A rare inherited disorder, Xeroderma Pigmentosum (XP) is a photosensitive condition characterized by high susceptibility to skin cancers. XP follows the autosomal recessive pattern of inheritance. Photosensitivity (with easy skin blistering after modest sun exposure), early freckling, and the development of lentiginous pigmentation are all symptoms of poor UV-radiation-induced damage healing.

A sunburn response that is excessive and extended is seen in about 60% of those who are affected. Neurological disorders of various severity might occur in a minority of instances.

XP has been discovered on every continent and in people of all ethnicities.

Image Credit: Xeroderma Pigmentosum/Shutterstock

History

Dermatologist Moriz Kaposi originally reported XP in 1874 after observing wrinkling, checkered pigmentation, tiny dilatations of the arteries, skin contraction, and the development of skin-based malignancies in four individuals with thin, dry skin.

Following reports, the disease's spectrum was enlarged to encompass neurologic problems, as well as a severe variant with dwarfism, gonadal hypoplasia, and learning disabilities, in addition to the classic symptoms of XP.

The disease pathogenesis was identified as congenital excessive sensitization of the skin to ultraviolet radiation of the sun as early as 1926, with clear value in sun exposure prevention methods.

Cause and genetic mechanism

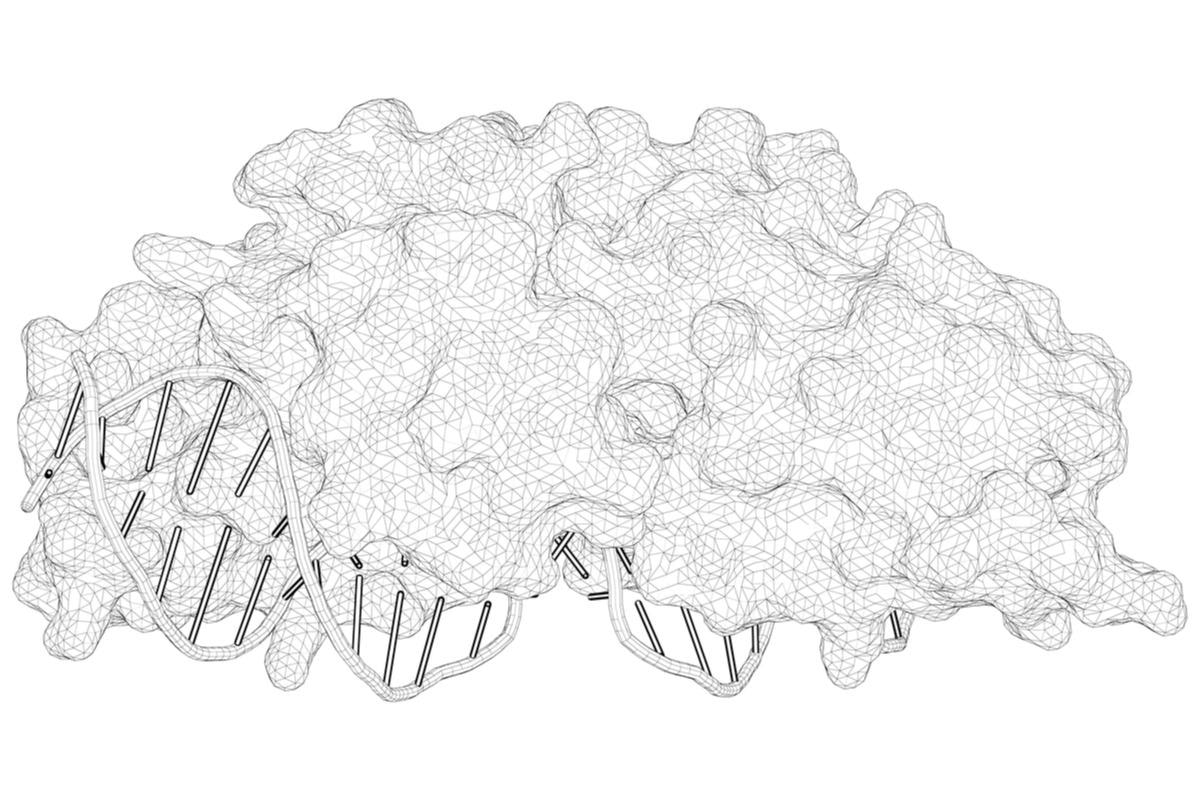

Mutations in eight genes can result in the development of XP. These are genes involved in DNA repair, namely, XPA, XPB (ERCC3), XPC, XPD (ERCC2), XPE (DDB2), XPF (ERCC4), XPG (ERCC5), and XPV (POLH).

UV radiation from the sun, as well as hazardous compounds contained in cigarette smoke, can cause DNA damage. DNA damage is normally repaired by normal cells before it causes complications. DNA damage is not repaired regularly in persons with XP. Cells malfunction as more anomalies in DNA develop, eventually becoming malignant or dying.

Many of the xeroderma pigmentosum genes are involved in a DNA-repair mechanism called nucleotide excision repair (NER). In this process, the proteins produced by these genes have a variety of activities. They detect DNA damage, unwind damaged segments of DNA, snip off (excise) the abnormal parts, and replace the damaged areas with the right DNA. Cells with inherited defects in the NER-related genes are unable to complete one or more of these processes.

The main symptoms of xeroderma pigmentosum are caused by an accumulation of unrepaired DNA damage. UV radiation can disrupt genes that control cell development and division, causing cells to die or grow too quickly and uncontrollably. Cancerous tumors can arise as a result of uncontrolled cell expansion. Although the brain is not exposed to UV rays, it is assumed that an accumulation of DNA damage causes neurological disorders. Other variables, according to researchers, may cause DNA damage in nerve cells. Why some persons with XP develop neurological problems while others do not is unknown.

