History

Causes and symptoms

Types and inheritance

Epidemiology

Diagnosis and treatment

References

Further reading

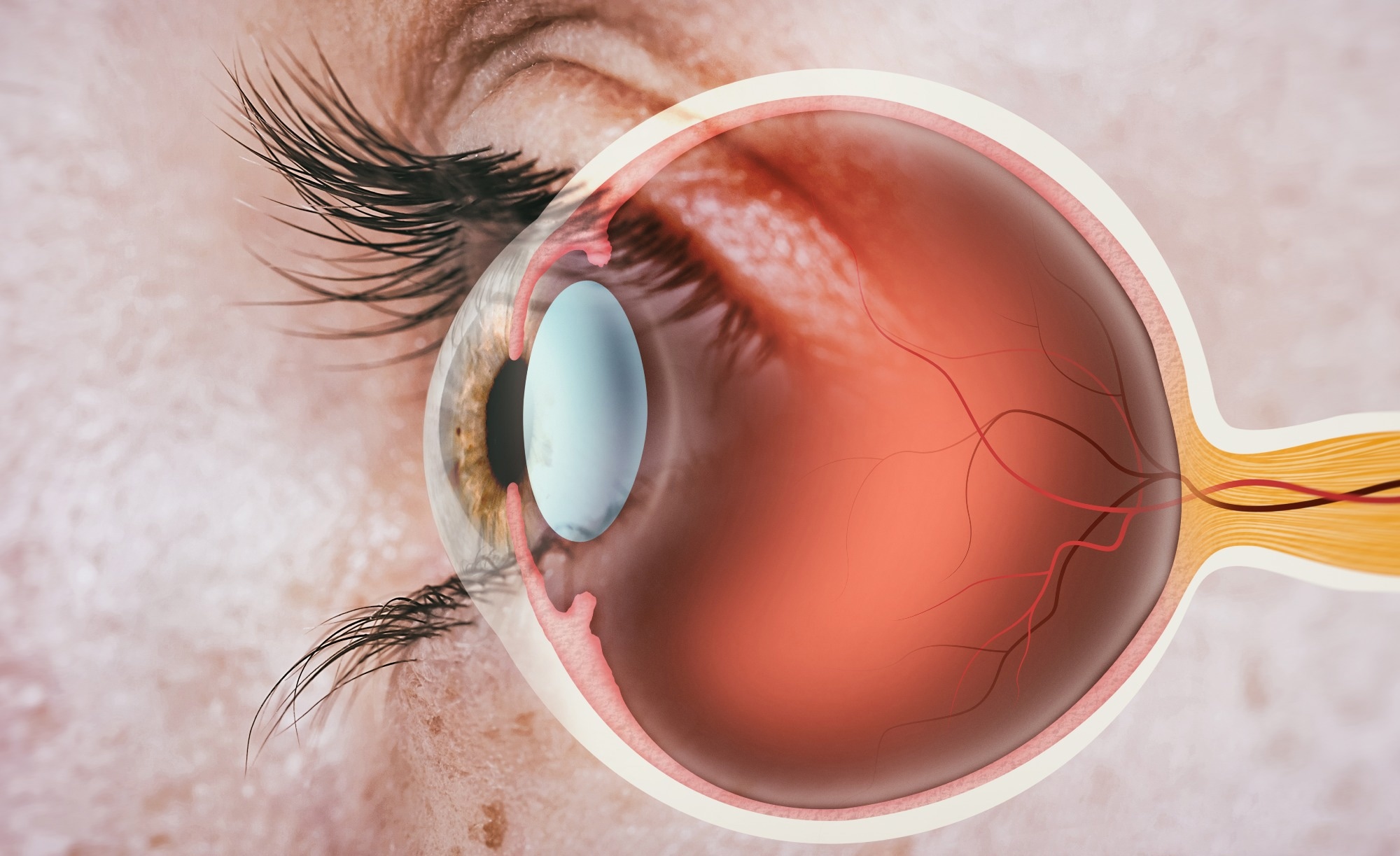

Optic Nerve Hypoplasia (ONH) is a complex congenital condition associated with moderate to severe vision loss. The optic disc is abnormally underdeveloped in this disorder with a peripapillary double-ring sign.

