Chédiak-Higashi syndrome (CHS) is a rare and potentially fatal autosomal recessive disorder. A congenital immunodeficiency, CHS is characterized by frequent bacterial infections, easy bruising, oculocutaneous albinism, and recurrent pyogenic infections.

The disease is named after the French physician Moises Chediak and the Japanese physician Ototaka Higashi, however, Antonio Beguez-Cesar, a Cuban physician, was the first to report the anomalous expanded granules within leukocytes.

Mutations in CHS1, a gene encoding a putative lysosomal transport protein cause CHS. CHS affects mice and other mammals such as cats and whales, in addition to humans.

A person with oculocutaneous albinism. Image Credit: oneinchpunch/Shutterstock

A person with oculocutaneous albinism. Image Credit: oneinchpunch/Shutterstock

History

Beguez-Cesar described the first instance in 1943, a case in which three siblings presented with aberrant granules in leukocytes and neutropenia. Chediak, a Cuban hematologist, and Higashi, a Japanese physician, reported new cases in 1952 and 1954, in which they documented uneven distribution of myeloperoxidase (MPO) in neutrophil granules, which led to the condition's name.

Causes and symptoms

A mutation in the LYST or CHS1 genes is the cause of the condition. This gene controls lysosomal trafficking, as well as the production, fusion, and transit of cytoplasmic granules. It is found on chromosome 1's long arm [1q42-43]. The LYST mRNA open reading frame includes 53 exons and encodes a 3801-amino-acid protein. Human tissues with higher levels of LYST expression include the bone marrow, cerebellum, spleen, and thymus. Around 40 distinct mutations, including nonsense and missense mutations, deletions, and insertions, have been found.

Partially oculocutaneous albinism, a predisposition for bleeding, immunological dysfunction, neurodegeneration, and the likelihood of developing HLH (hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis) are all symptoms of CHS.

Hypopigmentation can be mild or severe, and it usually affects the skin, hair, and eyes. In more pigmented races, speckled hyperpigmentation or dark skin may be unusual, leading to the suspicion of other disorders and a delay in diagnosis. Dilution of pigments varies and might be slight. Pigment clusters are spread throughout the hair shaft in clumps. Pigmentation of the eyes can also vary. With iris transillumination observable on examination, iris pigment is frequently diminished. Retinal pigment may be diminished as well.

