The urinary microbiome

Origin

Urobiome in UTIs

The urobiome in the sexes

The urobiome with age

Renal disease and the urobiome

The urobiome and cancer

The urobiome and incontinence

Other urological syndromes

What are the conclusions?

References

Further reading

The human host harbors an incredibly large number of microbes on the skin and the mucosa of the various tracts communicate with the exterior. They are grouped into several groups of microbiota depending on the ecological niche they occupy. Altogether, there are up to a thousand bacterial species in the human microbial community.

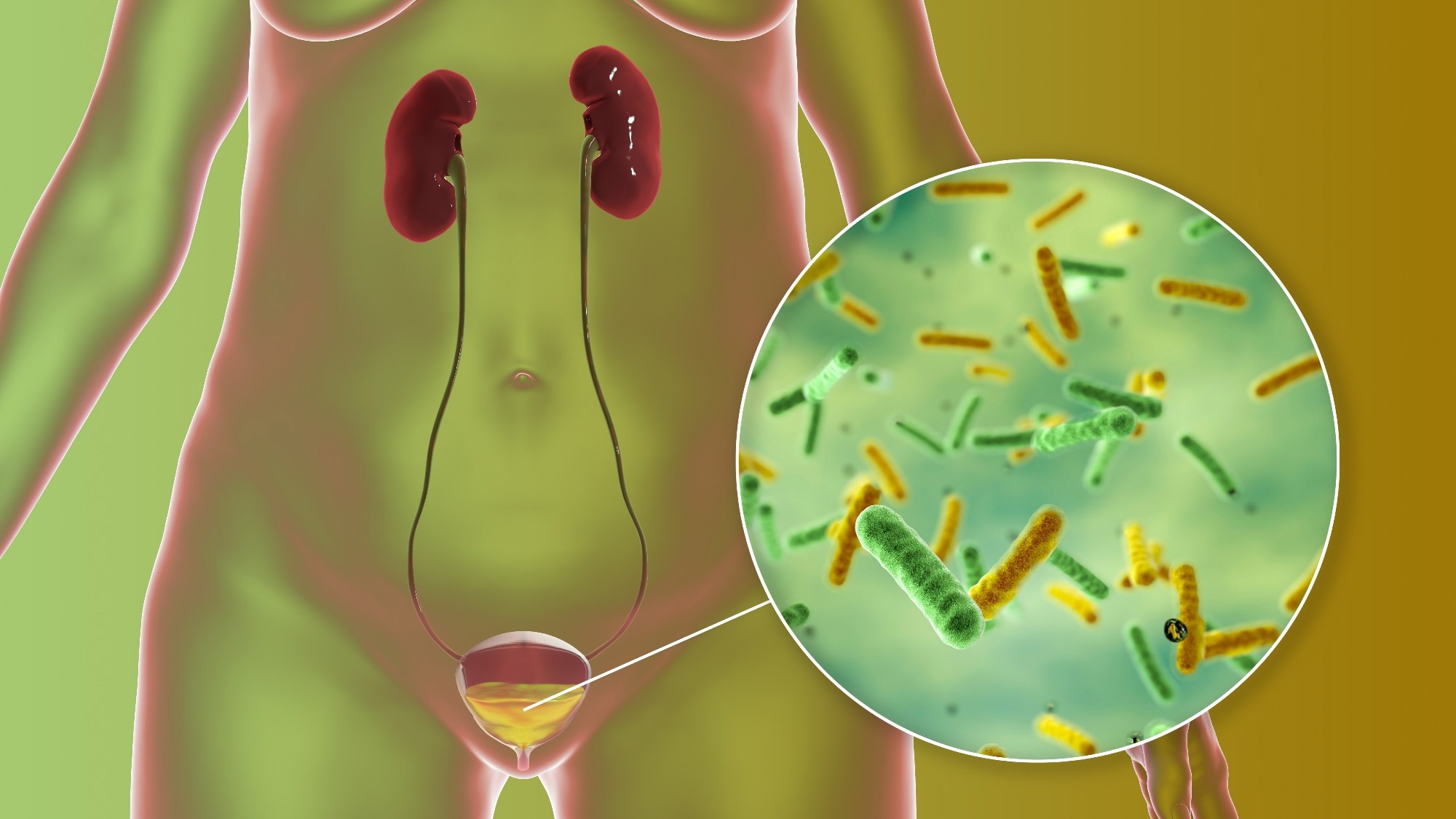

Urinary tract infection. Image Credit: Kateryna Kon/Shutterstock.com

Urinary tract infection. Image Credit: Kateryna Kon/Shutterstock.com

The microbiome represents the entire set of microbial DNA within the specified niche. This includes the human microbiome, the skin microbiome, the gut microbiome, the vaginal microbiome, and most recently, the urinary microbiome or urobiome. Apart from bacteria, there are viruses, fungi and protozoa in and on the human body.

The microbiome has been demonstrated to be key to the proper evolution of a healthy immune system and other physiological functions, including the production of multiple vitamins and neuroprotective compounds. Moreover, it also prevents the colonization and/or overgrowth of pathogens.

The normal gut flora can be wiped out or severely reduced in number by broad-spectrum antibiotic use, which can have many negative consequences. For instance, colitis commonly occurs as a result of the overgrowth of Clostridium difficile. This is an example of the importance of reasonable antibiotic use.

The urinary microbiome

Not many years ago, most scientists perceived the urinary tract as being sterile in normal conditions. However, metagenomics studies, as made feasible with the use of high-throughput next-generation sequencing (NGS) methods, have shown this to be a false dogma, with the urobiome being an integral part of the human microbiome.