Optic nerve. Image Credit: SvetaZi/Shutterstock.com

Optic nerve. Image Credit: SvetaZi/Shutterstock.com

The number of retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) in ONH patients is comparatively low. The second most common underlying cause of congenital blindness, ONH, is also linked to neurodevelopmental abnormalities.

For the time being, no clinical practice guidelines or consensus standards are available for assessing and managing children with ONH.

History

In 1884, a tiny, pale optic nerve with unilaterally present retinal veins was reported in a young child. There was no apparent usable vision in that eye. This was the first presentation of a case that covered every aspect of optic nerve hypoplasia.

In a seven-month-old baby with congenital blindness, there was the first recorded link between ONH and lack of the septum pellucidum in 1941. Schwartz's report from 1915 introduced the idea of segmental ONH (also known as partial or incomplete ONH).

The author described a patient with bilateral ONH and binasal hemianopic field abnormalities. In 1972, it was proposeed that this was a congenital retrograde axonal degeneration that resulted in hemihypoplasia of the optic nerves caused by radiation injury to the optic tract or both.

Causes and symptoms

The exact etiology of ONH is unknown; however, several factors have been proposed. Young maternal age and primiparity have continuously been identified as the most important maternal factors.

Numerous studies hypothesize that the link between young maternal age and risk of unhealthy behavior and poor pre conceptional health reflects these factors. Another observation and introduction of early gestational vaginal bleeding as a potential etiologic component came from a prospective investigation including more than 200 children.

Long-standing associations with ONH and other health conditions include maternal diabetes, use of alcohol during pregnancy, and prescription or recreational medications (such as LSD, quinine, and antidepressants). Other risk factors include prenatal complications, viral infection (CMV), and maternal anemia.

ONH has been linked to several genes that are pathogenic. Four cases of probable ONH (by MRI only) with gene mutations were discovered after thoroughly assessing the genetic research literature on ONH. These include two HESX1 mutations, one OTX2 mutation, and one PROKR2 mutation. Rare genetic alterations in ONH cases have not yet been linked to a particular genotype/phenotype to explain most cases.

The most frequent presenting symptoms in children with severe bilateral ONH include loss of fixation, impaired visual behavior, roaming eye movements, nystagmus, and strabismus.

In ONH, visual impairment is the key component. Parents or physicians often observe impaired visual behavior as the initial indication of ONH. Strabismus, often esotropia, follows the development of nystagmus between the ages of one and three months. Around 80% of kids with ONH have bilateral symptoms, with 2/3 having asymmetrical symptoms.

The most frequent nonvisual cause of morbidity in children with ONH is hypothalamic dysfunction. The pituitary gland's ability to regulate temperature and behavior related to appetite and thirst are all impacted by the ensuing disruption of homeostatic systems.

Patients with bilateral ONH have a higher incidence of clinical neurologic abnormalities (65%) than patients with unilateral ONH. Patients with bilateral and unilateral ONH have been documented to have brain abnormalities. These include schizencephaly, periventricular leukomalacia, cortical heterotopias, cerebral palsy, epilepsy, and generalized encephalomalacia.

Arachnoid cysts and septo-optic dysplasia (SOD) have also been documented. Children with ONH frequently report having irregular sleep/wake cycles. According to observational studies, autism is more common in kids with ONH.

Many children with ONH experience hyperphagia with obesity or hypophagia (with or without wasting), which may be accompanied by an intolerance to particular food textures.

Types and inheritance

ONH can be separated into three clinical subgroups despite being frequently considered a more diffuse disease. These are optic nerve hypoplasia simplex (diffuse, segmental, and segmental with tilt), septo-optic dysplasia, and septo-optic-pituitary dysplasia.

Typically, ONH is assumed to be sporadic. Therefore, there is no greater danger of illness for siblings of affected children. An autosomal-recessive inheritance pattern seems to be present in most familial cases. Autosomal-dominant inheritance pattern has also been found in a few domestic situations.

