Monkeypox represents a rare viral disease occurring predominantly in central and western Africa. The disease got its name because it was initially found in 1958 in laboratory primates. Blood screening of animals in Africa later established that other types of animals also had monkeypox, and in 1970 the first case was reported in humans.

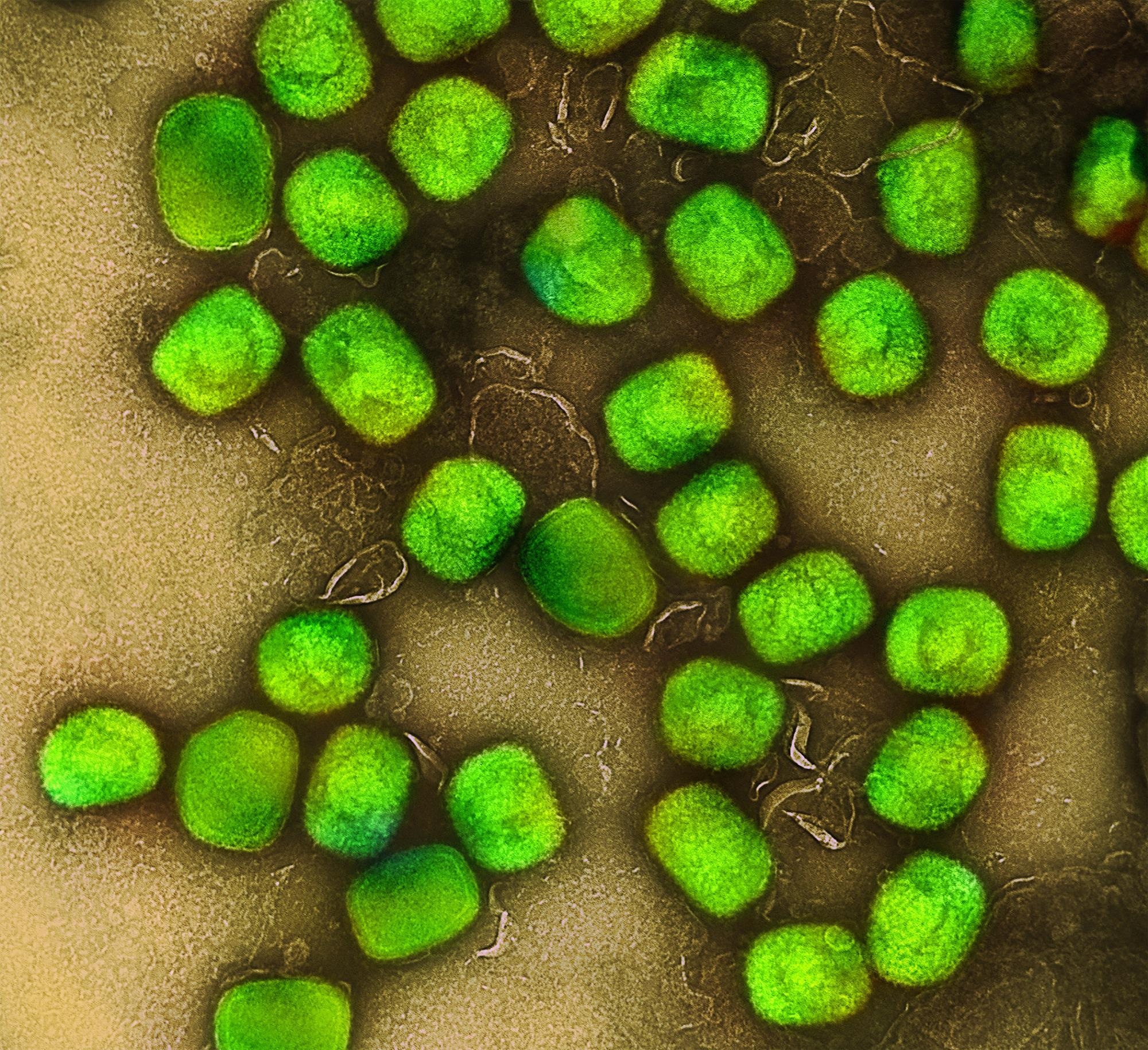

Colorized transmission electron micrograph of monkeypox virus particles (green) cultivated and purified from cell culture. Image captured at the NIAID Integrated Research Facility (IRF) in Fort Detrick, Maryland. Credit: NIAID

Colorized transmission electron micrograph of monkeypox virus particles (green) cultivated and purified from cell culture. Image captured at the NIAID Integrated Research Facility (IRF) in Fort Detrick, Maryland. Credit: NIAID

The causative agent (monkeypox virus) is a double-stranded DNA virus from the family Poxviridae and the genus Orthopoxvirus that is genetically dissimilar from other members of the genus – including variola virus, vaccinia virus, camelpox virus, cowpox virus, and ectromelia virus.

Monkey monkeypox

Two outbreaks of a nonfatal pox-like disease were initially observed in two shipments of cynomolgus monkeys arriving in Copenhagen in 1958. An orthopoxvirus was subsequently isolated on the chorioallantoic membrane, producing grayish pocks with a hemorrhagic center after three days of incubation at 35 ºC (easily distinguishable from the larger hemorrhagic pocks of cowpox virus and opaque white pocks of variola virus).

After the virus has been given recognition as a standalone species of the genus Orthopoxvirus, it was named monkey poxvirus; in addition, the Copenhagen strain is still regarded as a reference strain. After this discovery, in the next ten years, a total of nine monkeypox outbreaks were seen in captive monkey colonies throughout Europe and the US.

In most of these outbreaks, no clinical signs were typically detected until the rash appeared and developed into papules on the face, trunk, palms, and soles. The papules first become vesicular, then pustular, before scabs form 10 days after the onset of rash. The severity of clinical presentation varied among different species, with orangutans being particularly susceptible.

Human monkeypox

Human monkeypox was not regarded as a distinct entity in humans until 1970 when the virus was isolated from a child with suspected smallpox infection in The Democratic Republic of the Congo, formerly known as Zaire. The virus is most likely transmitted to humans via close contact with infected animals (usually rodents, squirrels, and primates) and the majority of the clinical characteristics mirror those of smallpox.

Clinical distinction between rash illnesses (and especially between monkeypox and smallpox) is difficult in the absence of a specific diagnostic test. Viral isolation from a clinical specimen, electron microscopy, and immunohistochemistry are valid diagnostic techniques but require advanced technical training. Thus real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is often employed to assess the presence of monkeypox virus in a lesion sample.

Although smallpox has been eradicated from the human population since 1980, there is the potential for monkeypox to fill this void. In 2003, the monkeypox virus was a cause of a cluster of cases of the disease in the US Midwest, which was the first occurrence in the Western hemisphere. 37 human cases were laboratory-confirmed during this outbreak.

In conclusion, monkeypox infection represents an important emerging disease that (based on serologic studies in Africa) could surpass original epidemiologic calculations. The introduction of a virulent monkeypox strain in a setting where individuals lack immunity to orthopoxviruses could give the virus an opportunity to exploit such a naïve population and subsequently result in an outbreak.

References

Last Updated: Jun 10, 2022