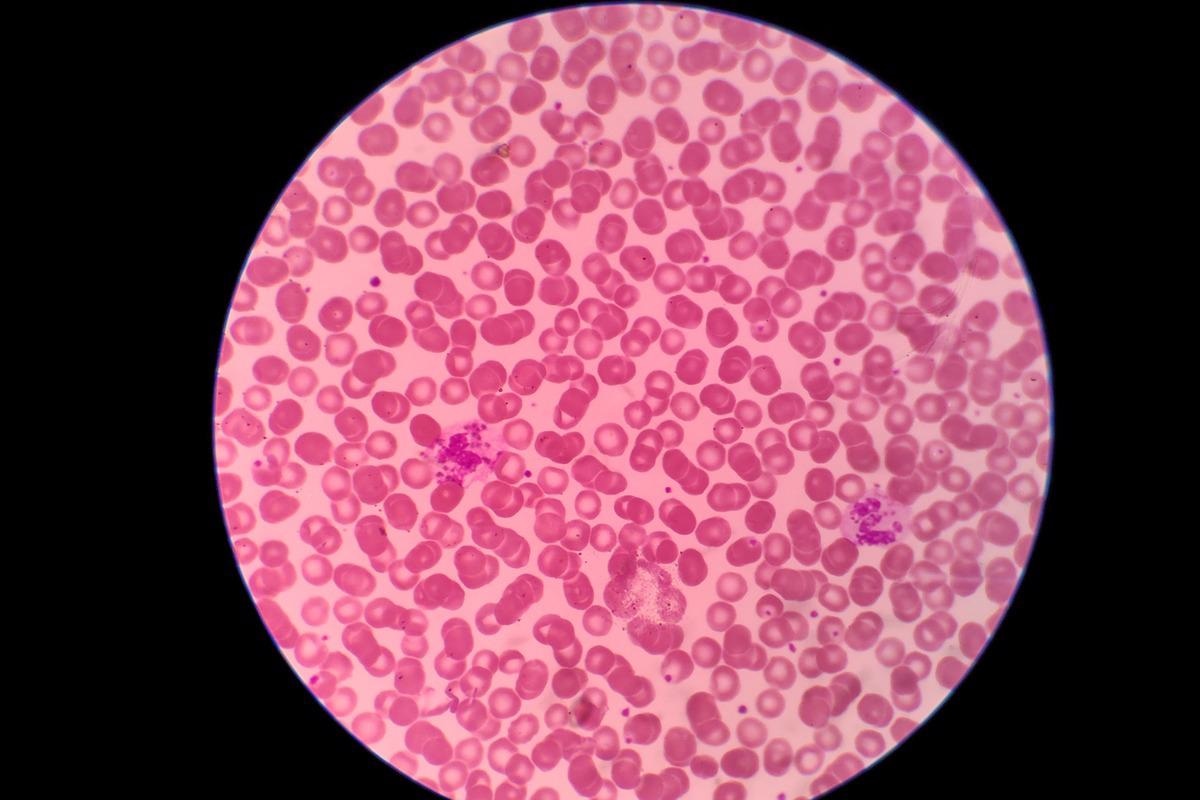

Although platelet counts are usually within acceptable limits, bleeding occurs when platelet dense granules are missing or significantly reduced. The large granules inside leukocytes that can be seen on a regular peripheral blood smear are a characteristic of CHS.

Image Credit: Phonlamai Photo/Shutterstock

Image Credit: Phonlamai Photo/Shutterstock

Patients with recurrent infections, partial oculocutaneous albinism, and coagulation abnormalities present at a young age. The severity of the disease is related to the molecular phenotype. In most cases, mutations that result in a loss of function cause the disease to manifest itself in a severe form during childhood. A missense mutation, on the other hand, is linked to a milder teenage or adult-onset illness. However, there have been two exceptions to these scenarios.

Read More: What is Albinism?

Read More: What is Albinism?

CHS can cause neurologic dysfunction and should be explored in the differential diagnosis of children and young adults who are experiencing signs of spinocerebellar degeneration or movement abnormalities for the first time. Motor and sensory neuropathies, tremors, limited cognitive abilities, learning impairments, and seizures are all common physical findings.

Patients who live into their second or third decade may develop neurologic symptoms such as parkinsonism and dementia and are frequently confined to a wheelchair.

The phases of CHS

The 'accelerated phase,' which affects roughly 85% of CHS patients within the first decade, is the most life-threatening clinical aspect of the disease. This manifestation is marked by large HLH and is known as the 'childhood' version of the disease. It commonly happens after an initial Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection, and it can look like lymphoma.

About 10 to 15 % with CHS, known as the 'adolescent' and 'adult' forms, have a less severe clinical history. During childhood, adolescence, and adulthood, these children have mostly modest hypopigmentation and a lower prevalence of infections. They have modest bleeding symptoms and live until adulthood without going through an accelerated phase. Nonetheless, they acquire increasing neurologic symptoms such as intellectual impairment, dementia, peripheral neuropathy, parkinsonism, balance problems, and tremor during adolescence or adulthood.

Epidemiology

The exact prevalence of CHS is not known. There have been fewer than 500 cases recorded in the literature around the world. Mildly affected people are also largely ignored or unreported due to phenotypic heterogeneity. There is no preference for one race over another, however, CHS is uncommon among Black people. It can impact people of all ages. However, the condition usually begins after birth and before the age of five. It is more common in children of consanguineous parents.