Epidemiology

Since the 1980s, ONH has become significantly more prevalent. Over the past 30 years, ONH has become a more widely acknowledged cause of congenital blindness in children. In 1981, it was calculated that there were 2 cases of ONH per 100,000 people. The frequency of visual impairment increased fourfold between 1980 and 1999, according to the Swedish Register of Visually Impaired Children.

The frequency of ONH was estimated to be 1.8 per 100,000 people in British Columbia, Canada, by epidemiologic research carried out between 1944 and 1974. According to Blohme and Tornqvist's 1997 report, 7.1 out of every 100,000 Swedish children under 20 who had vision problems or were blind also had ONH.

The prevalence was found to be 10.9 per 100,000 in children under the age of 16 in the United Kingdom and 17.3 per 100,000 in children under the age of 18 in Stockholm, Sweden, according to the most recent figures.

It is unclear how common ONH is among youngsters who are visually impaired in the US. According to the 2007 US Babies Count, 9.7% of children with vision impairment had ONH as their primary cause of blindness.

Optic nerve hypoplasia

Diagnosis and treatment

A thorough guide is required to optimize care for these medically complex patients since patients with ONH exhibit a wide range of anatomical abnormalities and clinical manifestations.

There are not any proven risk indicators in place yet that physicians can use to direct care and counseling for patients with ONH and their families. Maximizing the well-being of these patients requires early detection, diagnosis, treatment, and vigilant observation employing a family-centered, multidisciplinary approach.

A timely examination must consider the age-dependent presenting characteristics of ONH and include brain imaging, hypothalamic-pituitary evaluations, and ophthalmologic tests.

Physical, occupational, and/or speech treatment is required for most patients with ONH. For ONH-related developmental impairments to be addressed, early intervention referral is essential. To help patients overcome resistance to particular food textures, therapists should focus on the early development of oral motor skills.

A neuropsychologist with experience in both autism and the evaluation of children with visual impairments should assess youngsters displaying autistic symptoms. Low doses (0.1–0.5 mg) of melatonin in the evening or soporific dosages (3-5 mg) at night can be used to treat children with disrupted sleep cycles. This might make it easier to synchronize the circadian clock.

Young children with ONH should have their vision checked at least once a year, and any refractive defects should be addressed once the child's visual acuity reaches a usable level.

Treatment for amblyopia may improve vision in the poorer eye. Children with symmetrical functional vision in both eyes and hence have some potential for binocularity require early surgical treatment of strabismus.

Although there is not a specific cure or therapy for ONH, the goal of early intervention programs and early vision stimulation programs is to lessen how much the patients' vision loss affects their overall development.

References

- Dahl S, Pettersson M, Eisfeldt J., et al. (2020). Whole genome sequencing unveils genetic heterogeneity in optic nerve hypoplasia. PloS one, 15(2), e0228622. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0228622

- Chen CA, Yin J, Lewis RA & Schaaf CP (2017). Genetic causes of optic nerve hypoplasia. Journal of medical genetics, 54(7), 441–449. doi:10.1136/jmedgenet-2017-104626

- Ryabets-Lienhard A, Stewart C, Borchert M & Geffner ME (2016). The optic nerve hypoplasia spectrum: review of the literature and clinical guidelines. Advances in pediatrics, 63(1), 127-146. doi:10.1016/j.yapd.2016.04.009

- Mohney BG, Young RC, Diehl N. (2013). Incidence and associated endocrine and neurologic abnormalities of optic nerve hypoplasia. JAMA Ophthalmol. Jul;131(7):898-902. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.65. PMID: 23640309; PMCID: PMC3710529.

- Garcia-Filion P & Borchert M (2013). Optic nerve hypoplasia syndrome: a review of the epidemiology and clinical associations. Current treatment options in neurology, 15(1), 78–89. doi:10.1007/s11940-012-0209-2

- Kaur S, Jain S, Sodhi HB, et al. (2013). Optic nerve hypoplasia. Oman J Ophthalmol. May;6(2):77-82. doi:10.4103/0974-620X.116622. PMID: 24082663; PMCID: PMC3779419.

Further Reading

Last Updated: Aug 8, 2023