Introduction

Cause and symptoms

Molecular mechanisms in chordoma

Epidemiology

Diagnosis and treatment

Future directions

References

Further reading

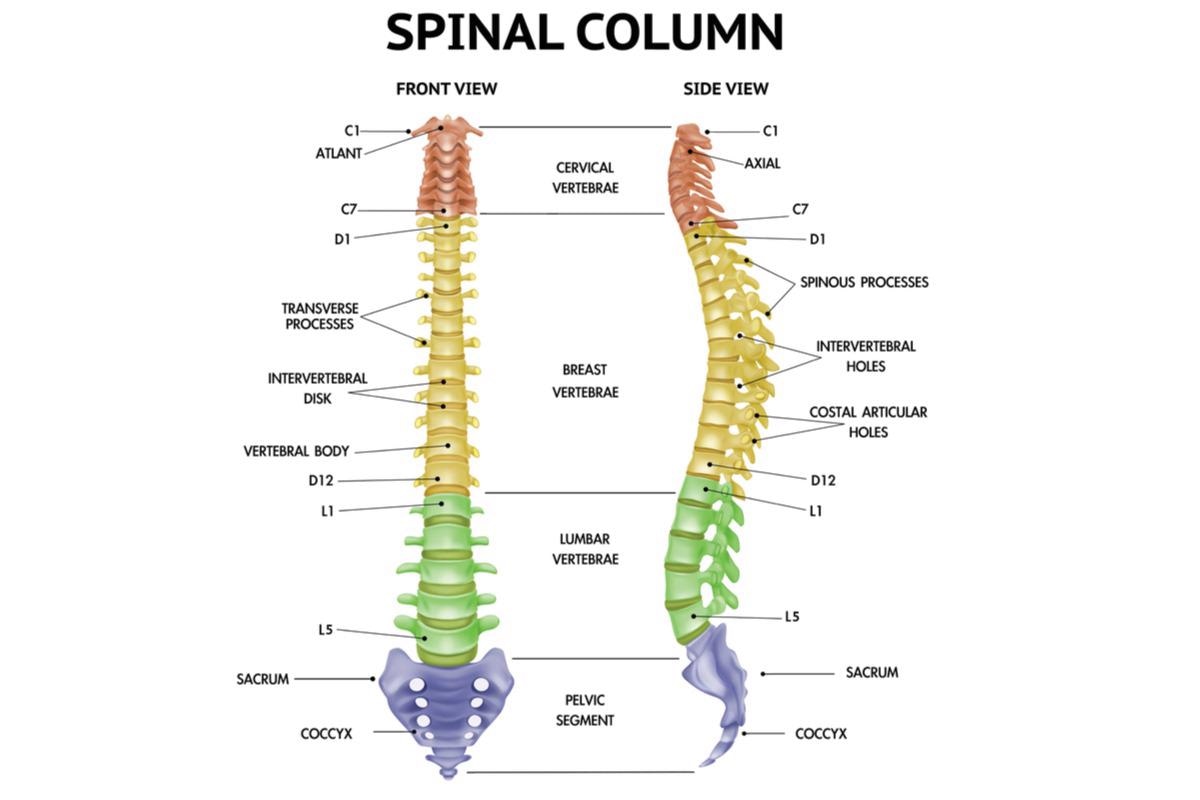

Chordoma is a rare, low-grade, malignant neoplasm originating from remnants of embryonic notochord along the spine. These tumors can appear anywhere along the spinal column, however, they are more common in the clivus and sacrococcygeal regions.

Image Credit: Vitalii Vodolazskyi/Shutterstock

Image Credit: Vitalii Vodolazskyi/Shutterstock

Virchow first identified a chordoma as a tumor of the clivus, and in 1857, he termed this tumor ecchondrosis physaliphora spheno-occipitalis, based on the notion that it is cartilage-derived.

Chordomas can be extremely recurring, aggressive, and locally invasive. They have a high tendency of metastasizing to the lungs, bones, and liver. The mainstay of treatment for these patients is surgical resection. Chemotherapy and radiotherapy are ineffective against these malignancies.

