Introduction

What is the Tdap vaccine?

Mechanism of action and immune response

Who should get the Tdap vaccine?

Health impact: What the Tdap vaccine protects against

Safety and side effects

Recent news and updates

Public health implications

Conclusions

References

Further reading

As vaccine-preventable diseases re-emerge, the Tdap vaccine remains a cornerstone of maternal and public health, protecting both newborns and communities through timely immunization and booster strategies.

Image Credit: Leigh Prather / Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: Leigh Prather / Shutterstock.com

Introduction

This article explains how the Tdap vaccine protects against tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis, addresses the issue of waning immunity, and emphasizes the crucial role of this vaccine in preserving public health for all age groups, particularly pregnant women and caregivers.

What is the Tdap vaccine?

The Tdap vaccine protects both children and adults from three bacterial infections, including diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis. In comparison to the pediatric diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis (DTaP) vaccine, Tdap contains lower doses of diphtheria and pertussis components, making it suitable for individuals 10 years of age and older.

In 2005, the Tdap vaccine was approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to mitigate rising pertussis cases and concerns over waning immunity. Currently, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends a Tdap booster dose every 10 years and during each pregnancy to ensure continued protection.2

Mechanism of action and immune response

The Tdap vaccine generates immunity by using inactivated toxins, also known as toxoids, for tetanus and diphtheria, along with purified antigens for pertussis, including pertussis toxin, pertactin, filamentous haemagglutinin, and fimbriae. After the vaccine is administered, the host immune system initiates the production of antibodies and antitoxins that target these antigens, a critical step in establishing adaptive immunity.1,2,3

Although the Tdap vaccine is initially highly effective, immunity decreases over time, especially against pertussis. This waning protection is particularly evident when comparing the modern acellular pertussis vaccine to older whole-cell versions. 1,2,3

Herd immunity protects individuals who cannot be vaccinated, such as newborns or those with weakened immune systems, by providing protection to those who can be vaccinated. However, because acellular vaccines may not always prevent the spread of infection, herd immunity alone is not sufficient. Therefore, maintaining high vaccination coverage and timely booster doses are critical.1,2,3

Who should get the Tdap vaccine?

Pregnant women are advised to receive the Tdap vaccine between 27 and 36 weeks of gestation during each pregnancy to transfer protective antibodies to their newborns. This maternal immunization significantly reduces the risk of pertussis in infants who are otherwise too young to be vaccinated.

The Tdap vaccine is also strongly recommended for healthcare workers, caregivers of infants, and individuals in close contact with newborns. Thus, routine Tdap vaccination across all age groups is critical for maintaining herd immunity and reducing the spread of preventable diseases.2,4

Tdap Vaccination During Pregnancy: What You Should Know

Health impact: What the Tdap vaccine protects against

Tetanus

Tetanus is caused by the bacterium Clostridium tetani, which produces a potent neurotoxin called tetanospasmin. Clostridium tetani can enter the body through wounds and survive in oxygen-poor environments like deep punctures.

Once inside, tetanospasmin disrupts communication between nerves and muscles, thereby leading to severe and often painful muscle spasms. Without immediate medical intervention, tetanus can be fatal, with mortality rates reaching up to 100% in untreated cases.

Today, most tetanus cases occur in individuals who are unvaccinated, inadequately vaccinated, or have not received a booster vaccine dose in the last 10 years.2,5

Diphtheria

Diphtheria is a rare but potentially fatal respiratory infection caused by Corynebacterium diphtheriae, a toxin-producing bacterium. Diphtheria primarily spreads through respiratory droplets or close contact with infected individuals.

Diphtheria can produce a thick gray pseudomembrane that adheres to the throat, which can subsequently cause an airway obstruction. Severe cases may result in heart and nerve complications once the toxin enters the bloodstream.

Although diphteria is rare in the United States due to high childhood vaccination rates, the risk of outbreaks increases when vaccination coverage declines or among international travelers returning from endemic areas.2.5

Pertussis (Whooping cough)

Pertussis is a highly contagious respiratory illness caused by infection with Bordetella pertussis. Pertussis, which is more commonly referred to as ‘whooping cough,’ often begins with mild cold-like symptoms until progressing to severe coughing fits followed by a high-pitched “whoop” sound.

