With early diagnosis, Trichnellosis can be treated with prescription drugs. To help prevent infection, efforts must be made to regulate pig farming and inform consumers of the risks of consuming raw or semi-raw meat.

Credit: Carolina K. Smith MD

Credit: Carolina K. Smith MD

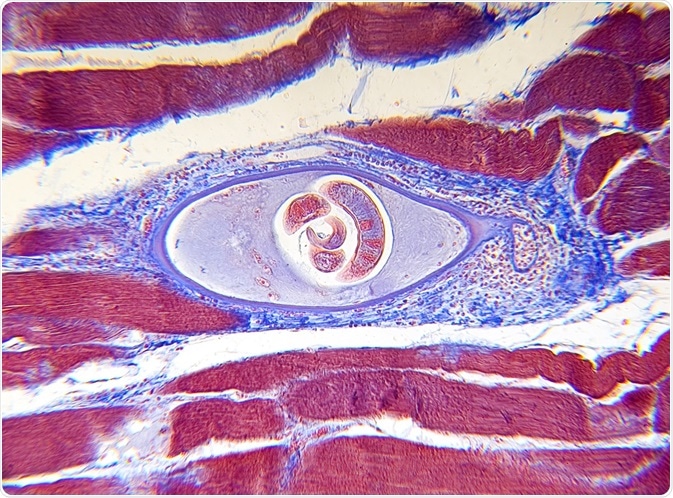

Trichinellosis is a parasitic zoonotic disease with worldwide distribution, closely related to local dietary and cultural habits. It is caused by nematode species of the genus Trichinella and is usually acquired by the ingestion of raw or undercooked meat containing encysted parasitic larvae.

Effective and safe prescription drugs are available for the treatment of both trichinellosis and the symptoms that arise as a consequence of infection. However, the treatment must be administered to the patient before acute stage of the disease runs its course, as drugs are impotent once the larvae are established in the muscle. For this reason, early diagnosis is of the utmost importance.

There are three major principles in the prevention of trichinellosis in humans: consumer education about the risk of consuming raw and semi-raw meat, strict veterinary control over pig farming, as well as control of susceptible animals using standardized artificial digestion methods.

The mainstay of treatment

Drugs used to treat individuals with Trichinella infection include anthelmintics and steroids, in addition to preparations that compensate for electrolyte and protein deficits. Naturally, the principal drugs in the treatment are antihelminthics.

The effectiveness of these drugs depends greatly on the time of administration. Evidence shows that favorable results can be achieved only if the drugs are administered in the early stage of infection. Unfortunately, most affected individuals are diagnosed several weeks after the infection has set in, which means the larvae of Trichinella have already established themselves in the muscle tissue.

Although anthelmintics are given for longer periods of time in more advanced stages of the disease, they usually do not have any effect in preventing or treating chronic, long-term sequelae. Successful attempts to increase their bioavailability by the addition of 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin have been made in a mouse model, but the same results need to be replicated in humans as well.

Corticosteroids are often co-prescribed with anthelmintics, most commonly prednisone. This drug has been shown to be safe and may alleviate symptoms that arise as a result of active parasitic larvae in the tissue. This drug may also prevent the worsening of symptoms and shorten the symptomatic period of the disease.

Pivotal steps in the prevention of trichinellosis

All meat derived from animals that may potentially harbor Trichinella larvae, but cannot be subjected to inspection by an adequate laboratory method, should undergo an inactivation procedure before being distributed for human consumption. This rule is valid for both commercial and noncommercial meat sources.

Three methods are known to reliably inactivate parasitic larvae in meat. One of them is thorough cooking with the aim of reaching a core temperature of 71 °C (159.8 °F) or more for at least one minute, which is recognized by the meat turning gray with its fibers being easily separated.

The other method is freezing, where cuts (or pieces) of meat up to 15 centimeters thick are frozen solid at -15 °C for three weeks or more, and cuts of meat up to 50 centimeters thick for four weeks or more. Irradiation is a third method, used in countries where this method is permitted for packaged, sealed food.

In conclusion, there is an ample amount of evidence that with the use of a diligent reporting and testing system, human trichinellosis can be tracked (and even controlled) to a certain extent. Of course, this requires robust interaction between the public health and veterinary sectors in every country that raises meat for domestic consumption, if we are to minimize the burden of this potentially costly and dangerous disease.

Further Reading

Last Updated: Dec 29, 2022