Vogt−Koyanagi−Harada (VKH) disease is a vision-threatening multisystem autoimmune condition. VKH symptoms manifest in stages and usually involve ocular, auditory, neurological, and integumentary manifestations.

The actual cause of VKH disease is unknown, however, it is suspected that the symptoms are caused by an aberrant immunological response to a viral infection. It is diagnosed based on clinical symptoms and is often treated with the help of corticosteroids.

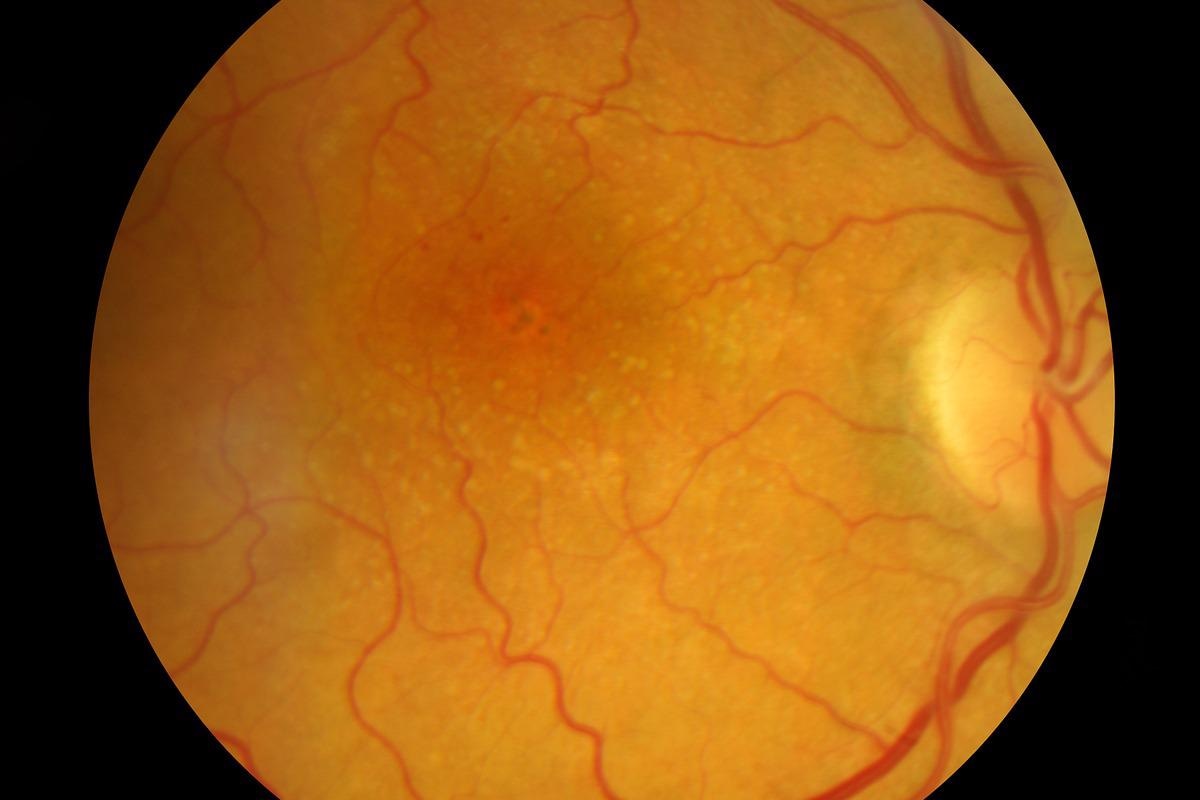

Image Credit: eye-for-photos/Shutterstock

History

In a report on the connection of nontraumatic idiopathic uveitis with poliosis, Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease was first described by Vogt in 1906. In the report, Vogt classified this ailment as a new entity of an unknown disease. Cases reported afterward, as well as Koyanagi's landmark evaluations in 1929, attracted ophthalmologists' attention to the illness.

In Koyanagi's review, sixteen instances, including 10 from literature and 6 from personal observation, were combined to form a syndrome defined by bilateral non-traumatic uveitis with poliosis, vitiligo, baldness, and dysacousia.

Most authors agreed that the cases reported by Vogt and Koyanagi were indeed one disease entity and accepted the term Vogt-Koyanagi syndrome for this ailment based on exhaustive reviews and the similarity among the instances of illness.

Causes

The actual etiology and pathogenesis of VKH disease have yet to be determined. However, tremendous progress has been made in recent decades due to significant advances in numerous domains of fundamental science.

Viruses found in patients with VKH disease support the theory that the disease is triggered by a microbial infection. In the prodromal stage, meningeal symptoms such as fever, headache, and meningismus have led to the theory that VKH disease is caused by a viral infection.

VKH appears to be an autoimmune inflammatory disorder caused by CD4+ T lymphocytes that target melanocytes, according to immunological and histological studies. In people who have a reduced tolerance to melanocytes due to a lack of T regulatory cells, these activated T cells are likely to start the inflammatory process by producing cytokines including IL 17 and IL 23.

