Introduction

Endemic treponemal diseases

Cause and symptoms

Epidemiology

Diagnosis and treatment

References

Further reading

Infections caused by the treponema pallidum subspecies endemicum are described as bejel, an endemic treponematosis. In Europe, bejel was eradicated in the twentieth century, though it was widespread in the sixteenth century. Bejel is still prevalent in certain parts of the world, particularly in arid and hot climates.

The World Health Organization (WHO) classifies Bejel infection as a non-venereal tropical disease that is often overlooked.

Bejel is very similar to syphilis, though, unlike syphilis, it is not sexually transmitted. Image Credit: Nau Nau/Shutterstock

Bejel is very similar to syphilis, though, unlike syphilis, it is not sexually transmitted. Image Credit: Nau Nau/Shutterstock

Endemic treponemal diseases

Along with bejel, yaws and pinta are also categorized as endemic treponemal diseases. The most common of them all is yaws. In the last 3 years, 14 countries reported yaws cases to the WHO, including the Solomon Islands, Papua New Guinea, and Ghana, which each reported over 20,000 cases in 2010 and 2011. Pinta may still be endemic in distant parts of Mexico including states of Oaxaca, Michoacan, and Chiapas, where it was prevalent in the 1980s.

Pinta is a noninvasive disorder that causes just local skin lesions. Yaws is a cutaneous condition. Yaws skin ulcers are often circular, with granulating tissue in the center and raised margins. The pinta primary lesion, on the other hand, is an itchy, scaly papule or plaque that grows to a diameter of more than 10 cm but does not ulcerate.

Cause and symptoms

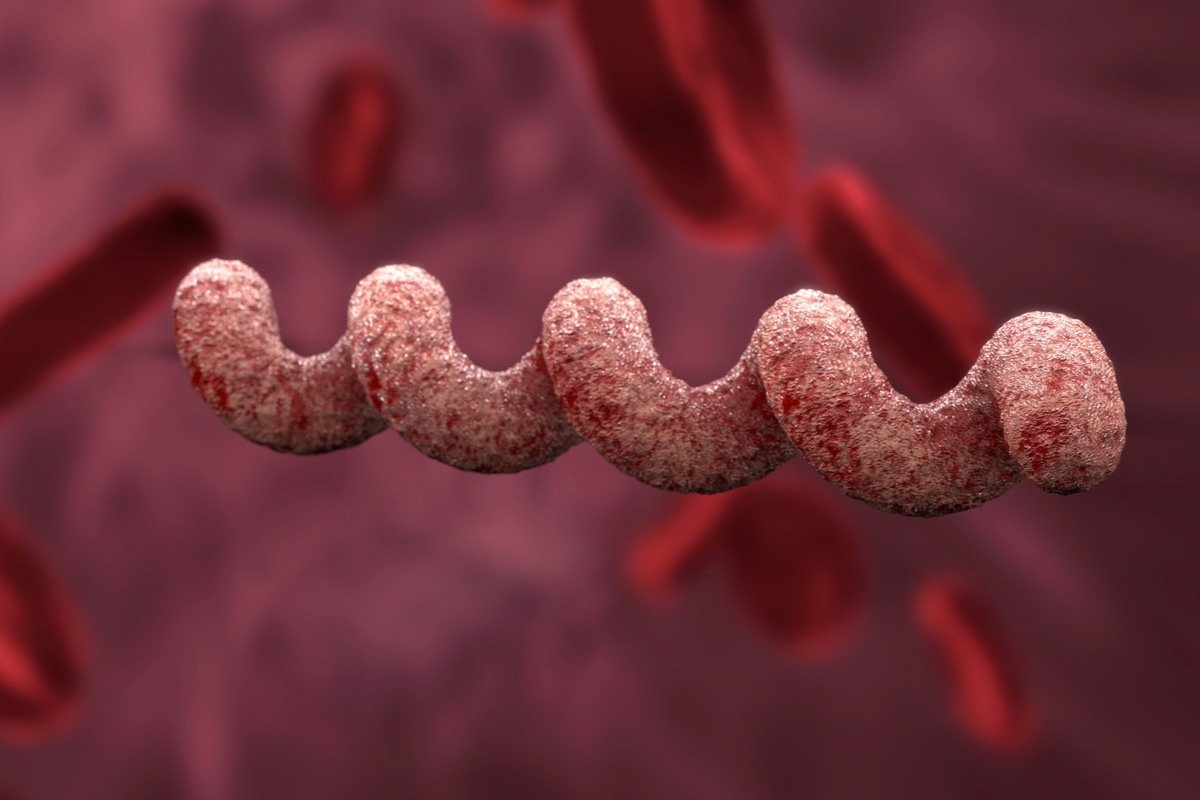

Treponematoses are infections caused by Treponema species spirochetal organisms. Both syphilis (Treponema pallidum ssp. pallidum) and the so-called nonvenereal or endemic treponematoses are caused by these microorganisms (ETs). Bejel, yaws, and pinta are among them.

