Introduction

Normal physiology of the heart

Pathology and need for a pacemaker

Modern Pacemakers

References

Further reading

Introduction

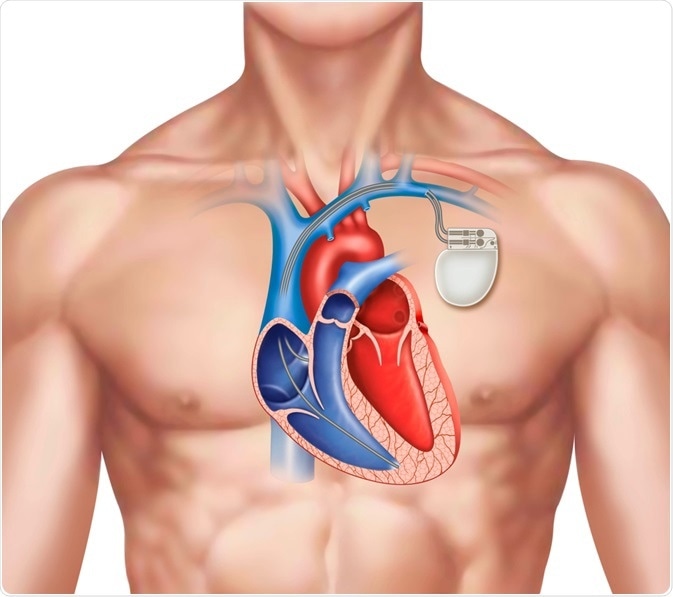

A pacemaker is a small battery-operated electronic device placed in your body, usually by surgery, to help stabilize and regulate abnormal heart rhythms to a more regular pattern. A temporary pacemaker helps a recovering heart to manage a slow heartbeat (bradycardia) after a heart attack. In these cases, the pacemaker may be attached to the clothes rather than implanted under the skin. Permanent pacemakers are implanted in patients with chronic heart failure or a slow or irregular heartbeat.

Image Credit: ilusmedical / Shutterstock.com

Normal physiology of the heart

The heart has its own pacemaker (an electrical system) called the sinoatrial (SA) node, which lies at the top of the organ. The SA node generates a regular electrical impulse that travels across the heart muscles via nerves causing the muscles to contract and relax to form a heartbeat, usually 60 to 100 beats a minute for adults at rest. Other components of a hearts' conduction and excitation system are intermodal tracks, Bachmann's bundle, the atrioventricular (A-V) node, the bundle of His, bundle branches, and Purkinje fibers. This pumping of the heart maintains blood circulation throughout the body.

Pathology and need for a pacemaker

When the inbuilt pacemaker of the heart does not function adequately by itself, the circulation of blood is severely compromised. Aging, medications, damage to heart muscles from a heart attack and specific genetic conditions can cause an irregular heart rhythm, including cardiac arrhythmias that upset its coordination, resulting in reduced hemodynamic (pumping) performance of the organ. Therefore, an artificial pacemaker is implanted to help the heart beat regularly. Although rare, allergic reactions, blood clots, and lead malfunction are some possible side effects of pacemaker procedures.

The pacemaker is implanted underneath the chest skin just below the collar bone and connected to the heart with tiny wires. The whole procedure takes around an hour to complete.

The two main components of a pacemaker include a pulse generator and connecting leads (electrodes). The former is a small metal container housing a battery and the electrical circuitry that controls the rate of electrical pulses sent to the heart. The computerized electrical circuit converts any generated energy into electrical impulses that travel via the wires to the heart.

The electrodes, one to three in number, are placed in one or more chambers of the heart to deliver the electrical pulses to adjust the heart rate. Modern leadless pacemakers, however, are implanted directly into the heart muscle. Chest radiography helps doctors identify the pacemaker and the lead type, the lead course within the heart, and the type of lead fixation to the myocardium. The pacemaker leads have a lifespan of approximately eight to 10 years.

In modern batteries, a layer of semisolid lithium iodide separates the anode and the cathode. Pacemakers with no telemetry indicate that the battery voltage is getting low, typically between two and 2.4V, called an elective replacement indicator (ERI). ERI could include changes to the pacing mode or pulse duration. If the battery voltage is allowed to drop as low as 1.8V, the pacemaker electronics become erratic and require immediate change.

The problem of electrode-lead fracture continued to plague embedded pacemakers for years. These leads flexed about 30 to 106 times a year and often failed from fatigue. In 1959, Elema Schonander developed a new cable that consisted of four thin bands of stainless steel wound around a core of the polyester braid and insulated with soft polyethylene. It survived over 184 million flex cycles to last at least six years. Additionally, because pulse generator pockets are extravascular, they are prone to infection, with the lead serving as a conduit for infection to the vascular system. Finally, since the leads cross the tricuspid valve in the heart, they cause backflow and mechanical damage in the longer term. The most apparent solution is a single component leadless pacemaker, or a multicomponent leadless system, where a tiny seed is placed within the left ventricle to act as an energy transducer. Another option could be a more accessible, large component system, which feeds nearby ultrasonic or electromagnetic energy to the seed, which, in turn, is converted to a pacing pulse.

In 1959, Dr. Seymour Furman, a cardiac surgeon, first inserted a pacemaker lead through the basilic vein and secured the electrode to the endocardium. By the early 1960s, all internal pacemakers began to use this procedure. Combining the advancement of implantable pacemakers with the transvenous access technique reduced skin burns and infections and avoided major surgery. This technique remains the gold standard for most patients who require pacemakers, though some pediatric patients with complex congenital cardiac abnormalities still need thoracotomies.

Modern Pacemakers

For the past 50 years, the basic construction of pacemakers has remained the same, with all using an implanted extravascular pulse generator connected to a lead. Furthermore, the demand concept, invented in 1964 by Berkovitz, is the basis of all modern pacemakers. It uses the same set of electrodes to monitor cardiac activity and stimulate it.

Pacemaker. Image Credit: Birgit Reitz-Hofmann / Shutterstock

Pacemaker. Image Credit: Birgit Reitz-Hofmann / Shutterstock

All modern pacemakers use complementary metal oxide semiconductor (CMOS) technology. CMOS technology uses only some random-access memory (RAM) to store diagnostics and history and a few kilobytes of read-only memory (ROM) containing the program. All the components are housed within a titanium case with a connector block to attach the leads. The outer casing is generally laser etched with manufacturing and model details. Some models also include radio-opaque symbols of a characteristic shape so that an X-ray image identifies the device.

Regarding pacemaker evolution, motion harvesting pacemakers are being tested in animal models and should become available for human trials shortly. They use cardiac and pulmonary motion throughout a patient's life to provide a reliable source of energy for scavenging. Furthermore, they use piezoelectric nanowires attached to a flexible substrate, generating up to 100 nano ampere current and voltages of up to two volts sufficient to power the pacemaker microelectronics.

What is a pacemaker?

References

Further Reading

Last Updated: Sep 6, 2022