Cause and symptoms

Research is still ongoing to understand the underlying mechanism behind the development of chordoma. According to some reports, a protein called brachyury is overexpressed in chordoma. Brachyury is a transcription factor present in notochord tissues that play an important role in embryonic development. Although inherited chordomas have been recorded, they are usually sporadic, and little research has looked into their hereditary occurrence.

Chordoma is most usually diagnosed between the ages of 50 and 60, and it affects men more than women. It is uncommon in children. Primary malignancies grow along the axial spine, with one-third of cases appearing in the clivus, mobile spine, and sacrum. Chords of tumor cells and lobules with a mucoid matrix and substantial fibrous tissue in between make up the characteristic chordoma mass histologically. The appearance of the disease is determined by the tumor's location and is linked to the structures in the vicinity of the tumor's growth. Though histopathologically distinct, chondrosarcoma of the skull base possesses radiologic characteristics and a clinical appearance that is comparable to chordoma.

Most of these tumors are low to intermediate grade, but 10% of them have high-grade characteristics, such as distant metastases.

Patients with clival chordomas may experience headaches, diplopia, or other cranial nerve dysfunction, whereas patients with sacral chordomas may experience low back or buttocks pain, neuropathy, and/or gait disturbance. Due to the slow-growing nature of the disease, a non-specific symptom profile, and a reasonably vast space for tumors to occupy before generating substantially focused symptoms, patients may be diagnosed with massive tumor masses in the sacrum. Patients with sacral chordoma have lower back discomfort that is worse when they sit and is pathological. Urinary tract infections are found in up to a third of the patients.

Chordoma tumors can appear anywhere along the spinal column. Image Credit: Macrovector/Shutterstock

Chordoma tumors can appear anywhere along the spinal column. Image Credit: Macrovector/Shutterstock

Molecular mechanisms in chordoma

The molecular mechanisms that lead to chordomagenesis have yet to be thoroughly elucidated, particularly in terms of differentially expressed genes implicated in chordomagenesis. Chordoma is a cytogenetically diverse tumor with a wide range of karyotypes. It has some chromosomal abnormalities and is defined by chromosomal increases and losses across the whole genome.

Chromosomal abnormalities occur in about half of all chordomas as late events in tumor growth. Chordomas have been studied using G-banding, comparative genomic hybridization (CGH), and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) techniques to find chromosomal aberrations. Molecular cytogenetics revealed that gains of chromosomal material were most common in chordoma at 7q (42%), 20q (27%), 12q (21%), 17q (21%), and 22q (21%) while 3p (36%), 13q (24%), 4q (27%), 10q (21%), and 1p (21%) were the most frequently lost DNA sequences. In chordoma, it appeared that losses were more common than gains.

In chordomas, several indicators that contribute to tumor progression have been identified. In the majority of chordomas and chondrosarcomas, HMW-MAA, also known as CSPG4, is found. Brachyury is a T-box transcription factor that is encoded by the T or TBXT gene and has been proven to be important in notochord development. Furthermore, when compared to other neoplasms, chordoma is the only one that overexpresses brachyury. CTLA-4 is expressed in a large percentage of chordomas, according to one study. In poorly differentiated chordoma, two small investigations found that INI1 (SMARCB1) was not expressed in the nucleus.

Epidemiology

The epidemiology of chordoma is variable with an incidence of 1.7, 1, and 0.5 in 1 million in India, Japan, and Australia respectively.

In both the United States and Europe, the incidence of Chordoma is around 0.08 per 100,000, with a median age at diagnosis of around 60 years. Chordoma has a substantial age-related variability in incidence: it is extremely rare in children (1.4 and 0.8 per 10 million in the United States and Europe, respectively). It rises with the population's age and reaches a pinnacle in the eighties. In both the United States and Europe, there is a small male predominance, with a 1.5 incidence ratio between men and women.

