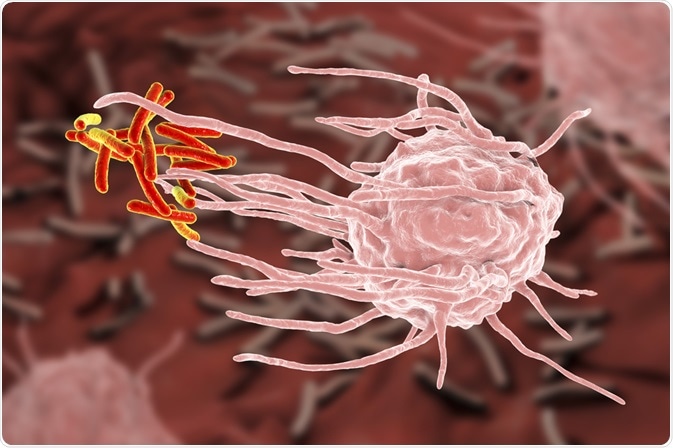

Phagocytosis is a form of endocytosis where a cell modifies its plasma membrane to engulf and internalize external matter, creating an internal compartment known as the phagosome. The word phagocytosis is derived from the Ancient Greek word “phagein”, meaning to eat.

Image Credit: Kateryna Kon / Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: Kateryna Kon / Shutterstock.com

During the process of phagocytosis, the cell can be described as ‘eating’ invading pathogens as well as dead tissue and cell debris as part of the body’s immune response to protect itself from illness.

Studies have shown that most cells are in fact capable of carrying out phagocytosis. However, immune cells known as “professional phagocytes”, such as macrophages, mature dendritic cells, and neutrophils are specialized in carrying out this process. These cells can contain, kill, and process microorganisms for antigen presentation.

The function of these cells is a vital part of the body’s innate immune response and also plays a fundamental part in stimulating the adaptive immune response. The process of phagocytosis, therefore, is vital to the proper functioning of the immune system.

The mechanisms of phagocytosis

At the beginning of phagocytosis, specific molecules or opsonins on the surface of the invading pathogen bind to the receptors on the cell surface of the phagocyte. This initiates receptor clustering, triggering phagocytosis.

At this point, the cell membrane modifies itself, extending and closing itself around the target, then finally breaking off to create a phagosome, a vesicle created from the cell’s membrane that contains the engulfed target. The phagosome interacts with the late endoscopes and lysosomes to create a phagolysosome, and within this vesicle, the engulfed contents are broken down via lysosomal hydrolases.

Receptors play an important role in phagocytosis, with a range of receptor types being implicated in the process, perhaps the most important of these being complement receptors and Fc receptors. These two types of receptors are key to the recognition and phagocytosis of microbes. Additionally, lectin receptors, scavenger receptors (SR), and Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are vital to the uptake of pathogenic microorganisms.

Pathogen-associated and endogenous molecules, such as cytokines and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) impact the process of phagocytosis. Specifically, TNFα and IFNγ are known to influence the formation and maturation of the phagosomes, having the effect of enhancing the activation and migration of other immune cells towards the site of infection, boosting the immune response.

Finally, studies have shown that some intracellular pathogens have evolved to be able to inhibit the process of phagosomal maturation, allowing them to remain within the cell for extended periods where they can replicate. Other pathogens have evolved other strategies to allow them to survive without destruction via phagocytosis, E. coli, for example, has evolved to be able to degrade opsonins to stop them from activating an immune response.

The role of phagocytosis in cancer

Phagocytosis plays an important role in protecting the body from cancer. As described above, phagocytosis is vital for removing pathogens as well as dying cells and aberrant cells such as cancerous cells.

Usually, dendritic cells will ingest and destroy cancerous cells and display their proteins on their cell surfaces to initiate a wider immune response, drawing in other immune cells to respond to the threat, helping them to better recognize and target the harmful cancer cells.

Unfortunately, some tumors avoid detection and destruction by macrophages by manipulating them. Sometimes, cancerous cells are able to hijack the macrophages and enlist them in helping cancer to proliferate.

Scientists have long understood this pathway and have developed targeted immunotherapies to fight back. These therapies target the macrophages to ensure that they are not compromised by the invading cancer cells, and they continue to do their job of identifying, targeting, and destroying harmful cells.

Some of these therapies work by targeting the CD47 receptor. Research has shown that cancer cells often over-express this receptor to instruct macrophages rather than to destroy them. To address this, immunotherapies have been developed that block CD47 receptors in order to prevent cancer cells from hiding from macrophages in this way.

In addition, other studies are exploring the role of innate immune checkpoints in mediating the identification and targeted destruction of cancer cells. Evidence shows that the innate immune checkpoints are also vital to the tumor-mediated immune escape.

It is suggested that because of this role, innate immune checkpoints may present an attractive target for cancer immunotherapy. Early studies have demonstrated that targeting phagocytosis checkpoints, like the CD47–signal-regulatory protein α (SIRPα) axis, may be effective at preventing the spread of certain cancers.

Research continues to explore the underlying mechanisms of phagocytosis. In particular, research will focus on how these mechanisms are implicated in the establishment and proliferation of tumors.

As our understanding of the pathways involved in phagocytosis advances, so will the sophistication of targeted immunotherapies for cancer, which will, hopefully, have the impact of improving the prognosis for various types of cancer.

Sources

Feng, M., Jiang, W., Kim, B., Zhang, C., Fu, Y. and Weissman, I., 2019. Phagocytosis checkpoints as new targets for cancer immunotherapy. Nature Reviews Cancer, 19(10), pp.568-586. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41568-019-0183-z

Rosales, C. and Uribe-Querol, E., 2017. Phagocytosis: A Fundamental Process in Immunity. BioMed Research International, 2017, pp.1-18. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5485277/

Smolle, M. and Pichler, M., 2017. Inflammation, phagocytosis and cancer: another step in the CD47 act. Journal of Thoracic Disease, 9(8), pp.2279-2282. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5594199/

Uribe-Querol, E. and Rosales, C., 2020. Phagocytosis: Our Current Understanding of a Universal Biological Process. Frontiers in Immunology, 11. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2020.01066/full

Further Reading

Last Updated: Dec 22, 2020