Introduction

Antigens

Pathophysiology of autoimmune disorders

Diagnosis of autoimmune disorders

Autoantibody tests

Examples of autoimmune disorders

References

Further reading

Introduction

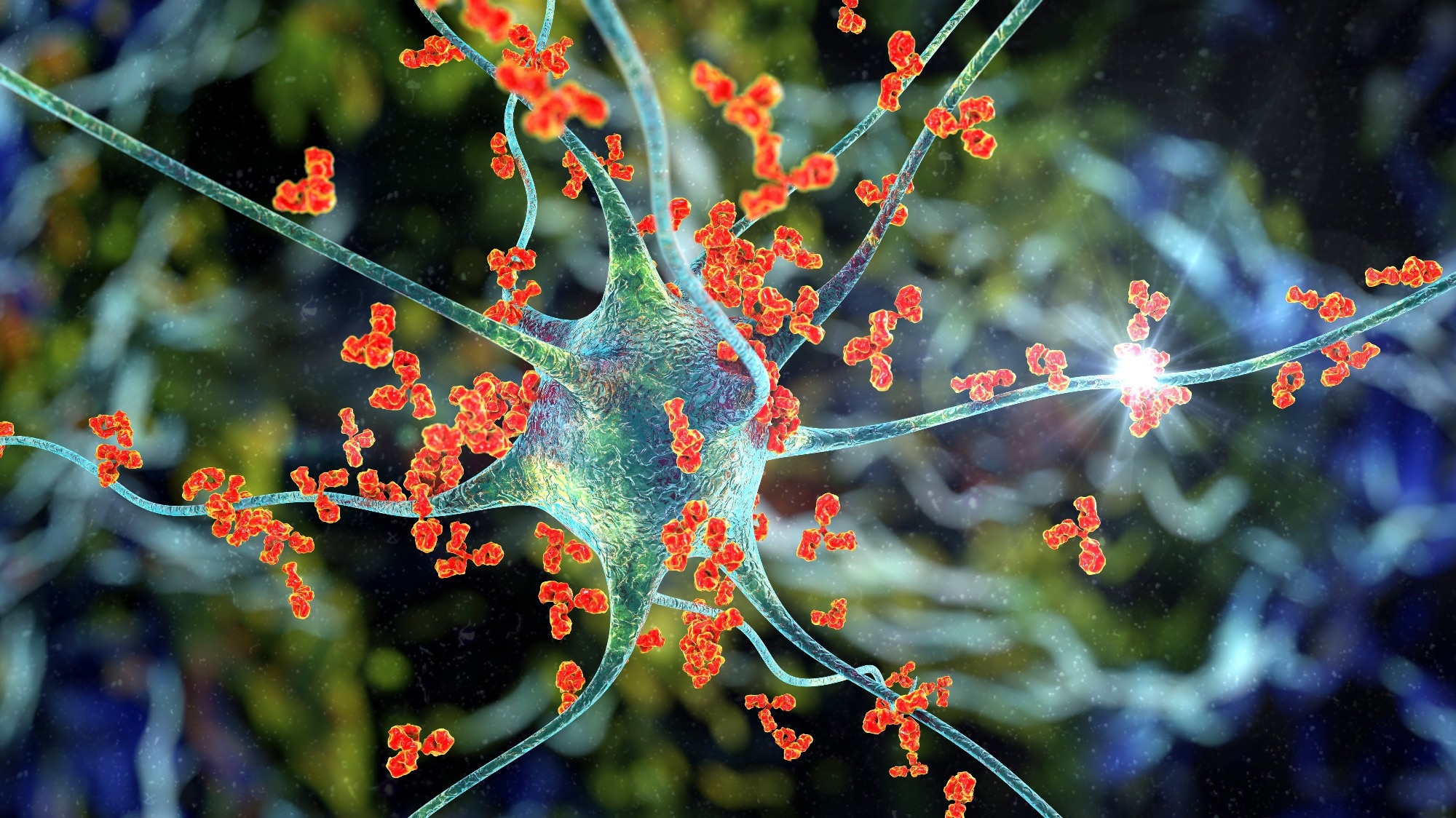

The term autoimmunity refers to the failure of the human body's immune system to recognize its cells and tissues as "self." In contrast, humoral and cell-mediated immune responses by B lymphocytes and T lymphocytes, respectively, are launched against the normal components of an individual (autoantigens) as if they were foreign or invading bodies.

