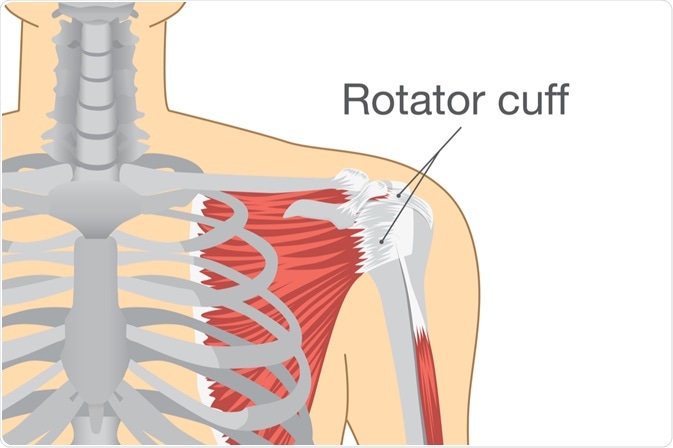

The shoulder represents one of the most elaborate areas of the human body consisting of a ball and socket joint, which offers an extreme range of motion, but it is also commonly prone to dysfunction. The rotator cuff, which is also known as the rotor cuff, is the group of muscles and their tendons that are responsible for stabilizing the shoulder.

Image Credit: solar22 / Shutterstock.com

Electromyography and other techniques have been used to study normal and abnormal shoulder motion. Adequate knowledge about muscle roles and the proper functioning of rotator cuff is pivotal in order to provide potential guidelines for interventions aimed at improving shoulder motion and function in certain pathologies.

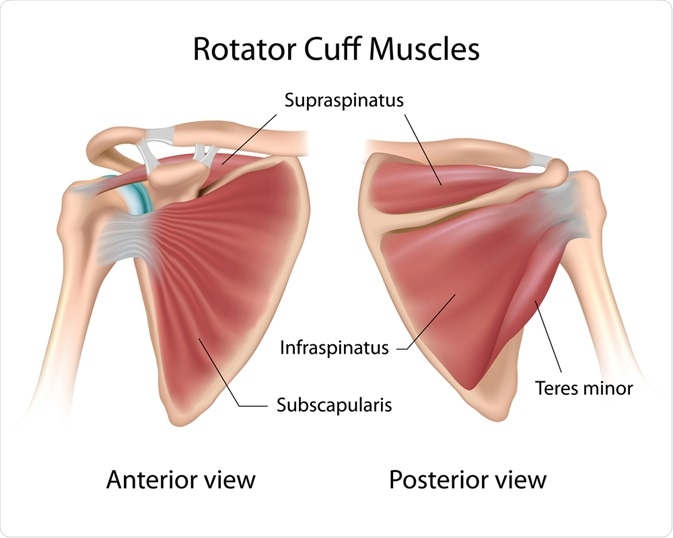

Anatomical review

A normal anatomy of the rotator cuff consists of four muscle-tendon units including the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis. Each of these muscles originates on the body of the scapula (shoulder blade), enveloping the humeral head as they insert on to their respective protuberances on the proximal humerus, which is the upper part of the long bone in the arm.

The rotator cuff adheres to the glenohumeral capsule, except at the rotator interval and axillary recess, in order to provide circumferential reinforcement. The insertion pattern of the rotator cuff tendons is consistent across individuals, and the tendons are arranged in a horseshoe-shaped configuration around the humeral head.

Image Credit: Alila Medical Media / Shutterstock.com

Supraspinatus muscle is not only an initiator of lateral abduction (a movement away from the midline), but acts throughout the range of abduction of the shoulder. Its power of abduction movement is equal to the deltoid muscle. The infraspinatus allows for external rotation and posterior abduction of the upper extremity.

Along with the infraspinatus muscle, the teres minor assists in external rotation of the shoulder. The main internal rotator of the shoulder is the subscapularis muscle, which is the strongest and largest muscle of the rotator cuff, providing 53% of its total strength.

Multiple vessels contribute to the vascularity of this structure. Superior, anterior and posterior portions are supplied by the anterior and posterior humeral circumflex vessels, while other contributions are made by the suprahumeral branches of the axillary artery, branches of the subscapular artery, and, in most individuals, a branch of the thoracoacromial artery.

The rotator cuff is a group of four muscles and their tendons that wrap around the front, back, and top of the shoulder joint. These let the shoulder function through a wide range of motions. Stress on the shoulder may cause them to tear, which can make routine activities difficult and painful.

Functions of the rotator cuff

The four muscles of the rotator cuff have three main functions that include rotating the humerus, compressing the humeral head into the glenoid cavity, which is the concavity in the head of the scapula that receives the head of the humerus, as well as providing muscular balance to other musculature of the shoulder. Compression of the humeral head into the glenoid cavity aids significantly in the dynamic stability of the shoulder.

The rotator cuff is critical to the stabilization and prevention of excess superior translation of the humeral head, as well as production of glenohumeral external rotation during arm elevation. This structure undoubtedly plays a pivotal role in the balanced and coordinated movement of the humerus, but also in maintaining glenohumeral joint (shoulder joint) stability.

During normal physical activity, the force that the rotator cuff transmits falls between 140 and 200 newtons. The rotator cuff stabilizes the glenohumeral joint via force couples in both the coronal and transverse planes. The biomechanical relationship between rotator cuff muscles and the mechanism of force couples provides a better understanding of how and why failure occurs in the rotator cuff.

References

Further Reading

Last Updated: Feb 17, 2023