Bacteriophages are small, virus-like organisms that infect bacteria. They are comprised of a protein capsule around an RNA or DNA genome.

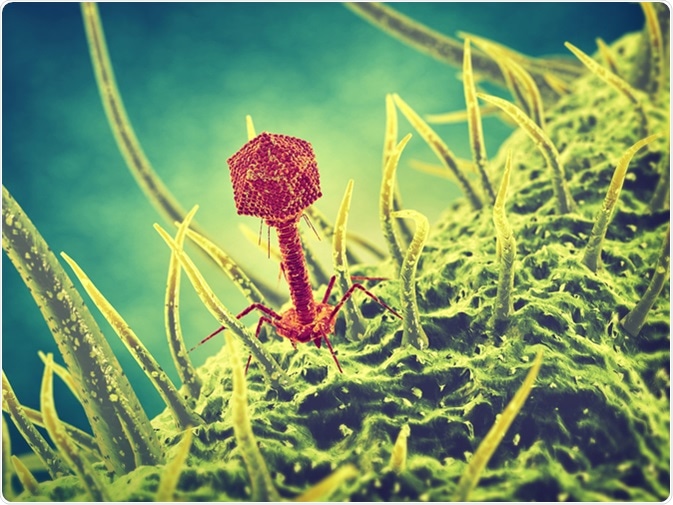

Bacteriophage virus illustration. Image Credit: nobeastsofierce / Shutterstock

The bacteriophage structure may include various features for infecting the host cell. Many bacteriophages have a central shaft and leglike appendages. The legs attach to the bacteria, and genetic material is injected through the shaft into the host cell cytoplasm, where it replicates and reassembles into progeny.

The bacteriophage life cycle is either lytic or lysogenic. Lytic phages, like T4, lyse the host cell after replication of the virion. The phage progeny are then released to find new hosts.

Lysogenic phages do not immediately lyse the host cell. These phages are known as temperate phages. The bacteriophage genome integrates with the host genome and replicates with it, without destroying the cell. When conditions deteriorate for the host cell, such as a lack of nutrients, the phages initiate the reproductive cycle, resulting in lysis.

Bacteriopage Lytic Cycle

Life Cycle of the Bacteriophage

The life cycle of the bacteriophage consists of several steps:

- attachment and penetration

- synthesis of proteins and nucleic acid

- virion assembly

- release of virions

Attachment and penetration: Bacteriophages attach to receptors on the outside surface of the bacteria. Those include lipopolysaccharides, teichoic acids, proteins, or flagella. Many bacteriophages employ a mechanism rather like a hypodermic syringe to inject genetic material into the cell through a tail-like structure.

Synthesis of proteins and nucleic acid: Bacterial ribosomes translate viral mRNA into protein. If the bacteriophage has an RNA genome, RNA replicase is synthesized early in this process. Host RNA polymerase is recruited to preferentially transcribe viral mRNA, interrupting the normal synthesis of host proteins. The proteins are assembled into new virions.

Virion assembly:Helper proteins are often used to assemble the virus particles. They are put together piece by piece, base plates, tails and head capsids, with DNA packed inside.

Release of virion:Newly assembled bacteriophages are released by lysis, extrusion, or budding.

Bacteriophage Therapy

Being natural predators of bacteria, bacteriophages have been long considered as potential therapeutic agents. There are many reports of phage therapy used in humans. In a study of 550 patients with bacterial septicemia, phages were administered orally, topically, or to the eye, ear, or nose. Success rates for treatment ranged from 75 to 100 percent. The efficacy was even higher among patients who had not responded to antibiotic therapy.

Phages have also been effective for:

- cerebrospinal meningitis in a newborn skin infections due to Pseudomonas, Staphylococcus, Klebsiella, Proteus, and E. coli.

- recurrent subphrenic and subhepatic abscesses

- chronic bacterial diseases

Phage therapy has also been found to normalize tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) levels in serum.

Safety of Bacteriophage Therapy

Bacteriophages appear to be largely innocuous when used clinically. In the U.S. phage phi X174 is used to monitor humoral immune function in adenosine deaminase-deficient patients, and to study human immune response. Phages are very common in the environment and in foods, and are associated with illness or injury. Safety considerations in therapeutic agents are that they should not trigger generalized transduction or have gene sequences with significant homology to known major antibiotic resistance genes, phage-encoded toxin genes, and genes for bacterial virulence factors.

Further Reading

Last Updated: Feb 26, 2019