Introduction

Cause and Symptoms

Bacillus anthracis

Epidemiology

Diagnosis and Treatment

Biological Warfare Agent

References

Further Reading

Anthrax is a zoonotic bacterial disease caused by Bacillus anthracis, a gram-positive, spore-forming bacterium commonly found in the soil of endemic areas. It is primarily a disease of herbivorous wildlife and livestock that occasionally infects other carnivores or omnivores, including humans.

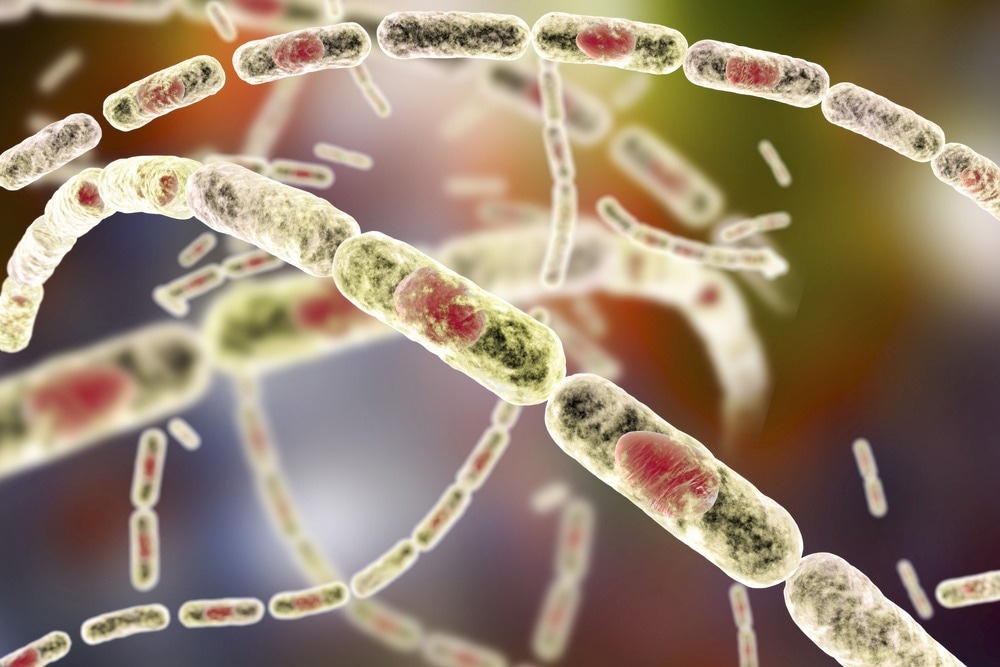

Anthrax. Image Credit: Kateryna Kon/Shutterstock.com

Humans contract the disease by unintentional contact with infected animals or animal products. Infections in humans have a significant mortality rate if not recognized and treated promptly.

B. anthracis is identified as a possible bioweapon in addition to naturally acquired forms of anthrax, and the risk of obtaining anthrax from laboratory-produced B. anthracis spores highlights the necessity of anthrax surveillance, prevention, and control in anthrax-endemic nations.

Cause and symptoms

The causative agent for anthrax is B. anthracis, which is an aerobic, spore-forming, and rod-shaped bacterium.

The disease has three forms: cutaneous, inhalational, and gastrointestinal, which arise when endospores enter the body by skin cracks, inhalation, or ingestion, respectively. Human anthrax is cutaneous in 95% of cases and inhalational in 5%. Gastrointestinal anthrax is extremely rare, occurring in fewer than 1% of all cases. Anthrax meningitis is an uncommon consequence of any of the disease's three forms.

The pulmonary infection has a 1–6-day incubation time and is initially characterized by flu-like symptoms in humans, delaying identification in the early phase before rapidly deteriorating to cytokine-independent shock-like syndrome with meningitis, multiple organ failure, cardiac arrest, and death.

