the fallopian tubes, where fertilization occurs.

Moreover, the tubal motility decreases, hindering sperm and ovum movement through the fallopian tube and thus preventing efficient fertilization.

With progestin-only pills, effective contraception is possible, but the addition of estrogen adds to its efficacy by preventing follicular development, stabilizing the endometrium and perhaps preventing breakthrough bleeding, which is more common with the former. Estrogen also upregulates estrogen receptors within the cells, allowing for the dose of progesterone to be reduced.

Extended and continuous-use pills

Traditional oral contraceptive pills are designed to deliver a low dose of female sex hormones, either estrogen and progesterone in combination, or progesterone alone, for 21 days, with a fourth week without any hormones. This leaves time for endometrial shedding, called withdrawal bleeding.

However, this phenomenon is quite different from menstrual bleeding and is not really essential for a woman’s health. For this reason, many scientists in the field of reproductive health have been examining the feasibility and safety of using birth control pills continuously, without monthly withdrawal bleeds.

There are two ways in which this can be done. One is called continuous-use birth control and the other is extended-use birth control. In the first type, the hormone pills are taken without a break for a year or more, which means there are no withdrawal bleeds. In the second case, the active pills are taken for more than 21 days, thus reducing the number of withdrawal bleeds experienced over a year, but not stopping them altogether.

Almost any combined estrogen-progestin oral contraceptive can be used in either of these ways. However, some formulations are available that are specifically designed to provide a longer gap between periods, with active pills being taken for 84 days (12 weeks) or one year, respectively.

Mechanisms of action of extended- or continuous-use pills

With the typical 28-day pill cycle, active hormones are taken for 21 days, during which time progesterone action is observed on the endometrium. During the next 7 days, the placebo allows unopposed estrogen action. Since there is no FSH inhibition, estradiol is produced by the ovaries.

This leads to endometrial growth which is promptly suppressed by the active pills. The aim of continuous- or extended-use is thus to eliminate the growth of the endometrium, thus preventing withdrawal bleeding. Breakthrough bleeding occurs due to endometrial atrophy and not endometrial shedding, as there is no thickened decidualized endometrium to shed.

What are the benefits?

Continuous- or extended-use OCPs are highly effective in preventing pregnancy.

For cyclic OCPs, with typical use, as contrasted to perfect use, the pregnancy rate is 8% vs 0.3% per year, respectively, showing that missed pills or other reasons for imperfect use cause unplanned pregnancies to occur at a higher rate.

The seven-day pill-free period with conventional cycles reduces the inhibitory effect of the pills on ovulation, increasing the risk that it will occur with one or more missed pills. The highest risk may be with pills missed early in the cycle or when the number of days in the break is increased.

This risk is reduced since there is no break in active pill use, and hence a lower chance of missing the start date for active pills. No significant difference is seen with contraceptive efficacy in cyclic vs extended- or continuous-use OCP.

The breakthrough bleeding is associated with a shift from mostly proliferative endometrium to inactive or benign endometrium, with no evidence of malignant change. Periods resume within 60 days of stopping continuous OCP use in the vast majority (95%) of women, and a high percentage – over 80% – became pregnant within a year of stopping this use pattern.

Delayed periods are beneficial for women who suffer from various menstrual-related symptoms, such as heavy, prolonged, painful or frequent periods. This option is also worthwhile for those who may find it difficult to keep themselves clean and change tampons and pads, due to mental or physical disability.

Conditions that are aggravated by menstruation such as endometriosis or anemia may also be benefited from this treatment, as also premenstrual bloating, mood swings, premenstrual tension, headaches, or breast tenderness. Some women develop migraine and other headaches in the week off active pills, which can be avoided by continuing them without a break.

Sometimes continuous pill taking is resorted to for the sake of convenience, as when a special event or vacation is planned and the woman does not want to have to deal with bleeding at that time.