Infants two months of age and younger are particularly vulnerable to the effects of pertussis, as they are at an increased risk of apnea, hospitalization, and death. Adults and adolescents with waning immunity can unknowingly transmit the infection to infants, thus emphasizing the importance of booster vaccinations and maternal immunization to protect this vulnerable pediatric population.2,5

Safety and side effects

The DTaP vaccine is administered in a five-dose series starting at six weeks of age and continues throughout early childhood. The vaccine contains inactivated toxins and purified pertussis components, which stimulate protective immunity.

Common side effects of the Tdap vaccine are often mild and can include pain, redness, and swelling at the injection site, while serious adverse events such as seizures or brachial neuritis are rare. Studies from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) and the CDC support the safety and long-term effectiveness of the Tdap vaccine.

Image Credit: SeventyFour / Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: SeventyFour / Shutterstock.com

Recent news and updates

High maternal vaccine coverage has been directly implicated in reducing the rate of infant hospitalizations and deaths caused by whooping cough. However, vaccine hesitancy has significantly contributed to declining vaccination rates and recent pertussis outbreaks in the United States and worldwide. These gaps in coverage are particularly evident in underserved communities, where access to healthcare and reliable information may be limited.6

To improve patient outcomes, the CDC has revised its recommendations to encourage Tdap vaccination between 27 and 36 weeks of pregnancy, which enhances the transfer of protective antibodies to the fetus. Simultaneously, scientists are developing new formulations of the vaccine that aim to provide durable immunity and improved effectiveness against changing strains of Bordetella pertussis. These advances support a broader effort to strengthen maternal immunization programs and improve public health for both mothers and infants.6

