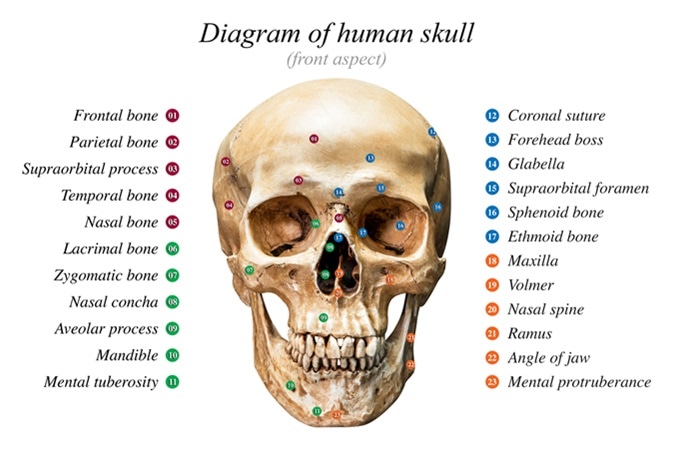

Following fractures of the nasal bone, zygomatic fractures are the second most common fractures of the face and predominantly occur in males during their twenties and thirties. The zygomatic bone, in particular the malar eminence, plays an important part in the appearance of our faces. It is a component of the lateral wall and floor of the orbit, as well as the zygomatic arch. Moreover, it contains tiny holes, also known as foramina, which allow for the passage of important neurovascular structures.

The zygomaticotemporal and zygomaticofacial arteries, as well as nerves, pass through the foramina found in the zygomatic bone. These supply sensory innervation to the anterior part of the temple and the cheeks. The zygomatic arch serves as an important bone for the attachments of structures such as the fascia of the temporalis and the origin of the masseter muscle. Also located on the zygomatic bone is the Whitnall tubercle, which is the point of attachment for the tendons of the lateral canthi of the eyelids and is essential for maintaining the contour of the lids.

Image Credit: Fotoslaz / Shutterstock

Etiopathogenesis

In order for a fracture to occur in the zygomatic bone, kinetic force is required. The severity of the injury is directly proportional to force of the impact. The zygomatic bone is quite sturdy as it serves as a buttress between the skull and the maxilla. However, its prominence makes it particularly vulnerable to injury, especially when impact occurs on either side of the face. The most common cause of zygomatic fractures is violent altercation. This is then followed by motor vehicle accident (MVA). These fractures can also occur during falls or activities such as cycling or skiing.

Fractures in the zygomatic bone can extend through suture lines, namely, the zygomaticofrontal, zygomaticotemporal and zygomaticomaxillary. Furthermore, the lines of the fracture can also extend through the articulation that the zygomatic bone has with the sphenoid bone’s greater wing. Force that is mild to moderate may result in fractures that are non-displaced. This means that there may be a crack in the bone, but its alignment is not disturbed. In contrast, forces from higher energy impacts may cause displacement, while considerably higher forces, for example from a MVA may result in comminuted fractures. This is the splintering of the bone into multiple fragments.

Clinical Presentation

A patient with a zygomatic fracture can present with a wide range of signs and symptoms depending on the kinetic force that caused the resultant damage. There will certainly be pain and limitations with regards to movements that are associated with the zygomatic bone. If there is associated injury to the orbit and ocular structures, then there might be localized hemorrhaging as well as double vision. Patients may develop trismus (i.e. the inability to fully open the mouth) and have difficulty with chewing. There may also be bleeding through the nose, which depends on the severity of the injury.

The cheekbone of these patients may be flattened due to the malar eminence being depressed. There is a palpable ‘step defect’ along the infraorbital rim, lateral orbital region or the zygomaticomaxillary buttress. Furthermore, there is what may be referred to as the ‘flame sign’ that arises as a result of the tendon of the lateral canthal being depressed and disrupted. Patients may also report parasthesia in the areas that are supplied by the nerves that are affected by the injury.

Classification

Several different classification systems have been used to describe zygomatic fractures to assist with their management. The well-known Knight and North classification system from 1961 is based on 6 distinct groups of zygomatic fractures. Fractures without significant displacement of the zygomatic bone are considered as group I fractures. Those with isolated displacement are classified as group II, whereas fractures that are un-rotated (i.e. have displaced bodies) are group III fractures. Group IV and V fractures are those that are medially and laterally rotated, respectively. If there is an additional fractured line within the main fragment, then these are categorized as group VI fractures.

A more modern classification system, known as the Manson classification system, uses CT scans in the assessment of zygomatic fractures. The Manson classification systems groups zygomatic fractures into three general categories – low, middle and high-energy zygomatic fractures. Low-energy fractures are those that do not result in displacement of the bone. Middle-energy fractures are those that can moderate displacement and, in some cases, comminution. High-energy fractures are those with severe displacement and comminution.

Other classification systems include the Henderson, Ellis, Zing, Larson and Thompson, and Rowe and Killey classifications. None of the systems are accepted universally and most of them are based on the site of the fracture as well as its degree of comminution and displacement, whether inferior, medical or posterior.

Management

The advanced trauma life support (ATLS) protocol is followed in patients who were involved in traumatic accidents. This protocol assesses the airway, breathing and circulation, while taking the necessary steps to ensure that they are adequately maintained. The Glasgow coma scale is used to assess the patient’s mental status and a neurological examination where applicable is performed. Furthermore, areas of interest exposed for physical exploration in order to not miss important details that would have a direct impact on the prognosis. Pain is managed accordingly with analgesics and open wound fractures require treatment with a course of antibiotics. If necessary, the patient is given a tetanus shot.

The end of objective in the treatment of a zygomatic fracture is to ensure normal or near normal functionality. This includes the restoration of normal somato-sensory and masticatory function, as well as the cosmetic features of the face. Surgical intervention is not always necessary. This is especially true for stable and non-displaced zygomatic fractures, which require simple observation during healing. Surgery, if necessary, is done ideally within three weeks of the injury and involves closed or open reduction, and fixation with plates and screws. The prognosis, in general, is good.

References

Further Reading

Last Updated: Feb 27, 2019