In other words, autoimmunity refers to an immune reaction that is directed against an individual's own tissue that may cause tissue damage and cause disease. Autoimmune diseases develop when the auto-reactive B lymphocytes (autoantibodies) and T lymphocytes described above cause pathological and/or functional damage to the organ/tissue containing the target autoantigen(s). Thus, in autoimmune diseases, the auto-reactive lymphocytes are the actual cause of the disease rather than a harmless accompaniment.

Image Credit: Kateryna Kon / Shutterstock

Image Credit: Kateryna Kon / Shutterstock

Antigens

An antigen is a substance that activates the immune system to produce a specific response that reacts against the antigen that activated the immune response and is usually foreign to the body, such as an infectious agent. Antigens that recognize self-antigens as 'non-self' are referred to as autoantigens, and the antibodies (from B lymphocytes) and T lymphocytes that recognize the autoantigens are called autoantibodies and autoreactive T cells, respectively.

In previous years, a misconception existed that the body was not capable of recognizing "self" antigens. At the start of the twentieth century, Paul Ehrlich described the concept of "horror autotoxicus," which referred to how a normal body would not create an immune attack against its own tissue. Therefore, such responses were considered abnormal and a sign of disease. However, today, it is well understood that autoimmunity is a key part of the vertebrate immune system that is usually kept in check by an immunological tolerance of antigens that are "self."

Pathophysiology of autoimmune disorders

The main functions of the immune system are to protect the body from infectious agents and other foreign invaders. The immune system is composed of special cells and organs that, together, mount an immune attack against foreign chemicals, viruses, bacteria, or pollen.