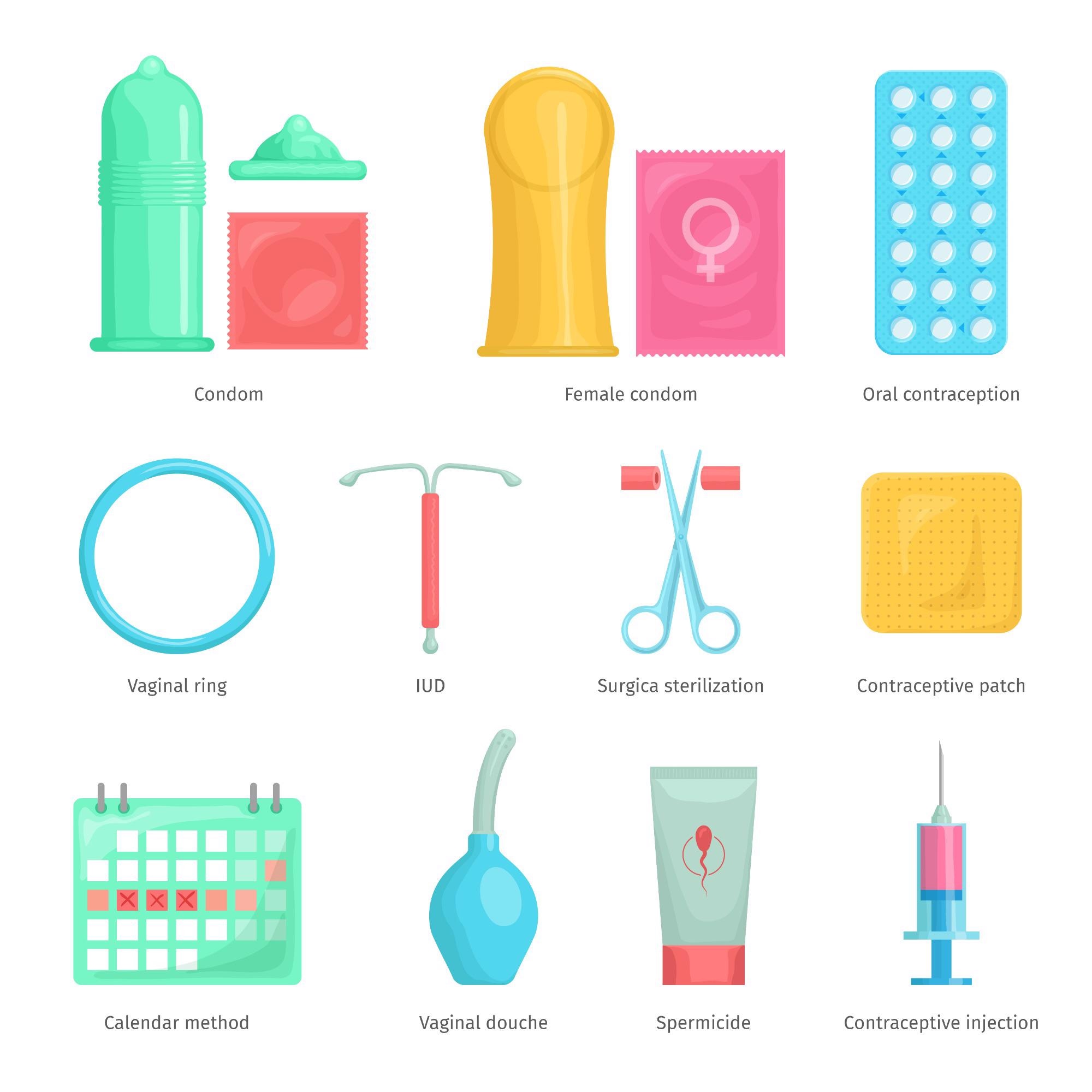

Contraception. Image Credit: Sunflowerr/Shutterstock.com

What are the risks?

Delaying periods for a long time can cause a higher rate of breakthrough bleeding or spotting – bleeding between periods – that can be inconvenient or embarrassing. This is more often experienced in the first few months of continuous use. As the physiology adapts to the low-dose continuous regimen, such phenomena typically decrease over time.

Breakthrough bleeding is more likely if the woman fails to take a pill on time, or also uses drugs that speed up the metabolism of the hormones in the contraceptive pill. The herbal supplement St. John’s wort also has the same effect. With vomiting or diarrhea, the pill is absorbed less efficiently, which can cause breakthrough bleeding due to lower hormonal effects on the endometrium.

Breakthrough bleeding can usually be prevented by carefully taking the pills on schedule. A missed pill makes it more likely that spotting will occur at some point. Tracking breakthrough bleeding carefully will also show if, as expected, it is reducing over time.

In case of uncontrollable breakthrough bleeding, it may be better to go back to the typical 21-day cycle with one week of inactive pills before the next active hormone pill course. Sometimes, it may be feasible to stop for three days after at least 21 consecutive days of the active pills, to allow bleeding to occur. This should be followed by the active pill for 21 or more days, counting from the fourth day after stopping.

Quitting smoking is also helpful for some women.

Cautions

It is important not to stop taking the pill because of troublesome breakthrough bleeding, as this may cause unplanned pregnancy to result.

Continuous use of contraceptive pills may also hide the rare case when pregnancy results due to contraceptive failure. This is because the universal sign of pregnancy – delayed periods – is now the norm. For this reason, women on continuous-use contraceptives should get a pregnancy test if they develop nausea and vomiting without an obvious cause, new breast tenderness, or unusual tiredness.

Heavy breakthrough bleeding should prompt a visit to the doctor, as should breakthrough bleeding that lasts for more than 7 successive days.

Certain conditions increase the risk of oral contraceptive pills. Women who smoke and are older than 35 years may find another option to be more suitable. Women who have just delivered a baby, and those with certain health issues related to the cardiovascular system, such as high blood pressure, ischemic heart disease, breast cancer, gallbladder disease, migraines with aura, long-term diabetes or diabetic complications, and systemic lupus erythematosus, as well as some liver conditions, are not recommended to use oral contraceptives.

Conversely, such women are often able to use progestin-only pills, with the exception of breast cancer and liver disease. The use of oral contraceptives containing estrogen seems to be associated with an increased risk of cervical cancer, directly proportional to the duration of use in total. This risk begins to decrease when the pills are stopped, returning to baseline at about a decade after stopping pills.

There was a small difference in venous thromboembolism (VTE) risk between continuous- or extended-use and cyclic use, which was real but so small that it may not make an actual clinical difference.

Certain studies, but not all, also suggest a small increase in the risk of breast cancer in women who have ever taken oral contraceptives containing estrogen. Progestin-only pills are not linked to either type of cancer at increased rates.

Conclusions

Continuous use of OCPs is both safe and reliable as a method of contraception, with the hormonal and metabolic effects being similar to cyclic use. Reduced period frequency is desirable for women with dysmenorrhea and menstruation-related symptoms, with good patient satisfaction.

There are no additional contraindications to the use of continuous OCPs than those in force for cyclic OCP use, and endometrial changes are beneficial with the former compared to the latter.

References

Further Reading

Last Updated: Feb 21, 2022