In terms of chordoma primary site distribution, % of chordoma instances in the United States are spinal, 32% cranial, 29% sacral, and 6% have other primary sites. In Europe, 36% of primary sites are sacral, 30% are cranial, 23% are spinal, and 11% have other primary sites.

Malignant cells. Image Credit: Kateryna Kon/Shutterstock

Malignant cells. Image Credit: Kateryna Kon/Shutterstock

Diagnosis and treatment

Unfortunately, due to chordoma's slow growth and the insidious, non-specific symptoms it causes, identification might take months or even years. The median overall survival (OS) following diagnosis has been estimated to be around 6 to 7 years, however, the range of outcomes is quite large and may be connected to prognostic factors, such as therapeutic options at the time of diagnosis.

The classical (conventional) appearance of "sheets and cords of round to polygonal" tumor cells filled with occasionally large mucin-filled eosinophilic cytoplasm called physaliphorous cells confirms the diagnosis of chordoma after surgical resection or first biopsy. Staining for nuclear expression of brachyury separates chordoma from tumors with comparable morphologic characteristics in circumstances where the diagnosis is unclear.

When possible, surgery is the backbone of treatment for primary and/or recurrent chordoma, and the outcome of surgery is directly tied to the patient's projected outcome. Surgical procedures vary depending on the location of the tumor, but the goal is to obtain a local excision with clear margins in most cases. In chordoma, cytotoxic chemotherapy, which is still the gold standard for advanced soft tissue and bone sarcomas, is ineffective. Few anecdotal responses to irinotecan, anthracycline, cisplatin, and alkylating drugs have been described, mostly in dedifferentiated chordoma in the pediatric population, however, prospective evidence is scarce.

Read Next: Causes and Symptoms of Bone Cancer

Read Next: Causes and Symptoms of Bone Cancer

Future directions

In recent years, molecular characterization has improved our understanding of chordomas significantly. Despite this, the tumor's rarity, a lack of adequate in vitro and in vivo models, and the disease's heterogeneity highlight the difficulties in studying chordoma and creating effective therapeutics.

Novel mutations are being sought in recent studies to gain a better knowledge of molecular pathways and possibly uncover therapeutic targets. While there is little research on immunotherapy in chondrosarcoma, there is growing evidence and clinical trials for PD-1 (Programmed cell death protein 1) and IDH (isocitrate dehydrogenase) inhibitors.

References

- Chordoma. [Online] Omicsonline. Available at: https://www.omicsonline.org/india/chordoma-peer-reviewed-pdf-ppt-articles/ , https://www.omicsonline.org/australia/chordoma-peer-reviewed-pdf-ppt-articles/ , and https://www.omicsonline.org/japan/chordoma-peer-reviewed-pdf-ppt-articles/

- Sun, X., Hornicek, F., & Schwab, J. H. (2015). Chordoma: an update on the pathophysiology and molecular mechanisms. Current reviews in musculoskeletal medicine, 8(4), 344–352. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12178-015-9311-x

- Gulluoglu, S., Turksoy, O., Kuskucu, A., Ture, U., & Bayrak, O. F. (2016). The molecular aspects of chordoma. Neurosurgical review, 39(2), 185–196. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-015-0663-x

- Heery C. R. (2016). Chordoma: The Quest for Better Treatment Options. Oncology and therapy, 4(1), 35–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40487-016-0016-0

- Pillai, S., & Govender, S. (2018). Sacral chordoma: A review of literature. Journal of orthopaedics, 15(2), 679–684. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jor.2018.04.001

- Frezza, A. M., Botta, L., Trama, A., Dei Tos, A. P., & Stacchiotti, S. (2019). Chordoma: update on disease, epidemiology, biology and medical therapies. Current opinion in oncology, 31(2), 114–120. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCO.0000000000000502

- Traylor, J. I., Pernik, M. N., Plitt, A. R., Lim, M., & Garzon-Muvdi, T. (2021). Immunotherapy for Chordoma and Chondrosarcoma: Current Evidence. Cancers, 13(10), 2408. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13102408

Further Reading

Last Updated: Sep 5, 2024