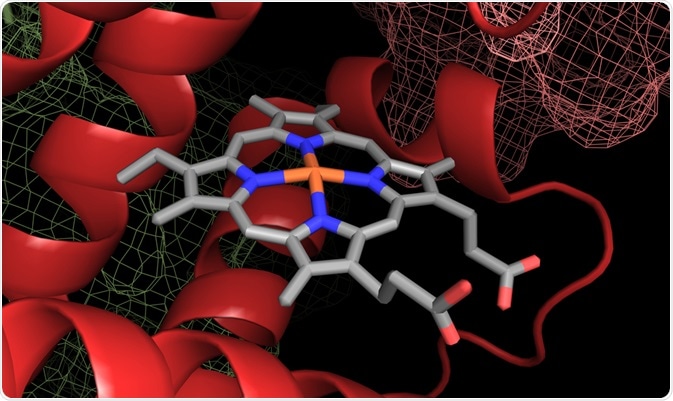

Heme is a coordination complex consisting of a porphyrin ring surrounding a single ferrous (Fe2+) or ferric (Fe3+) ion, able to bond with diatomic oxygen and transport it around the body.

A heme group in a hemoglobin protein structure. Image Credit: Catalin Rusnac / Shutterstock.com

A heme group in a hemoglobin protein structure. Image Credit: Catalin Rusnac / Shutterstock.com

The capture or release of oxygen is based on pH, with a distal histidine residue located above the iron ion becoming protonated under acidic conditions (caused by high CO2, in fatigued muscles for example) and undergoing steric reorganization, releasing the oxygen. Without oxygen bound the iron is in the 2+ state, but is oxidized to Fe3+ once bound, meaning that oxygen is in the form of a superoxide ion (O2-) when bound.

Four heme subunits compose one hemoglobin protein, and oxygen binding with one subunit pulls the iron ion into line with the plane of the porphyrin ring that causes a conformational shift that disrupts inter-dimer bonds between subunits, putting the molecule in a “relaxed” state that more easily accepts additional oxygen molecules. In this way, the four heme subunits work together to maximize oxygen loading and unloading efficiency.

Heme biosynthesis

Heme is generated in most tissues, though principally in erythroid cells and by hepatocytes, the most common cell of the liver. There are a total of eight enzymes involved in heme synthesis, half of which are found in the mitochondria and cytosol, respectively. The overall reaction in the generation of heme is:

8 glycine + 8 succinyl-CoA + 5 O2 + Fe2+ -> Heme + 8 CoA + 4 NH4 + 14 CO2 + 2 H2O2 + 2 H+ + 11 H2O

This process is separated into a number of steps, mostly taking place within the mitochondria. The rate of each step is dependent on the tissue producing heme, though the first step of the synthesis of intermediate 5-aminolevulinate is usually considered rate-limiting. The enzyme aminolevulinic acid (ALA) synthase catalyzes this first step, allowing the condensation of glycine with succinyl-CoA to form ALA and CO2 in the mitochondrial matrix.

ALA is subsequently transported to the mitochondrial inner membrane space, it is thought by transport protein SLC25A38. A second enzyme, porphobilinogen (PBG) synthase, then catalyzes the condensation of two ALA molecules to form one molecule of PBG. Four PBG molecules are then bound in a linear formation, head to tail, assisted by hydroxymethylbilane (HMB) synthase.

Uroporphyrinogen (URO) synthase then aids in attaching the top head group to the bottom tail group of HMB, forming a ring. The final enzyme that was produced in the mitochondria, uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase, aids in the decarboxylation of the four pyrrole acetic acid side chains remaining on URO, forming coproporphyrinogen III.

Coproprphyrinogen III is next transported to the mitochondrial intermembrane space by ABCB6, an ATP-dependant transporter. Two of the remaining carboxylic acid side chains are removed from the molecule, converting it into protoporphyrinogen IX (PP) by CP oxidase, which is produced in the cytoplasm and is weakly associated with the exterior of the outside of the mitochondrial inner membrane. PP oxidase then catalyzes the reaction of PP with three molecules of oxygen to create protoporphyrin IX, producing three molecules of hydrogen peroxide as a by-product.

Finally, ferrous iron is inserted into the protoporphyrin IX macrocycle, catalyzed by ferrochelatase, which is synthesized in the cytoplasm and later is translocated to the mitochondrial matrix and inner mitochondrial membrane.

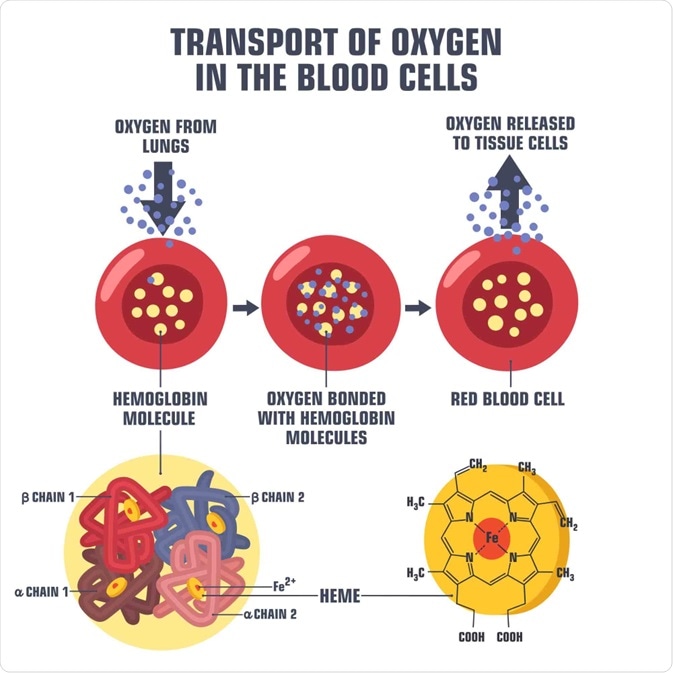

Diagram of oxygen transport in a blood cell. Image Credit: ShadeDesign / Shutterstock.com

Diagram of oxygen transport in a blood cell. Image Credit: ShadeDesign / Shutterstock.com

Clinical significance

Heme is largely synthesized in erythroid cells for incorporation into hemoglobin, which consists of four heme proteins. The kidneys produce a hormone called erythropoietin that stimulates the production of heme in the bone marrow.

As mentioned, some heme is produced by cells of the kidney itself, though the synthesis is highly variable and tightly modulated, with the heme produced contributing towards the synthesis of a number of other biomolecules besides hemoglobin such as cytochrome P450. It is also used by the body as an iron reservoir, by a number of enzymes as an electron shuttle, and is involved in cellular respiration, differentiation, and proliferation.

A deficiency at any point in the mechanism of the production of heme may lead to the accumulation of intermediates resulting in a range of disorders known as porphyrias, which may be related to production in the erythroid cells (erythropoietic) or hepatocytes (hepatic).

The symptoms of porphyria include neurologic dysfunction and respiratory problems, depending on the intermediate accumulating within the body. A deficient ferrochelatase enzyme, for example, leads to the accumulation of protoporphyrin IX in erythrocytes, resulting in extreme photosensitivity that leaves sun-exposed skin irritated and swollen.

Heme Synthesis Pathway — Biochemistry and Hematology

Further Reading

Last Updated: Jan 25, 2021