Apert syndrome (AS) is a genetic disorder that involves deformities in the skull, face, and limbs. Also known as acrocephalosyndactyly, it is characterized by craniosynostosis (premature union of coronal sutures), midfacial hypoplasia, and syndactyly. Eugene Apert, a French physician, originally described the syndrome in 1906 when he documented nine persons with comparable facial and extremities traits.

Image Credit: ibreakstock/Shutterstock.com

Causes and symptoms

Apert syndrome's exact cause is unknown. According to experts, it's the result of a hereditary mutation in a gene called "fibroblast growth factor receptor 2," or FGFR2, that happens early in pregnancy. FGFR2 is involved in bone formation. Its disruption could therefore result in physical features of Apert syndrome as craniosynostosis and syndactyly.

Similar craniofacial syndromes involving the FGFR2 gene include Crouzon syndrome, Pfeiffer syndrome, and Jackson-Weiss syndrome. No known food, drug, or activity during pregnancy has been identified as a causative agent of Apert syndrome.

Apert syndrome is caused by a novel mutation in the FGFR2 gene in up to 95% of patients. For unexplained reasons, these new mutations appear to develop at random (sporadically). AS is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern in a small percentage of cases. When just one copy of a mutation is required to induce disease, it is known as a dominant genetic condition. Each pregnancy has a 50% chance of transferring the mutation from an affected parent to an offspring.

Physical hallmarks of the syndrome include a tall skull and high prominent forehead, underdeveloped upper jaw, fused fingers and toes, prominent bulging eyes, and cleft palate. Other symptoms including vision problems (caused by an imbalance of the eye muscles), slower mental development due to the abnormal growth of the skull, recurrent ear infections (which can cause hearing loss), and difficulty breathing due to small airway passages are also observed.

In most affected individuals, the sutures between the bones that create the forehead and the upper sides of the skull close prematurely. From birth, this causes the head to seem pointed at the top (acrocephaly). Furthermore, the back of the skull may appear flattened, with a broad and high forehead. A big, late-closing "soft spot" on the skull is possible. Hydrocephalus is a condition in which cerebrospinal fluid collects abnormally in the cavities of the brain, which can put a strain on the brain.

Genetics of apert syndrome

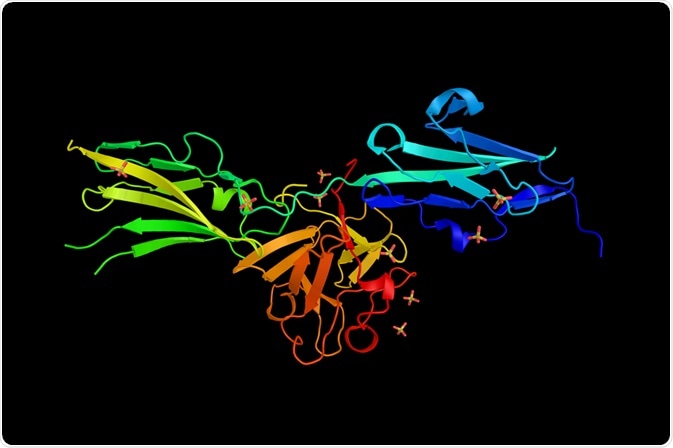

FGFs are a class of signaling molecules that govern cell proliferation, differentiation, and migration via a variety of complex pathways. There are at least 22 identified FGFs. They work by activating the fibroblast growth factor receptors (FGFRs), which are a family of four tyrosine kinase receptors that are transmembrane.

Apert syndrome is caused by a mutation in the FGFR2 gene, which is located on chromosome 10q25–10q26. It is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner and contains mutations in two neighboring FGFR2 amino acids, Ser252 and Pro253. During growth and bone development, the FGFR2 gene is responsible for the development and union of the skull sutures.

Epidemiology

Apert syndrome is a rare condition that affects one out of every 65,000 to 200,000 babies. Both men and women are at equal risk for the syndrome. Occasionally, it has been linked to the father's increasing age. Within the same family, the syndrome exhibits complete penetrance with varying expressivity. It can result in phenotypically untouched to severe abnormalities.

Since the illness was first identified in 1894 and 1906, over 300 cases have been reported. The highest incidence of AS is recorded in the Asian population.

Diagnosis and treatment

Apert syndrome is most commonly diagnosed at birth or during childhood. Clinical assessment and a variety of specialized tests are used to diagnose a person. Physical characteristics such as syndactyly or facial abnormalities can be recognized.

Imaging, such as computed tomography (CT) scan or an MRI, can reveal skeletal abnormalities and congenital heart problems. Hearing loss can be detected during a newborn hearing screening. Individuals may also be tested for mutations in the FGFR2 gene, which can lead to an Apert syndrome genetic diagnosis.

The symptoms of the syndrome can be discovered before birth in some cases. This would be done via prenatal ultrasound (2D or 3D) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). An ultrasound is a non-invasive treatment that allows you to see a picture of your unborn child. Differences in skull form, facial anomalies, and syndactyly can all be detected using this method. Fetal MRI offers more information about the fetal brain than ultrasonography.

The treatment for Apert syndrome differs depending on whatever symptoms the patient exhibits. AS is treated with symptomatic and supportive therapy. Early surgery (within 2 to 4 months of life) to repair craniosynostosis may be advised in such circumstances. Corrective and reconstructive surgery may be recommended to help correct craniofacial abnormalities.

Hearing aids may be advantageous for certain people who have hearing loss. Children with Apert syndrome may benefit from early intervention to help them realize their full potential. Physical therapy, occupational therapy, and special education services may be effective.

Affected individuals and their families should seek genetic counseling. The causes of the syndrome can be explained by a genetic counselor. They can also talk about the possibility of having more children with Apert syndrome. It is also necessary to provide psychosocial support to the entire family.

Future scope in therapies

Identification of phenotypic variants, in addition to proteomic and genetic modification, is critical. It will allow targeted therapies employing either gene or pharmaceutical approaches to target these variants and potential lifestyle changes that may modify the outcome.

Many of the molecular traits revealed in this syndrome are yet inexplicable, necessitating extensive research. Apert syndrome is still an unanswered topic of investigation in congenital illnesses. Although several studies have reported on different aspects of the condition, genetic heterogeneity differs from case to case.

Thus, suspected instances must be thoroughly explored using clinical and molecular methods. Many of the clinical symptoms seen are currently unexplained, and as a result, there is no specific treatment strategy that can improve the patient's quality of life.

References:

- Al-Namnam, N. M., Jayash, S. N., Hariri, F., Rahman, Z., & Alshawsh, M. A. (2021). Insights and future directions of potential genetic therapy for Apert syndrome: A systematic review. Gene therapy, 10.1038/s41434-021-00238-w. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41434-021-00238-w

- Conrady CD, Patel BC, Sharma S. Apert Syndrome. [Updated 2021 Aug 11]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK518993/

- Wenger TL, Hing AV, Evans KN. (2019). Apert Syndrome. In: GeneReviews®. University of Washington, Seattle, Seattle (WA). PMID: 31145570.

- Das, S., & Munshi, A. (2018). Research advances in Apert syndrome. Journal of oral biology and craniofacial research, 8(3), 194–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobcr.2017.05.006

- Apert Syndrome. [online] National Organization for Rare Disorders. Available at: https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/apert-syndrome/

- Apert Syndrome. [online] Boston Children’s Hospital. Available at: https://www.childrenshospital.org/conditions-and-treatments/conditions/a/apert-syndrome

Further Reading

Last Updated: Nov 19, 2021