For many decades, humans have polluted the environment. The resultant toxic waste has been attributed to the development of a number of serious illnesses and health problems, such as cancer, diabetes, developmental illnesses, endocrine disruption, kidney damage, liver damage, and potentially heart disease.

Image Credit: dimitris_k/Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: dimitris_k/Shutterstock.com

To tackle this major health and environmental issue, scientists have developed a strategy to clean up toxic waste using naturally occurring and genetically modified microbes to degrade toxic substances so that they are no longer harmful. This strategy is known as bioremediation.

What is bioremediation?

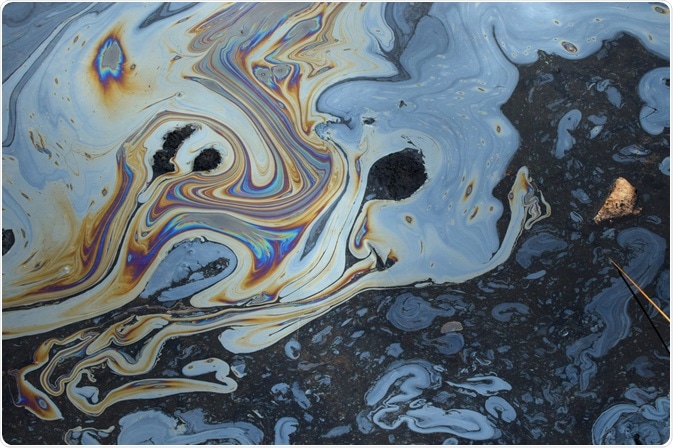

Bioremediation is essentially the biodegradation of toxic waste using microbes. The microbial cleanup of toxic waste is relatively new; however, studies have already shown its success in initiating the biodegradation of various types of toxic waste, chemical waste, including oil spills, mercury, radioactive waste, and even toxic electrical waste, converting these dangerous substances into safer compounds with the use of bacteria.

New bioremediation research is continually developing, with new applications of this form of microbial clean-up emerging each year.

One of the major natural roles of microbes is assisting in the process of decomposition. Microbes naturally facilitate the breakdown of organic material that is an essential process in the life cycle. Because it is their naturally evolved function, microbes are very good at facilitating decomposition.

Because of this, for a number of years scientists have been exploring how to leverage microbial decomposition to help degrade dangerous substances into harmless ones that pose a threat to the environment and to human health. This has led to the field of science known as bioremediation.

What impact will bioremediation have on the planet and human health?

Already, there are many studies that have demonstrated how microbes can be effectively leveraged to clean up various kinds of toxic waste. Here we discuss perhaps the most useful and innovative of these studies.

A decade ago, a team of scientists at the Inter American University of Puerto Rico modified E. coli bacteria so that it could survive in mercury, a highly toxic element, and degrade it. To do this, the team added genes to the E. coli bacteria that allowed it to produce metallothionein and polyphosphate kinase, proteins that give the bacteria resistance to mercury. This resulted in the bacteria being able to accumulate large quantities of mercury, isolating it and removing it from the environment.

Currently, there are no other known natural organisms that can degrade mercury. Therefore, this research is of great significance as it is the first to demonstrate how a natural organism can be adapted for the bioremediation of mercury, a highly dangerous substance.

Interestingly, while there are no other natural organisms that downgrade mercury, there are several that transform it into a more dangerous substance known as methylmercury. Often, at industrial sites ionic or elemental mercury is discharged and converted into methylmercury by microbes, which then accumulates in the environment and enters the food chain.

The genetically modified bacteria developed by the team at the Inter American University of Puerto Rico could address this issue by degrading the mercury discharged at such sites before it is converted into methylmercury. To achieve this, the team is developing a method of adding their modified bacteria into water filters at industrial sites, to remove the mercury from the water before it enters the surrounding environment.

In addition to reducing the pollutants released into the environment by industry, bioremediation has also been proven to be effective at cleaning up oil spills. The clean-up of the Exxon Valdez and oil spill and the Deepwater Horizon disaster were both assisted with the help of pollution-eating bacteria.

However, research has demonstrated that care should be taken when approaching oil spills with bacteria, as microbes that are not adapted to the environment die on being introduced to it, therefore, providing a source of nutrients to help the indigenous bacteria thrive. Scientists suggest that the best use of bacteria in cleaning up oil spills is not to directly add them in but to assist the bacteria that are already naturally working on breaking down the oil.

There are already communities of microbes capable of degrading oil due to natural oil seeps in various parts of the world, such as the Gulf of Mexico. These microbes can be assisted in their natural jobs by adding nutrients to the water near an oil spill to help grow these specific microbial populations. This technique has been further developed to help clean up other kinds of toxic easter, such as in breaking down chlorinated solvents.

Bioremediation: How biology heals the earth naturally | Shaily Mahendra | TEDxManhattanBeach

The future of microbial biodegradation of toxic waste

The use of microbes in cleaning up toxic waste is growing. Scientists are continuing to explore how the natural functions of microbes can be leveraged to help degrade toxic substances that threaten our environment and public health.

Currently, microbes have been developed in a number of ways to help degrade a wide range of toxic substances such as chemical waste, oil spills, mercury, radioactive waste, and toxic electrical waste. In the coming years, we can expect further developments and new applications of microbes in toxic clean-ups.

Sources

- Mani, S., Chowdhary, P. and Zainith, S., 2020. Microbes mediated approaches for environmental waste management. Microorganisms for Sustainable Environment and Health, pp.17-36. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780128190012000024

- McCreary, E., Akgerman, A., Autenrieth, R. and Bonner, J., 1989. Microbial degradation of hazardous wastes to non-toxic end-products. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 22(2), pp.254-255. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/0304389489850551

- Ruiz, O., Alvarez, D., Gonzalez-Ruiz, G. and Torres, C., 2011. Characterization of mercury bioremediation by transgenic bacteria expressing metallothionein and polyphosphate kinase. BMC Biotechnology, 11(1). bmcbiotechnol.biomedcentral.com/.../1472-6750-11-82#citeas

Further Reading

Last Updated: May 17, 2021