The exact cause of the altered tolerance to melanocytes is unknown. The combination of genetic vulnerability and viral infection in those who express HLA DRB1*0405 may play a role in starting the autoimmune process.

Symptoms and phases

VKH has four distinct clinical phases: prodromal, uveitic, convalescent, and recurring. Headache, meningismus, hearing loss, poliosis, and vitiligo are some of the extra-ocular signs that might occur. The prodromal phase may be characterized by a viral infection and can persist anywhere from a few days to many weeks. Clinical symptoms are largely extra-ocular in this phase, before ocular involvement, and include headache, meningismus, and fever. During this time, one or more symptoms may appear.

Acute uveitis, usually bilateral posterior uveitis, marks the start of the acute stage. This stage normally lasts a couple of weeks. Within the first two weeks, the most common finding is either choroiditis or non-granulomatous chorioretinitis. Depigmentation of the choroid, vitiligo, and poliosis occur several weeks to months after the acute uveitic phase. This recuperative period usually lasts for several months.

A mild panuveitis with recurrent episodes of anterior uveitis characterizes the chronic recurrent stage. This chronic recurrent phase usually appears six to nine months after the first appearance. RPE proliferation, subretinal neovascular membranes, subretinal fibrosis, posterior synechiae, posterior subcapsular cataract, and open-angle glaucoma are common symptoms observed during this phase.

Image Credit: sruilk/Shutterstock

Epidemiology

VKH is more frequent in Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East than in other parts of the world. VKH is rare in the United States, accounting for only 3-4 percent of tertiary care referrals. Asian, Hispanic, Native American, and Asian Indian populations are more likely to be impacted, and white and black individuals from Sub-Saharan Africa are less likely to be affected.

Although women are more impacted by VKH overall, a higher proportion of men in the Japanese population may be affected. VKH is more common in adults than in children. People in their second to fifth decades of life are primarily affected by VKH, though there have been reports of children as young as three years old and geriatric patients as old as 89 years old being affected by this condition.

Diagnosis and treatment

The symptoms, clinical exams, eye exams, and imaging studies are taken into consideration while diagnosing Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease. Before VKH disease can be identified, other more prevalent disorders may need to be ruled out. To aid in the diagnosis of VKH disease, a collection of typical signs and symptoms has been established.

Examination findings can greatly vary depending on the clinical stage of the disease and the ethnicity of the patient, which may be a confusing factor in the diagnosis of the disease. In the eyes of VKH, the use of ever-evolving imaging technology has enabled better visibility and knowledge of the underlying disease process.

One of the oldest and most extensively used imaging techniques for this condition is fluorescein angiography. B-scan ultrasonography is a noninvasive auxiliary test that can also be used to diagnose VKH disease in its early stages. The visual, neurologic/auditory, and integumentary systems must all be involved to diagnose total disease.

The most common treatment for VKH is corticosteroids in the acute phase of the disease, with immunomodulatory therapy added as needed. Corticosteroids, both oral and intravenous, have been used successfully. Oral corticosteroids have been linked to a lower risk of severe vision loss when used to treat VKH. To avoid development into the chronic stage of the disease and to prevent future recurrences, gradually tapered systemic corticosteroids should be maintained for several months.

Immunosuppressive drugs (such as cyclosporine, azathioprine, and methotrexate) are used to suppress ocular inflammation in individuals who are in the chronic phase or have chronic recurrent disease. They can also be given to patients that are intolerant or resistant to corticosteroids.

New tools for evaluating the microbiome composition in VKH patients may reveal if the microbial flora plays a role in the disease's onset or recurrence. It could also help researchers figure out how the microbiome interacts with predisposing genetic variables and if it has an impact on autoimmunity and inflammation, as well as whether this knowledge can be used to treat the condition.

Research into the causes and triggers of immunological dysregulation in this disease could lead to the discovery of new treatment targets.

Read now: What is a Rare Disease?

Read now: What is a Rare Disease?

References:

- O'Keefe, G. A., & Rao, N. A. (2017). Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease. Survey of ophthalmology, 62(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.survophthal.2016.05.002

- Du, L., Kijlstra, A., & Yang, P. (2016). Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease: Novel insights into pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment. Progress in retinal and eye research, 52, 84–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.preteyeres.2016.02.002

- Burkholder B. M. (2015). Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease. Current opinion in ophthalmology, 26(6), 506–511. https://doi.org/10.1097/ICU.0000000000000206

- Sakata, V. M., da Silva, F. T., Hirata, C. E., de Carvalho, J. F., & Yamamoto, J. H. (2014). Diagnosis and classification of Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease. Autoimmunity reviews, 13(4-5), 550–555. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2014.01.023

- Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease. [Online] NIH-GARD. Available at: https://rarediseases.info.nih.gov/diseases/7862/vogt-koyanagi-harada-disease

Further Reading

Last Updated: May 19, 2022