Only 5 cases were documented in India until 2000, but roughly 50 cases were reported in China by 2017. From 2000 to 2010, 15 patients were diagnosed with CHS in a study conducted in Japan, showing that 1 or 2 people were diagnosed per year in the country.

Diagnosis and treatment

Individuals with evidence of immunodeficiency, pigment dilution of the skin, hair, or eyes, congenital or temporary neutropenia, and symptoms of unexplained neurologic problems or neurodegeneration should be evaluated clinically.

A proband with massive inclusions within leukocytes on a peripheral blood smear and/or the discovery of biallelic pathogenic mutations in LYST on molecular genetic testing is diagnosed with CHS.

It's crucial to distinguish CHS from other hypopigmentation illnesses linked to immunodeficiencies, such as Griscelli syndrome type 2, Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome types 2 and 9, and MAPBPIP deficient syndrome. Defects in genes that encode proteins with distinct functional roles in secretory lysosomes also produce these diverse autosomal recessive disorders. Hypopigmentation, reduced primary hemostasis, decreased blood cell counts, and lymphocyte cytotoxic activity against microbial infections are all symptoms of these disorders.

Griscelli syndrome (GS) and Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome (HPS) are the two syndromes that CHS most closely resembles. Pigment decrease is present in both GS and HPS. HPS is divided into ten subgroups, each with abnormal bleeding caused by the absence of dense granules. CHS differs from GS and HPS in that it detects huge granules within leukocytes, whereas GS and HPS do not show enlarged granules on peripheral smear.

Blood tests show Chediak-Higashi Syndrome. Image Credit: Frawash/Shutterstock

Blood tests show Chediak-Higashi Syndrome. Image Credit: Frawash/Shutterstock

Allogeneic bone marrow transplant (BMT) is the treatment of choice for CHS, although it is unable to alleviate and resolve neurological abnormalities, despite being effective at addressing hematological and immunological disorders. The procedure is considered curative and must be conducted when the disease is still stable to be effective.

While waiting for BMT, treatment focuses on infections and accompanying symptoms, which are caused by a lack of neutrophil activity. Fever is treated with paracetamol, and infection is treated with amoxicillin. The huge size of the LYST coding region (about 11 kb) poses a substantial technological challenge in creating CHS gene therapy. Understanding the biological roles of LYST could lead to new CHS treatment targets.

Reference:

- Ajitkumar, A., Yarrarapu, S., & Ramphul, K. (2021). Chediak Higashi Syndrome. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Available at: https://europepmc.org/article/nbk/nbk507881#free-full-text

- de Oliveira, P. P., & Colli, V. C. (2021). Clinical aspects and main diagnostic methods of Chediak-Higashi syndrome. Clinical & Biomedical Research, 41(4).

- Sharma, P., Nicoli, E. R., Serra-Vinardell, J., Morimoto, M., Toro, C., Malicdan, M., & Introne, W. J. (2020). Chediak-Higashi syndrome: a review of the past, present, and future. Drug discovery today. Disease models, 31, 31–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ddmod.2019.10.008

- Thumbigere Math, V., Rebouças, P., Giovani, P. A., Puppin-Rontani, R. M., Casarin, R., Martins, L., ... & Kantovitz, K. R. (2018). Periodontitis in Chédiak-Higashi syndrome: An altered immunoinflammatory response. JDR Clinical & Translational Research, 3(1), 35-46.

- Lozano, M. L., Rivera, J., Sánchez-Guiu, I., & Vicente, V. (2014). Towards the targeted management of Chediak-Higashi syndrome. Orphanet journal of rare diseases, 9, 132. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-014-0132-6

- Toro, C., Nicoli, E. R., Malicdan, M. C., Adams, D. R., & Introne, W. J. (2009). Chediak-Higashi Syndrome. In M. P. Adam (Eds.) et. al., GeneReviews®. University of Washington, Seattle.

Further Reading

Last Updated: May 19, 2022