The full characterization of the urinary microbiota is still a work in progress. Both bacteria and viruses are present in the urobiome, as well as bacteriophages. However, the microbial load is low compared to other microbial communities in the human body, and the presence of other niches nearby with large numbers of microbes makes contamination a very real possibility.

Origin

The urinary microbial community may have arisen in females from the vagina, with both vaginal and bladder flora showing close similarities between both commensals and potential pathogens. This has led at least some researchers to postulate the existence of only one community, the urogenital microbiota.

Others disagree, considering the gut to be the putative origin of the urobiome. Whatever its origin, the urinary microbiome shows changes in composition that are linked to different disease states, including urinary tract infections (UTIs), transitional cell carcinomas (TCCs) of the urinary tract, urgency incontinence, and overactive bladder. The urobiome may promote immunomodulation of the human host, especially during disease states of the urinary tract.

Urobiome in UTIs

UTIs are the most commonly found hospital-acquired infection of clinical significance and are potentially serious. Escherichia coli is found in both healthy and asymptomatic individuals, and other factors may be involved in its pathogenicity such as the presence of other infectious agents, especially Enterococcus fecalis.

In fact, E. fecalis can send out signals that trigger environmental changes, preparing the way for other coinfections. For instance, it can secrete the amino acid L-ornithine, which is essential for E. coli to produce enterobacterium siderophore under conditions of restricted iron availability. This helps E. coli to survive and grow in this situation, by creating its own biofilm.

Short-term exposure of the urinary tract to some strains of Gardnerella vaginalis can also cause dormant bladder strains of E. coli to become active, triggering UTIs. Women with bacterial vaginosis are also more prone to recurrent UTIs compared to those with Lactobacillus-dominant vaginal microbiota. This could indicate the risk of UTI following brief exposures of the urinary tract to vaginal or gut microbes that are not usually considered uropathogens.

Such conclusions are also supported by recent NGS findings, where disruption of the urobiome rather than exogenous invasion is considered responsible for urosepsis. Certain archaea have been reported in the urobiome as well, and some of them may also cause urinary dysbiosis promoting the growth of uropathogens and triggering UTIs.

The urobiome in the sexes

The urobiome in women has been found to be dominated by Lactobacillus, while that in men shows predominantly the presence of Gram-positive bacteria such as Corynebacterium and Streptococcus, both of which may act as opportunistic pathogens.

Gardnerella and Prevotella are also dominant in women, and some researchers report eight or more urotypes associated either with health or certain disease conditions.

The urobiome with age

With age, the relative abundance of species such as Lactobacillus, Bifidobacteria, or Bacillus is observed to decrease in females, with an increase in others like Mobiluncus and Oligella. Four genera, namely Jonquetella, Parvimonas, Proteiniphilum and Saccharofermentans, are thought to be found only in people over 70 years.

Renal disease and the urobiome

The urobiome may also be important in the etiology of chronic kidney disease (CKD) and kidney transplantation.

In CKD, the urobiome diversity is decreased in end-stage renal disease, and in kidney recipients. In the latter, the urobiome is dominated by potential pathogens such as Escherichia coli or Enterobacter, irrespective of the condition underlying the need for kidney transplant.

Interestingly, all recipients had highly similar urobiomes beginning one month after transplant, and persisting six months later.

The urinary virome is also deeply implicated in graft loss in kidney transplant patients, for example following BK polyomavirus nephropathy (BKVN). Bacteriophages are also abundant and may be more abundant than lytic viruses.

The urobiome and cancer

TCCs or urothelial cancers form the bulk of bladder cancers, with chronic UTI being a common risk factor. This obviously indicates a potentially significant role for the urobiome, given that bladder cancer is the tenth most common type of cancer globally.

Research suggests an increase in certain pathogenic bacteria in TCC and prostate cancer patients, as well as commensals. Such dysbiosis may modify the extracellular matrix, promoting chronic inflammation and a higher risk of carcinogenesis.

Understanding Urinary Tract Infections

The urobiome and incontinence

Urinary incontinence (UI) is more common in women, especially following childbirth, and may be classified as stress UI (SUI), urgency UI (UUI), and mixed UI (MUI).

Studies based on bacterial sequencing have suggested that urinary dysbiosis is associated with a higher risk of UUI, perhaps via the increased or decreased release of ions favoring or inhibiting muscular contractions that regulate the release of urine from the bladder.

Conversely, no hallmark associations have been found for SUI so far. With MUI, changes in the composition of the urobiome have been found, probably due to the UUI component.

Other urological syndromes

Other bladder syndromes possibly related to urinary dysbiosis include overactive bladder, neuropathic bladder, and interstitial cystitis, as well as chronic pelvic syndrome.

In nephrolithiasis, a reduction in diversity with a change in the overall composition of the urobiome has been described, with altered levels of metabolites of nucleotides and increased microbial nitrogen production. Hypertension in nephrolithiasis patients has also been described in association with dysbiosis of the urobiome.

What are the conclusions?

The treatment of urinary tract disorders could be effectively modified by using the results of urobiome characterization studies.

Targeted antibiotics are necessary to prevent the proliferation of pathogens in the gut microbiota resulting from the kill-off of commensals, which in turn promotes UTIs. Again, intracellular bacteria are sometimes triggered by low concentrations of certain antibiotics to release muscle contraction-stimulating ions like calcium, which could eventually lead to conditions like UUI.

Urinary dysbiosis due to antibiotic therapy is another possible complication, while the response to treatment is also modulated by urobiome diversity. Probiotics and prebiotics may encourage commensals to colonize the urinary tract, reducing the incidence of UTIs. Conversely, cranberry juice might reduce E. coli adhesion and colonization.

Lysogenic bacteriophages are another tool that could help treat UTIs, including those with multidrug resistance. Further research is essential to explore their potential role.

References

Further Reading

Last Updated: Aug 21, 2023