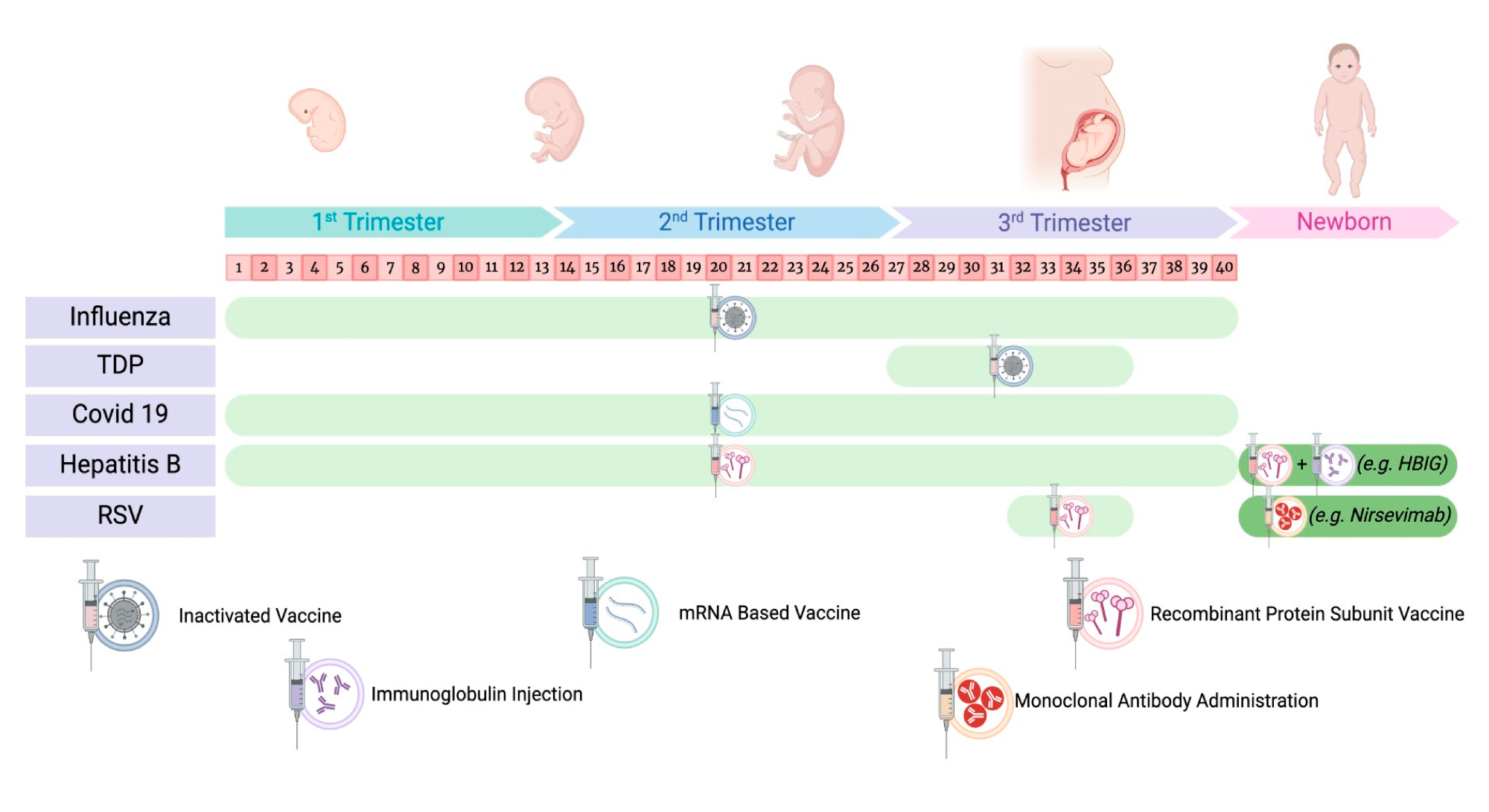

Recommended timeline of preventive measures during pregnancy and in the newborn.6

Recommended timeline of preventive measures during pregnancy and in the newborn.6

Public health implications

Adult vaccination, particularly against diseases like tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis, is crucial for proteting both individual and public health. However, declining uptake of the Tdap vaccine poses a serious threat, as reduced coverage can lead to increased disease transmission, particularly among individuals who cannot be vaccinated. Thus, expanding public education, improving vaccine accessibility, and addressing hesitancy through targeted outreach are essential approaches to strengthen adult immunization efforts and prevent outbreaks.7

Conclusions

The widespread administration of the Tdap vaccine is vital for protecting individuals and communities, particularly vulnerable patient populations like newborns and the immunocompromised. Booster vaccine doses remain essential, especially during pregnancy and for healthcare workers, to ensure sustained protection and prevent disease transmission.

Ongoing public education and clinical diligence are needed to maintain high vaccination rates. As immunity from earlier doses can wane over time, timely booster doses and adherence to updated guidelines is critical for preserving public health and avoiding rise of preventable diseases.

References

- Burdin, N., Handy, L. K., & Plotkin, S. A. (2017). What is wrong with pertussis vaccine immunity? The problem of waning effectiveness of pertussis vaccines. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology, 9(12), a029454. DOI: 10.1101/cshperspect.a029454, https://cshperspectives.cshlp.org/content/9/12/a029454

- Ogden, S. A., Ludlow, J. T., & Alsayouri, K. (2019). Diphtheria Tetanus Pertussis (DTaP) Vaccine. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545173/

- Pollard, A. J., & Bijker, E. M. (2021). A guide to vaccinology: from basic principles to new developments. Nature Reviews Immunology, 21(2), 83-100. DOI: 10.1038/s41577-020-00479-7, https://www.nature.com/articles/s41577-020-00479-7

- Cho, B. H., Acosta, A. M., Leidner, A. J., Faulkner, A. E., & Zhou, F. (2020). Tetanus, diphtheria and acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine for prevention of pertussis among adults aged 19 years and older in the United States: A cost-effectiveness analysis. Preventive medicine, 134, 106066. DOI: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106066, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0091743520300906

- Liang, J. L. (2018). Prevention of pertussis, tetanus, and diphtheria with vaccines in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR. Recommendations and reports, 67. DOI: 10.15585/mmwr.rr6702a1, https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/67/rr/rr6702a1.htm

- Santilli, V., Sgrulletti, M., Costagliola, G., Beni, A., Mastrototaro, M.F., Montin, D., Rizzo, C., Martire, B., Miraglia del Giudice, M. and Moschese, V. (2025). Maternal Immunization: Current Evidence, Progress, and Challenges. Vaccines, 13(5), 450. DOI: 10.3390/vaccines13050450, https://www.mdpi.com/2076-393X/13/5/450

- Kolobova, I., Nyaku, M. K., Karakusevic, A., Bridge, D., Fotheringham, I., & O’Brien, M. (2022). Vaccine uptake and barriers to vaccination among at-risk adult populations in the US. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics, 18(5), 2055422. DOI: 10.1080/21645515.2022.2055422

Further Reading

Last Updated: Jun 19, 2025