Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome (BHD) is a rare genetic disorder with an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance. It is a complex condition characterized by multiple benign (noncancerous) skin tumors, lung cysts, and increased susceptibility to kidney lesions. Fibrofolliculomas are a form of benign skin tumor occurring on the neck, face, and upper torso that are particular to BHD. The symptoms of the disorder usually don't show up until later in life.

Image Credit: andriano.cz/Shutterstock.com

Cause

Over the last 15 years, tremendous progress has been achieved in our understanding of the genetics and molecular mechanisms underlying the diverse symptoms of BHD. BHD is a hereditary disorder. This indicates that a family's cancer risk and other characteristics of BHD might be passed down from generation to generation.

Almost all cases of BHD are caused by a mutation in the FLCN (Folliculin) gene, which produces the protein folliculin. FLCN is regarded to be a tumor suppressor gene at the moment. A tumor suppressor gene's natural function in the body is to produce proteins that inhibit cell proliferation and hence prevent tumor formation. More research is underway to advance the understanding of the disorder.

In 2002, Nickerson and colleagues applied recombination analysis to restrict the BHD locus to a 700kb area on chromosome 17p11.2 and detected protein-truncating mutations in folliculin, a highly conserved protein, in BHD patients. Schmidt and colleagues sequenced the BHD gene directly in 30 affected families in 2005.

Using their earlier data, they were able to discover germline mutations in 84% of the families. According to the study, more than 50% of the patients had a cytosine insertion or deletion in a hypermutable polycytosine tract in exon 11, indicating that this region is a BHD mutation hotspot.

Symptoms

The clinical characteristics of BHD vary greatly in phenotypic diversity; patients can present with any combination of cutaneous, pulmonary, or renal abnormalities. Patients with pulmonary cysts and pneumothoraces but no cutaneous or renal involvement have been found to have FLCN gene mutations. BHD frequently causes pulmonary involvement, which manifests as pulmonary cysts and the formation of pneumothoraces. In more than 80% of BHD patients, multiple and bilateral lung cysts are present.

Pulmonary cysts have been seen in people of all ages, from teenagers to 85-year-olds, although they are most common in people in their fourth and fifth decades. Until a pneumothorax develops, patients with BHD are usually asymptomatic from a pulmonary aspect. Patients with BHD have a 50-fold greater risk of developing a spontaneous pneumothorax, with a median age of incidence of 38 years.

Patients with BHD are more likely to develop bilateral, multifocal renal cell carcinomas. The first case of bilateral, multifocal chromophobe renal cell carcinoma in a patient with BHD was described by Roth and colleagues in 1993. Toro and colleagues in 2008 investigated three BHD families and discovered renal cell tumors of various histologies in seven of the thirteen individuals. Following research, it was discovered that the prevalence of renal tumors in BHD patients ranges between 27 and 34 percent, with a mean age at diagnosis of around 50 years.

The majority of kidney malignancies linked to BHD are indolent, with only a few examples of metastatic dissemination recorded in the literature. Renal cysts are common in people with BHD, although it's unknown whether the prevalence is higher than in the general population.