Symptoms of gastrointestinal anthrax include nausea, loss of appetite, bloody diarrhea, and fever with stomach pain. Humans contract the disease by unintentional contact with diseased animals or animal products, or through intake or handling of infected animal meat. Anthrax can be passed from animal to animal or human to human.

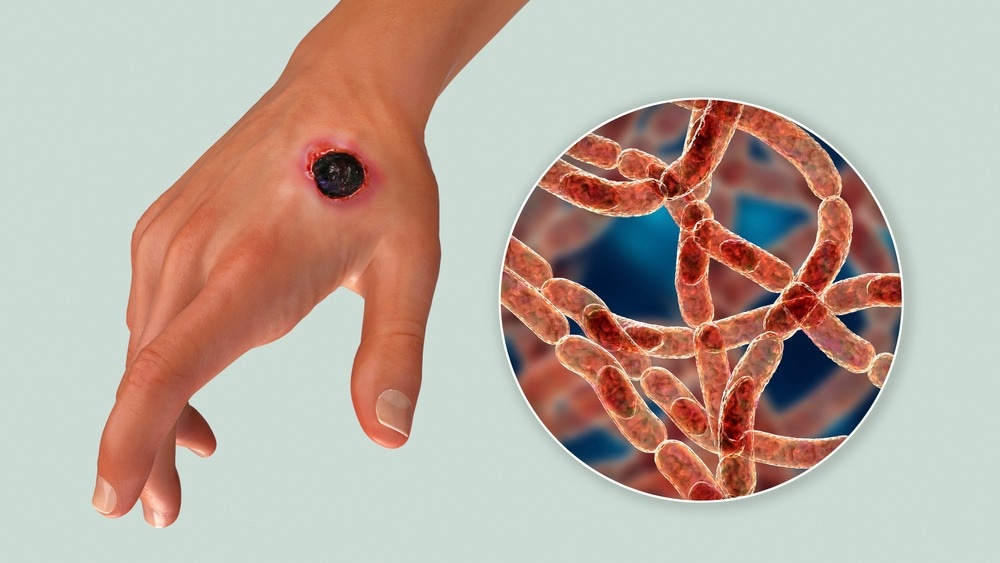

Cutaneous anthrax occurs when spores enter the body through breaks in exposed skin. The spores germinate locally or in regional lymph nodes within macrophages, and vegetative forms are expelled. The incubation period ranges from one to twelve days.

The first skin lesion is a painless or pruritic papule with a disproportionate quantity of edema that evolves into a vesicular form (1–2 cm). Fever and regional lymphadenopathy are possible side effects. The vesicle then ruptures, resulting in an ulcer and black eschar that sloughs off in 2 to 3 weeks. Purulence is only seen in nonanthrax secondary infections. Airway impairment may result from edema combined with a face or neck infection.

Bacillus anthracis

B. anthracis occurs in two forms: vegetative cells (which live within the host) and spores, which live in the soil or environment. It has a width of 1-1.2 µm, with a length of 3-5 µm and appears to have a chain-like structure under a microscope. Despite being an aerobic bacterium, B. anthracis may thrive in an anaerobic environment due to its sporulation ability. It can live as spores for several years in soil, air, and water.

Spores are unaffected by hostile environments and are resistant to high temperatures, pressure, pH, chemicals, UV, and nutrient deprivation. B. anthracis is commonly found in the soil in endospore form, where it can survive for decades. B. anthracis has two key virulence factors: a poly—D-glutamic acid capsule and a tripartite toxin. Pathogenic B. anthracis bacteria form a capsule that imitates the host's immune system by concealing the germs from macrophages.

Epidemiology

B. anthracis spores can live in soil for many years and are found all over the world, even though the infection is only found in specific regions. Anthrax is most prevalent in agricultural areas of Central and South America, Sub-Saharan Africa, Central and Southwest Asia, and Southern and Eastern Europe. Although outbreaks of human anthrax continue to occur in livestock and wild herbivores in the United States, Canada, and Western Europe, human anthrax is now uncommon in these locations.