Bejel is classified as a semimucosal disease. The early onset of lesions characterizes bejel (in primary and secondary stages). Primary lesions in the oral cavity sometimes go undiagnosed or develop as small, painless ulcers. Mucosal lesions and plaques in the oropharynx and on the lips are seen in the secondary stage.

According to an examination of 3,507 cases in Iraq, the most prevalent secondary-stage signs of bejel are mucosal eroding lesions and plaques in the oropharynx and lips, which can extend locally to the larynx, causing hoarseness.

Treponema pallidum bacteria. Image Credit: bekirevren/Shutterstock

Treponema pallidum bacteria. Image Credit: bekirevren/Shutterstock

Both bejel and syphilis can present with mucosal lesions, papules at the oral commissures, and intertriginous condyloma lata, which should always be considered in the differential diagnosis of bejel. It is most commonly found in youngsters under the age of 15 and is linked to dry, arid surroundings.

In addition, lesions on the nipples of nursing women and in the genital regions of patients have also been reported. Infections are generally thought to be transmitted by direct contact with secretions from lesions or via fomites, though the transmission path has not been fully described.

If left untreated, bejel develops into a late-stage disease with gummatous lesions. Gummatous nodules on the skin can develop into infiltrating, unnaturally pigmented lesions. Gummata affecting the nasopharynx can cause destructive rhinopharyngitis (gangosa). Gummatous lesions in tertiary bejel may resemble leishmaniasis, deep fungal infection, cutaneous tuberculosis, or mycobacterial infection symptoms. Gumma is not clinically or histologically identifiable, although the presence of plasmocytes is suggestive.

Cardiovascular and neurological manifestations do not occur in tertiary bejel, unlike venereal syphilis. Osteoperiostitis is a slow-progressing condition that manifests as diffuse cortical thickening followed by bone distortion in bejel. This primarily affects the long bones including, the forearm, tibia, or fibula.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of bejel is usually common in areas with a dry climatic condition. Because the bejel treponeme prefers moist regions of the body, such as the lips, the disease spreads by direct touch or indirect contact. With endemic reports from 22 nations in Africa's south and Sahel regions, along with the Middle East, the epidemiology of bejel is poorly understood.

Furthermore, bejel from the Republic of Senegal, Mali, and Pakistan has been detected in Canada and France. It has also been described in Saudi Arabia, Iraq, and Syria. In 1995, three cases of bejel were reported in southeast Turkey (where the disease was thought to be eradicated). A case report from southwest Iran was also documented in 2012.

Diagnosis and treatment

Clinical signs do not often clearly identify the condition, and serological tests are unable to distinguish this infection from infections caused by other uncultivable human pathogenic treponemes, making the diagnosis of bejel extremely challenging. With the development of molecular techniques, all treponeme pathogens may now be identified using PCR schemes or DNA-sequencing-based methods.

However, reliable diagnosis remains difficult in resource-poor nations with high syphilis incidence. Given the significant epidemiological overlap of venereal syphilis and endemic treponemal diseases (including yaws and bejel), a definitive diagnosis should be made.

Since 1948, when long-acting penicillin (single intramuscular injection) was shown to be efficacious against endemic treponematoses, it has been the standard of care and treatment for bejel and other endemic treponemal diseases. Patients should be checked 2–4 weeks after receiving antibiotic treatment. Within 24 hours of treatment, the lesions of bejel become noninfectious, and complete healing of the primary and secondary lesions occurs in most instances within 2–4 weeks.

Long-acting penicillin is the current standard of care and treatment for bejel. Image Credit: shtiel/Shutterstock

Long-acting penicillin is the current standard of care and treatment for bejel. Image Credit: shtiel/Shutterstock

References

- Kawahata, T., Kojima, Y., Furubayashi, K., Shinohara, K., Shimizu, T., Komano, J., Mori, H., & Motomura, K. (2019). Bejel, a Nonvenereal Treponematosis, among Men Who Have Sex with Men, Japan. Emerging infectious diseases, 25(8), 1581–1583. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2508.181690

- Noda, A. A., Grillová, L., Lienhard, R., Blanco, O., Rodríguez, I., & Šmajs, D. (2018). Bejel in Cuba: molecular identification of Treponema pallidum subsp. endemicum in patients diagnosed with venereal syphilis. Clinical microbiology and infection: the official publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, 24(11), 1210.e1–1210.e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2018.02.006

- Mitjà, Oriol (2017). International Encyclopedia of Public Health || Yaws, Bejel, and Pinta. , (), 476–483. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-803678-5.00500-2

- Marks, M., Solomon, A. W., & Mabey, D. C. (2014). Endemic treponemal diseases. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 108(10), 601–607. https://doi.org/10.1093/trstmh/tru128

- Mitjà, O., Šmajs, D., & Bassat, Q. (2013). Advances in the diagnosis of endemic treponematoses: yaws, bejel, and pinta. PLoS neglected tropical diseases, 7(10), e2283. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0002283

Further Reading

Last Updated: Jun 24, 2022