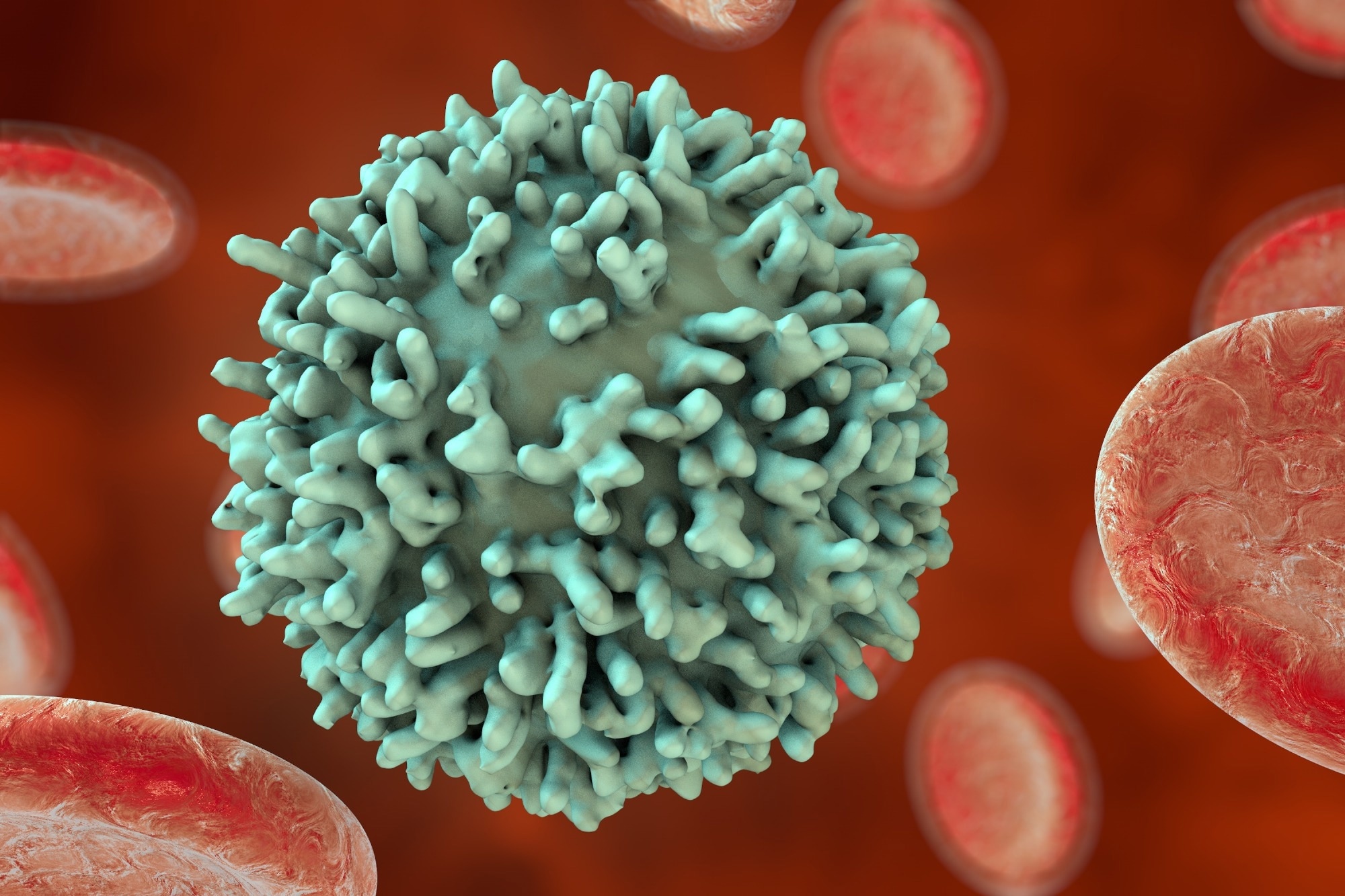

B lymphocytes develop into plasma cells and produce antibodies to combat the infectious invaders or antigens that trigger immune responses. For the immune system to function appropriately, it must be able to distinguish cells that are "self" from substances that are non-self or foreign, and when the immune system fails to do this, it instead produces antibodies directed toward the body's own tissues, auto-antibodies.

Image Credit: Kateryna Kon / Shutterstock

Image Credit: Kateryna Kon / Shutterstock

B lymphocytes are produced and mature in the bone marrow as part of the normal process of B cell maturation, and a few B lymphocytes may develop immunoglobulin receptors that are reactive to self-antigens. Therefore, they can release antibodies that react with self-antigens. To prevent the development of autoimmune diseases, autoreactive B lymphocytes must be eliminated before they can produce harmful reactions.

The process of removal of autoreactive lymphocytes is called tolerance and involves the actual death or functional inactivation of autoreactive lymphocytes. Likewise, T lymphocytes arise in the bone marrow but mature in and undergo tolerization in the thymus gland.

The presence of autoimmune diseases indicates inefficient tolerization avoidance of apoptotic elimination, immune escape of autoreactive lymphocytes, and reversal of an anergic state. In autoimmune diseases, autoreactive T and B lymphocytes emerge from primary lymphoid tissues, escape the regulatory mechanisms that normally delete them or keep them in check, and make their way to secondary lymphoid tissues where activation of autoreactive cells occurs.

Besides these mechanisms, infectious agents with antigenic sites similar to self-antigens may cause autoimmune diseases with the breaking of tolerance for those self-antigens. Rheumatic fever is caused by this immune mechanism.

In the spleen, lymph nodes, and blood, many immune reactions are initiated that regulate immune cell function and the population of the lymphoid system. Altered function and imbalance of immune regulatory cells may predispose to the development of autoimmune disorders. For example, reduced levels of transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) due to macrophage inhibition and elevated levels of interferon-gamma production by CD4 Th1 lymphocytes may activate autoreactive B or T lymphocytes, respectively.

The effector mechanisms appear to be no different from those used to combat exogenous agents (invading viruses, bacteria, or other pathogens) and include soluble products such as antibodies (humoral immunity), as well as direct cell-to-cell interaction leading to specific cell-lysis (cell-mediated immunity).

Taken together, autoimmune diseases can be considered a manifestation of immune dysregulation. In normal circumstances, a healthy immune system is tolerant of the tissue constituents of the host but intolerant of nonhosts (or "non-self") matter, whereas, in autoimmunity, the immune system mounts responses against tissue constituents of the host organism (auto-antigens).

Diagnosis of autoimmune disorders

In autoimmune diseases, auto-reactive lymphocytes expand polyclonally (forming multiple types of autoreactive lymphocytes) since the mechanisms that normally keep them at bay fail. The lymphocytes that expand have different antigen receptors on their surface, recognizing different targets (called epitopes) within a single protein or a group of proteins.

Immunization studies have indicated that some autoantibody responses may arise sequentially, a process termed epitope spreading in mice; however, whether this mechanism applies to humans needs further investigation.

