Sports-related concussions (SRC) can have a profound impact on affected individuals’ behavior, personality, and mood as well as upon the lives of loved ones, family, and friends.

However, there is very little research on the long-term effects of SRC, and the literature that exists is often quite variable. Mounting evidence suggests that athletes that have sustained repeated head injuries from their sports can increase the risk of developing chronic brain damage leading to potential neurological conditions.

Image Credit: Rocketclips, Inc./Shutterstock.com

What is a Concussion?

A concussion is any temporary injury that occurs in the brain due to a blow or jolt to the head, such as due to whiplash or a sports-related injury.

A concussion is a type of traumatic brain injury (TBI), the commonest, and is usually due to a sudden impact or movement change to the head. This is different from severe TBI in which the brain tissue is usually penetrated, such as by a gunshot wound or cracked skull.

The symptoms of a concussion appear within a few minutes after a head injury but can also take hours post-impact to develop.

Common symptoms include a persistent headache, dizziness, nausea, some level of memory loss, trouble with balance, being confused or dazed, as well as changes in behavior (such as mood swings, emotionality, and demotivation).

Unlike severe TBI, concussions can be managed quite easily and unless the injury is severe, self-management can easily be achieved and patients can usually be discharged from the hospital after serious brain injury has been ruled out.

Most people will recover fully within a few days or a couple of weeks. However, in some cases, the effect of concussion can be felt up to several months after the initial blow, known as post-concussion syndrome.

It has been noted that long-career boxers have shown signs of neurological conditions in later life known as ‘punch drunk syndrome’, as well as dementia and chronic progressive traumatic encephalopathy.

Furthermore, recent studies investigating retired NFL players have shown that there is an association with repeated SRCs and the onset of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) that is not appropriate for their age.

Autopsies on former professional footballers have revealed key brain changes (structural and pathological) including staining positive for phosphorylated tau (a hallmark of Alzheimer’s and other dementias), which again, is not consistent with their age.

The Long-Term Effects of SRC

Recent research has shown that there are two distinct phases in the pathophysiology of concussion/SRC: 1) a primary concussive brain injury & 2) a prolonged ‘neuro-metabolic’ cascade or secondary brain injury.

The initial injury involves shearing and stretching of axons, and the neuro-metabolic cascade induced a state of neuronal exhaustion and toxicity that can persist for some time.

Repeated concussions can worsen the situation as the secondary neuro-metabolic cascade may not have fully recovered, leading to a heightened metabolic imbalance and subsequent energy crisis within the brain. It is thought that this may be the causative factor in the longer-term effects of SRCs.

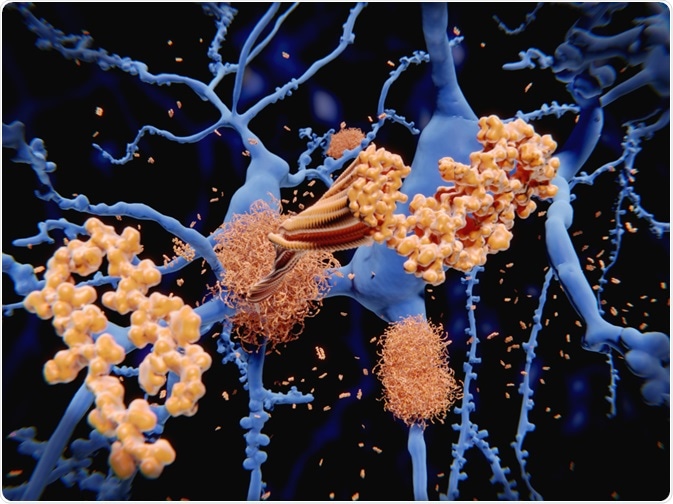

Some of the confirmed long-term effects as a result of repetitive SRC neuro-metabolic cascade include the development of tau-pathology, axonal degeneration, and impaired oxidative capacity of mitochondria leading to cell death (cortical thinning).

The reduced neuro-metabolic function can then itself lead to the build-up of pathogenic toxic protein aggregates such as amyloid-beta and tau, the two hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease and MCI.

Image Credit: Juan Gaertner/Shutterstock.com

The breakdown of axons (networks between brain regions) can leads to disrupted neural networks clinically manifesting as reduced cognitive function and slowed reaction times (as in the case of punch-drunk syndrome).

In addition to cognitive changes as a result of protein aggregation build-up and degeneration of axons between brain regions, there are some other key changes to other brain regions involved in movement.

For example, post-mortem analysis from boxers who have suffered multiple head injuries showed evidence of cerebellar scarring and the degeneration of the substantia nigra and locus caeruleus. Degeneration of the substantia nigra is implicated in Parkinson’s disease, the famous boxer Mohammad Ali also suffered from Parkinson’s disease.

Some of the other known long-term changes as a result of repetitive SRCs include changes to behavior and personality clinically manifested as depression (increased risk by 3-fold), aggression, impaired judgment, and agitation.

There is also a strong association between concussion in both civilian and military personnel and with suicide attempts. Those that have had multiple head injuries were more likely to suffer from MCI and dementia.

It is important to note that not all the literature finds such strong associations between SRC and later life changes. The discrepancies may likely be related to factors such as the severity of SRC, the number of SRCs (or interval between SRCs), sex, lifestyle, genetics, and the environment that may predispose certain individuals more to the ill-effects described.

Nonetheless, repeated SRCs do seem to be associated with at least subtle cognitive, behavioral and pathological changes that may be exacerbated with a history of repeated SRCs or illness later in life, narrowing the threshold for clinically relevant changes.

In summary, the long-term effects of SRC are still largely poorly understood with a whole plethora of contradictory findings, however, there are strong associations with repeated SRCs (or severity) with major changes in later life, including cognitive impairment/dementia, motor dysfunction, toxic protein aggregation in the brain, neuronal degeneration in key brain areas as well as increased risk of depression and suicide attempts.

The mechanisms behind these associations may be due to a prolonged metabolic dysfunction in the brain that leads to a state of neuronal exhaustion where repeated injuries infringe on recovery, though more research is required to understand these associations fully to prevent them.

Further Reading

Last Updated: May 4, 2020