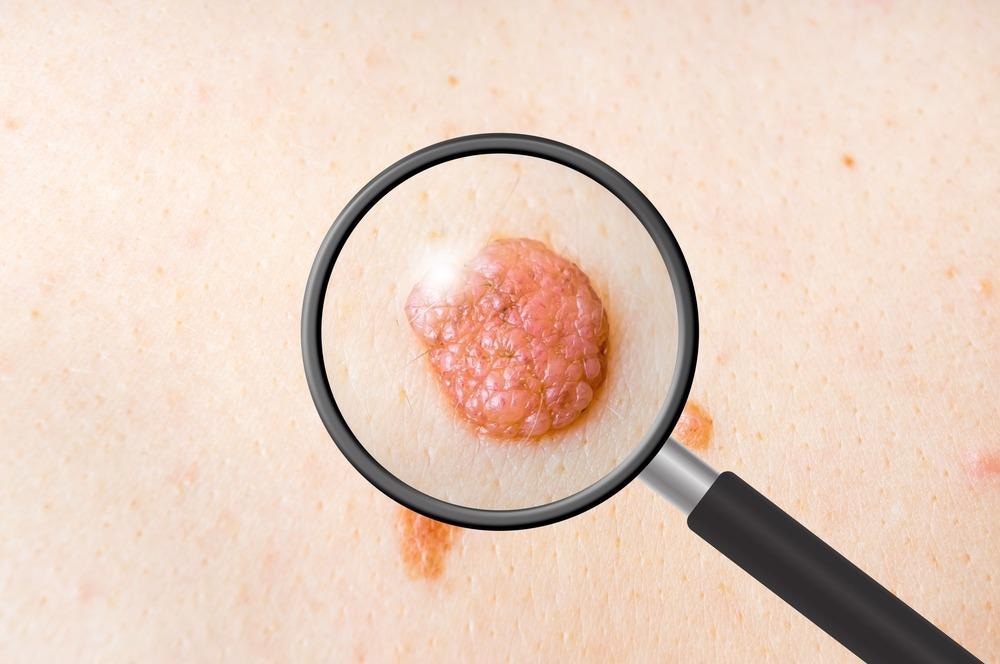

The characteristic skin findings of BHD were characterized by Birt and colleagues in 1977 as a triad of fibrofolliculomas, trichodiscomas, and acrochordons. Although, acrochordons, or skin tags, are not limited to people with BHD and are common in the general population. A morphologic spectrum has been proposed for fibrofolliculomas and trichodiscomas. Fibrofolliculomas are small, dome-shaped, whitish papules that occur after 20 years of age and are most usually seen on the face, neck, and upper body.

Through case reports and small case series, several different malignant and nonmalignant disorders have been linked to BHD. These include parathyroid adenomas, thyroid tumors, parotid oncocytomas, lung cancer, breast cancer, multiple lipomas, and so on. However, there is no evidence of a link between BHD and these conditions.

Epidemiology

BHD is a rather uncommon condition. The actual number of people with BHD and their families is unclear. The carrier frequency, on the other hand, is predicted to be 1 in every 200,000 people.

Diagnosis and Management

It can be difficult to make a diagnosis for a hereditary or uncommon condition. To begin, healthcare practitioners look at a person's medical history, symptoms, physical exam, and laboratory test findings. For individuals suspected of developing BHD, genetic testing to screen for mutations in the FLCN gene is available. Physicians should investigate BHD in patients who have a personal or family history of pneumothorax, especially if skin lesions or kidney tumors are present, to avoid misdiagnosis.

According to a recent study, doing an HRCT scan of the chest in patients who have a spontaneous pneumothorax is a cost-effective way to check for the existence of BHD. The cyst characteristics of BHD are highly distinct, and they can assist distinguish BHD from other similar disorders with great accuracy. The existence and extent of cutaneous, lung, and renal involvement should be extensively described following diagnosis.

The focus of ongoing management then shifts to kidney cancer surveillance and therapy, as well as the prevention and treatment of pneumothoraces. Destructive treatments, such as ablative laser employing an erbium-YAG or carbon dioxide laser, and electrocoagulation, are now used to treat fibrofolliculomas. The fundamental principles of pulmonary management in patients with BHD are pneumothorax prevention and therapy. Patients with BHD should be informed about their higher chance of getting a spontaneous pneumothorax, as well as the signs and symptoms that go along with it. Renal cancer is the most lethal consequence of BHD, and regular screening is critical in the long-term therapy of these patients to detect tumors early.

References:

- (2021). Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome. [Online] National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. Available at: https://rarediseases.info.nih.gov/diseases/2322/birt-hogg-dube-syndrome

- (2020). Birt-Hogg-Dubé Syndrome. [Online] Cancer.Net. available at: https://www.cancer.net/cancer-types/birt-hogg-dube-syndrome

- Gupta, N., Sunwoo, B. Y., & Kotloff, R. M. (2016). Birt-Hogg-Dubé Syndrome. Clinics in chest medicine, 37(3), 475–486. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccm.2016.04.010

- Reese E, Sluzevich J, Kluijt I, et al. Birt-Hogg-Dubé Syndrome. 2009 Sep 1 [Updated 2009 Oct 5]. In: Riegert-Johnson DL, Boardman LA, Hefferon T, et al., editors. Cancer Syndromes [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Center for Biotechnology Information (US); 2009-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK45326/

Further Reading

Last Updated: Apr 14, 2022