Symptoms

Patients with XP frequently exhibit unique clinical manifestations such as increased sensitivity to UV exposure (resulting in painful sunburns), skin dryness (also known as xerosis), and developing freckle-like pigmentary abnormalities. They also have varying degrees of skin damage, early photoaging, and a higher prevalence of malignant tumors in the face, head, and neck. Furthermore, some patients have neurologic and ophthalmologic deterioration with time.

Extreme sensitivity to sunlight is the first symptom in around 60% of patients, and it can take days or weeks to resolve. The remaining 40% of instances do not show any signs of sunburn. Telangiectasia is a late symptom. There may be stucco keratoses, which are easily distinguished from sun keratoses. Because all skin changes are caused by UV exposure, the severity of these changes is determined by the amount of sun exposure, the Fitzpatrick skin type, and the degree of skin protection from the sun. Individually, the consequences can be quite different.

25% of patients with XP experience neurological symptoms although the severity and timing of their onset might vary substantially. Attenuated or absent tendon reflexes, speech and gait difficulties, gradual hearing loss, and cognitive decline are some commonly observed symptoms.

Skin cancer (34%) is the leading cause of death in XP patients, followed by neurological degeneration (31%), and internal cancer (17%), which includes brain cancer (astrocytoma, sarcoma, medulloblastoma) and leukemia (acute lymphatic leukemia, myelogenous leukemia), among others.

Image Credit: Evgeniy Kalinovskiy/Shutterstock

Types of XP

XP is classified into the following types: XPA, XPB, XPC, XPD, XPE, XPF, XPG, and XPV. After modest sun exposure, the XPC, XPE, and XPV kinds have been linked to less severe sunburn, and they may tan but still develop aberrant pigmentation. Neurodegeneration isn't observed in all types equally, although it's most common in the XPA, XPB, XPD, XPF, and XPG types, while it's rare in the XPC and XPE types.

In the United States, Europe, and North Africa, the most common complement type is XPC, while in Japan, the most common complement type is XPA.

Epidemiology

XP has been discovered on every continent and in all racial groups. Males and females are both affected, which is consistent with autosomal recessive inheritance. Affected patients can be found all over the world, with estimates ranging from one in every million in the United States to one in every 22,000 in Japan. The Middle East and North Africa have also been identified as regions with a significant number of cases.

XP patients have a 10,000-fold increased risk of non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC), such as basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), compared to the general population, while melanoma is reported to be 2000-fold more common in XP.

Diagnosis and treatment

Although cases with later onset and limited signs have been recorded more lately in the literature, clinical suspicion for XP should be raised in individuals who demonstrate early cutaneous manifestations of sun damage. Robust cellular assays for faulty DNA repair, which are available in numerous countries, can be used to confirm the diagnosis firmly. The detection of unscheduled DNA synthesis in cultured skin fibroblasts is the most often utilized test. Additional genetic testing can be used to determine the gene that is defective in XP patients.

To date, XP patients are managed according to worldwide recommendations, which include early genetic/clinical diagnosis and long-term UV protection. Reduced sun exposure can be achieved by using total sunscreen lotions daily, or by wearing gloves, hats, sunglasses, and UV-blocking glasses on automobile windows, as well as avoiding exposure during the day.

Some anti-cancer medications have been investigated as an alternative to surgical removal of skin tumors for the treatment of XP patients. The topical use of 5-Fluorouracil (5-FU) or Imiquimod has proven to be the most effective medicine among these.

Because there are no cures for XP, patients' cancer-free longevity is dependent on persistent full-body protection and frequent surgical removal of skin malignancies.

Xeroderma pigmentosum is a field that is always changing. The attention is shifting away from the complexities of nucleotide excision repair and toward fixing the downstream metabolic impairments that occur from the NER malfunction, which could lead to new therapeutic approaches.

References:

- Piccione, M., Belloni Fortina, A., Ferri, G., Andolina, G., Beretta, L., Cividini, A., De Marni, E., Caroppo, F., Citernesi, U., & Di Liddo, R. (2021). Xeroderma Pigmentosum: General Aspects and Management. Journal of personalized medicine, 11(11), 1146. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm11111146

- Weon, J. L., & Glass, D. A., 2nd (2019). Novel therapeutic approaches to xeroderma pigmentosum. The British journal of dermatology, 181(2), 249–255. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.17253

- Lehmann, J., Seebode, C., Martens, M. C., & Emmert, S. (2018). Xeroderma Pigmentosum - Facts and Perspectives. Anticancer research, 38(2), 1159–1164. https://doi.org/10.21873/anticanres.12335

- Moriwaki, S., Kanda, F., Hayashi, M., Yamashita, D., Sakai, Y., Nishigori, C., & Xeroderma pigmentosum clinical practice guidelines revision committee (2017). Xeroderma pigmentosum clinical practice guidelines. The Journal of dermatology, 44(10), 1087–1096. https://doi.org/10.1111/1346-8138.13907

- Black J. O. (2016). Xeroderma Pigmentosum. Head and neck pathology, 10(2), 139–144. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12105-016-0707-8

- Black J. O. (2016). Xeroderma Pigmentosum. Head and neck pathology, 10(2), 139–144. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12105-016-0707-8

- Lehmann, A. R., McGibbon, D., & Stefanini, M. (2011). Xeroderma pigmentosum. Orphanet journal of rare diseases, 6, 70. https://doi.org/10.1186/1750-1172-6-70

Further Reading

Last Updated: May 19, 2022