Autoantibodies have been the tool used by clinical laboratories to diagnose and monitor autoimmunity. The molecular spectrum of autoantigenic targets, together with their exquisite antigenic specificity, has made autoantibodies valuable reagents in molecular and cellular biology. In both organ-specific and systemic autoimmune diseases, in vivo deposition of autoantibody in tissues and organs has clinical significance, as it indicates sites of inflammation and possible pathological lesions.

Autoantibody tests

The most commonly performed autoantibody test is immunofluorescence to diagnose particular antibodies (e.g., anti-acetylcholine receptor autoantibodies in myasthenia gravis and anti-thyroid stimulating hormone receptor autoantibodies in Graves' disease).

Other tests performed for the diagnosis of autoimmune disorders include enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA), immunoblotting, and immunoprecipitation.

Image Credit: AnaLysiSStudiO / Shutterstock

Image Credit: AnaLysiSStudiO / Shutterstock

In indirect immunofluorescence (IIF), autoantibodies against chromatin and deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) can be used to identify the cell nucleus.

Other nuclear structures, such as the nuclear lamina, which underlies the nuclear envelope, can be identified by anti-lamin autoantibodies as a ring-like fluorescence around the nucleus. Anti-fibrillarin autoantibodies can identify fibrillarin, and autoantibodies to ribonucleic acid (RNA) polymerase I, although rare, have proven to be a valuable marker for the fibrillar center of the nucleolus.

Examples of autoimmune disorders

Examples of autoimmune disorders include insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), Hashimoto's thyroiditis, Graves' disease of the thyroid, Sjogren's syndrome, Churg-Strauss Syndrome, Coeliac disease, rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura.

Diseases associated with autoantibodies can be divided into two broad groups: multisystem autoimmune diseases, in which autoantibodies react with common cellular components that appear to bear little relationship to the clinical syndrome, and organ-specific autoimmune diseases, in which autoantibodies can react with autoantigens from a particular organ or tissue.

SLE is representative of multisystem autoimmunity, in which disease processes may involve several body organs with the formation of anti-dsDNA autoantibodies causing systemic inflammation. On the contrary, IDDM is illustrative of organ-specific autoimmunity, which is more restrictive, targeting perhaps a single organ such as the pancreas.

In both organ-specific and systemic autoimmune-type of diseases, in vivo deposition of autoantibodies in tissues and organs has clinical significance, as it indicates sites of inflammation and possible pathological lesions and, therefore, can be diagnosed by autoantibodies.

Several features of the relationship between autoantibody specificity and diagnostic significance within multisystem autoimmune diseases bear consideration. Autoantigens in these diseases are components of macromolecular structures such as the nucleosome of chromatin and the small nuclear ribonucleoprotein (snRNP) particles of the spliceosome, among others. Autoantibodies to different components of the same macromolecular complex can be diagnostic for different clinical disorders.

For example, the core proteins and snRNPs that are antigenic targets in the anti-Smith antigen (Sm) response in SLE, are different from the snRNP proteins that are targets of the antinuclear RNP (nRNP) response in mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD). It has also been shown that particular autoantibody responses are consistently associated with one another. The anti-Sm response, which is diagnostic of SLE, is commonly associated with the anti-nRNP response, but when the anti-nRNP response occurs in the absence of the anti-Sm response it can support the diagnosis of MCTD.

The anti-SS-A/Ro response frequently occurs alone in SLE, but the anti-SS-B/La response in Sjogren's syndrome is almost always associated with the anti-SS-A/Ro response. Similarly, the antichromatin response occurs alone in drug-induced lupus but is often associated with the anti-double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) response in idiopathic SLE.

In some cases, the grouping of autoantibody specificities, such as the preponderance of antinuclear (ANA) autoantibodies in scleroderma, provides intriguing but as yet little understood relationships with clinical diagnosis. Unlike SLE, where a single patient may have multiple autoantibody specificities to several unrelated nuclear autoantigens (e.g., DNA, Sm, SS-A/Ro), scleroderma patients are less likely to have multiple autoantibody specificities to nucleolar autoantigens that are unrelated at the macromolecular level. Further, homogeneous staining of the nucleus is more likely in SLE, whereas nucleolar staining has been found more often in the serum of patients with scleroderma.

Taken together, the spectrum of autoimmune disorders comprises tissue or organ-specific or systemic immune responses elicited by autoreactive B and T lymphocytes as a result of immune dysregulation and attack against the host/self.

Autoimmunity & How to AIM to be informed about chronic illness | Darshi Shah | TEDxUCIrvine

References

Further Reading

Last Updated: Dec 21, 2022