Anthrax. Image Credit: Kateryna Kon/Shuttestock.com

Diagnosis and treatment

According to the CDC, a confirmed anthrax case is clinically consistent with the isolation of B. anthracis or has at least two positive supporting tests using serologic or other methods. The most common method of diagnosis is routine culture with confirmation by immunohistochemical staining or real-time PCR.

Given the possible severity of anthrax infection, the earliest suspicion of disease must prompt antibiotic treatment until the diagnosis is confirmed. Although antibiotics are crucial in the treatment of B. anthracis, their effectiveness may be related to factors other than bacterial clearance. Animal immunization is a critical strategy for preventing and controlling anthrax in animals and, as a result, preventing human infection.

Immunotherapy has remained one of the most popular therapeutic options for individuals with fulminant-stage pulmonary or gastrointestinal anthrax. Passive immunization with therapeutic antibodies becomes one of the most important pillars of prophylactic emergency treatment in the case of exposure to antibiotic-resistant anthrax spores, as expected in deliberate bioterror attacks, or the delayed start of standard post-exposure therapy when toxemia has set in.

B. anthracis is resistant to a wide range of antimicrobial drugs, including first-generation cephalosporins. Third-generation cephalosporins and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole are not effective against the bacterium. In all situations, an antimicrobial susceptibility test should be performed, and therapy should be changed accordingly.

Biological warfare agent

Anthrax has had the potential to be used as a biological warfare agent since World War II when it was investigated along with numerous other infectious agents for use as biological weapons. Low visibility, great potency, relatively easy delivery, accessibility, and the capacity to generate spores that are resistant to drying are all characteristics of anthrax that make it a good biological weapon. This has gained it the infamous reputation of hazardous 'Category A' infection.

Although anthrax infection is rare, the possibility of massive epidemics remains, whether due to bioterrorism or injectional drug usage. More research is required to define the mechanisms driving later-stage anthrax, as well as to design and test effective management measures that may be applied on a large basis. Steps to prevent bioterrorism should be designed and implemented.

References

- Manish, M., Verma, S., Kandari, D., Kulshreshtha, P., Singh, S., & Bhatnagar, R. (2020). Anthrax prevention through vaccine and post-exposure therapy. Expert opinion on biological therapy, 20(12), 1405–1425. https://doi.org/10.1080/14712598.2020.1801626

- Hendricks, K., Vieira, R. A., & Marston, K. C. (2019). Anthrax. CDC. Available at: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2020/travel-related-infectious-diseases/anthrax#:~:

- Vieira, A. R., Salzer, J. S., Traxler, R. M., Hendricks, K. A., Kadzik, M. E., Marston, C. K., Kolton, C. B., Stoddard, R. A., Hoffmaster, A. R., Bower, W. A., & Walke, H. T. (2017). Enhancing Surveillance and Diagnostics in Anthrax-Endemic Countries. Emerging infectious diseases, 23(13), S147–S153. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2313.170431

- Goel A. K. (2015). Anthrax: A disease of biowarfare and public health importance. World journal of clinical cases, 3(1), 20–33. https://doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v3.i1.20

- Moayeri, M., Leppla, S. H., Vrentas, C., Pomerantsev, A. P., & Liu, S. (2015). Anthrax Pathogenesis. Annual review of microbiology, 69, 185–208. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-micro-091014-104523

- Sweeney, D. A., Hicks, C. W., Cui, X., Li, Y., & Eichacker, P. Q. (2011). Anthrax infection. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine, 184(12), 1333–1341. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201102-0209CI

- Kamal, S. M., Rashid, A. K., Bakar, M. A., & Ahad, M. A. (2011). Anthrax: an update. Asian Pacific journal of tropical biomedicine, 1(6), 496–501. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2221-1691(11)60109-3

Further Reading

Last Updated: Oct 12, 2022