Skip to

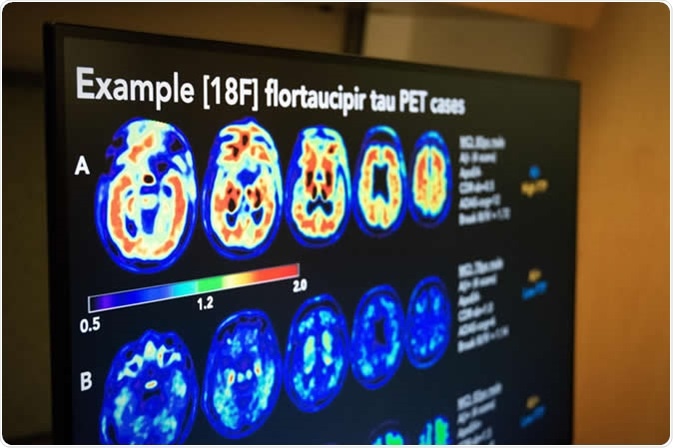

U.S. POINTER randomized controlled trial assessed PET imaging to measure the buildup of amyloid and tau, two proteins whose accumulation in the brain has been linked to Alzheimer's dementia. Malachi Tran, University of California, Berkeley

What is a randomized controlled trial?

A randomized controlled trial (RCT) is one form of scientific experiment, often used in clinical trials, which aims to reduce bias in the interpretation of results by randomly assigning trial participants to one of two or more experimental conditions. In the experiment condition (or arm), participants receive the intervention being tested, whilst the control arm receive either a conventional or placebo treatment.

The two groups will then be followed up for a predetermined time to assess differences between them, either in outcome measurements or measurements of acceptability or safety.

The University of South Florida and Tampa Fire Rescue conducted a a randomized controlled trial to assess the effectiveness of a worksite exercise regimen targeted to reduce the risk of low back injury and disability in firefighters. Photo courtesy of University of South Florida/USF Health

RCTs are considered the standard for determining the effectiveness of a given intervention, as they are the most rigorous method of determining a cause-effect relationship between an intervention and outcome. They have the potential to influence health policy and funding and change clinical practice. RCTs however, are complex and costly, and many publicly-funded trials fail to recruit and retain participants within projected timescales.

One method to improve the design quality and conduct of clinical trials is the use of pilot studies.

What is a pilot study?

A pilot study is a small-scale study conducted in preparation for a larger investigation. The purpose of a pilot study is to increase the likelihood of a successful future RCT by exploring the efficiency, internal validity and fundamentally, the delivery of proposed trials.

To be most effective, they should test the logistics of the proposed study methods under similar circumstances to the planned trial.

Pilot studies should test key elements of the trial, including recruitment and retention strategies, intervention delivery, data collection methods and adherence to the study protocol.

In addition to informing researchers about the feasibility of their future RCT, they play an important role in the eventual implementation and dissemination of the intervention under study by identifying barriers and facilitators.

Finally, pilot studies can provide empirical estimates of treatment effect sizes which in turn can be used to calculate sample sizes for future trials.

ACE pilot study takes cancer rehab to the community, Betty Wood works her lower body at one of the exercise stations during her ACE class at the Don Wheaton Family YMCA. Image Credit: University of Alberta

Optimizing information from pilot studies

Ideally, trial teams together with funding bodies and steering groups should predetermine key progression criteria that should be used to determine whether important targets are met during the pilot phase. This in turn informs decisions as to whether the trial should proceed.

Traditionally, progression criteria have been applied to key areas of risk that could impact on successful trial delivery and have tended to be stop/go in nature, particularly in trials concerning drug development.

However, most clinical trials, particularly large trials conducted across several sites or centers, will make modifications across the study’s lifespan without any formalized pilot processes.

Examples of such adjustments include changing data collection methods, recruitment strategies or even primary outcomes.

These changes may be informed by pilot study results or ongoing monitoring and evaluation during the RCT.

One approach is applying a ‘traffic light system’ to pilot study targets to determine whether a trial could proceed if modifications are applied, with red indicating intractable issues, amber indicating remediable issues and green indicating no issues threatening the trial.

There are three predominant issues for consideration when using pilot study data as a predictor of success in subsequent trials.

Trial recruitment

Successfully recruiting to both time and target is a major concern for triallists and funders, and the largest risk to delivering a successful study.

During the trial planning phase, recruitment targets are based on estimates of the prevalence of the condition under study, the proportion of the target population who can feasibly be screened for eligibility, the proportion screened who meet eligibility criteria, and the projected consent rate.

The purpose of the pilot phase is to either confirm the original estimations or adjust expected recruitment rates as necessary, allowing researchers to impose meaningful minimum recruitment thresholds that are neither conservative nor speculative.

Protocol non-adherence

Assessment of protocol non-adherence may include fidelity to all protocol procedures (including informed consent, data collection or follow-up procedures) but tend to focus on adhering to the intervention under study.

In this context, the extent to which participants receive their allotted intervention (experimental or control) is monitored for ‘cross-over’ and ‘off-protocol intervention’.

When cross-over non-adherence occurs, a participant receives the alternative trial intervention to which they were allocated. In off-protocol non-adherence, participants receive an intervention that differs from either the experimental or control intervention.

Both forms of non-adherence can arise following side effects from the initial intervention, disease progression, or availability of a new treatment approach. Pilot studies can determine reasonable tolerances and inform trial procedures to enhance adherence.

References

- Cook JA, Beard DJ, Cook JR MacLennan GS. The curious case of an internal pilot in a multicentre randomised trial—time for a rethink? Pilot and Feasibility Studies volume 2, Article number: 73 (2016). https://pilotfeasibilitystudies.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40814-016-0113-8

- Kistin C, Silverstein, M. Pilot Studies: A Critical but Potentially Misused Component of Interventional Research. JAMA. 2015 Oct 20; 314(15): 1561–1562. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4917389/

- Koepsell TD, Weiss NS. Epidemiologic Methods. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2003., https://global.oup.com/academic/product/epidemiologic-methods-9780195314465?cc=au&lang=en&

- Pocock, SJ. (1983). Clinical trials. A practical approach. Chicester: John Wiley & Sons., https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/bimj.4710270604

- Sibbald B, Roland M. Understanding controlled trials: Why are randomised controlled trials important? BMJ 1998;316:201. https://www.bmj.com/content/316/7126/201?ijkey=a8035252cd25deabfc7c9edb5764a4897215ce93&keytype2=tf_ipsecsha

- Pilot Studies: Common Uses and Misusehttps://nccih.nih.gov/grants/whatnccihfunds/pilot_studies

- A tutorial on pilot studies: the what, why and how, BMC Medical Research Methodologyvolume 10, Article number: 1 (2010), https://bmcmedresmethodol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2288-10-1

- J Psychiatr Res. 2011 May; 45(5): 626–629. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires., The Role and Interpretation of Pilot Studies in Clinical Research https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3081994/

Further Reading

Last Updated: Sep 18, 2019