Spheroplasts are cells (fungal, plant or bacterial) with partial cell wall. They can be found naturally and in the laboratory.

Origin

The name “spheroplast” comes from the circular shape which is adopted by bacterium after removal of its cell wall. This circular shape aids its survival in harsh environments. Despite this structural alteration, these cells are extremely susceptible to environmental stress, such as osmotic and mechanical shock. For example, the peptidoglycan wall in bacteria usually functions to respond to the different ionic concentrations within and outside the cell. Loss of this layer leads to loss of this protection and sensitivity to osmotic stress.

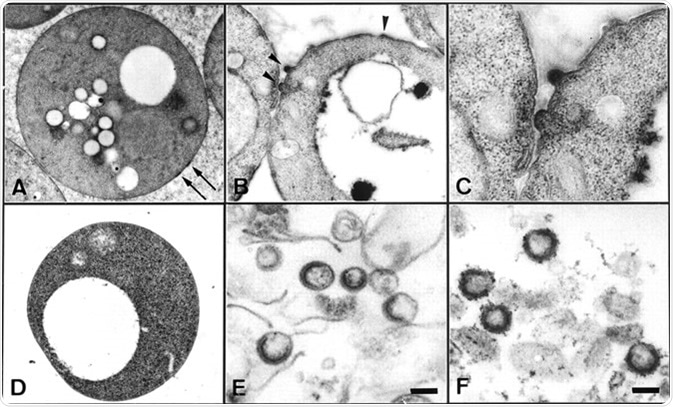

Electron microscopic examination of yeast spheroplasts expressing HIV Gag protein and VLPs purified from the culture medium. (A–C) Yeast spheroplasts expressing Gag protein. Image Credit: PNAS

The Formation of Spheroplasts

The precise method used to form a spheroplast depends on the type of cell. For example, fungal cells can form spheroplasts after chitinase treatment, whereas plant cells form spheroplasts following pectinase, cellulase, or xylanase treatments. As bacterium spheroplasts are susceptible to osmotic pressures, their formation must be carried out within an isotonic solution. If the concentration of the solution is higher outside of the bacterial cell, water would enter the bacterium, resulting in swelling and eventual cellular bursting. Conversely, if the concentration is higher inside the cell, the water would leave the bacterium, resulting in cellular shriveling and eventual death.

Penicillin treatment

Penicillin a type of β-lactam antibiotic which prevents peptidoglycan links during the biosynthesis of the cellular wall. Therefore, when the bacterium is treated with this antibiotic, it cannot form a stable outer layer and becomes susceptible to osmotic pressures. The bacterium can also form spheroplasts after lysozyme treatment which degrades the cell wall. Spheroplasts can also be found outside of the lab and are termed “L-phase bacterium”. Many types of bacteria have been identified to have L-phases, including Pseudomonas, Staphylococcus, Clostridium, and Bacillus.

Spirochetes turn into L forms or spheroplasts

Applications of Spheroplasts

Antibiotic characterization

If a bacterium forms spheroplast after drug treatment, then the antibiotic must work through inhibiting the biosynthesis of the cellular wall. This methodology has led to the discovery of many antibiotics, such as cephamycin C, carbapenems, and fosfomycin.

Patch clamp analysis

Giant spheroplasts (formed by prevention of cell division) can be used in patch clamp analysis, which is useful to characterize bacterial ion channels. This method monitors the current through an ion channel. While a singular bacterium is too small for this assay, these giant spheroplasts are large enough to allow patch-clamp recording. These giant spheroplasts are grown in the presence of cephalexin, which prevents the cell from splitting and dividing, leading to the formation of “snakes” with a singular membrane and cytoplasm. The cell walls of these ‘snakes’ can be removed and the resultant spheroid can be used in the patch-clamp analysis.

Transfection

The cell wall usually hinders the transfection process, and therefore, by inserting a recombinant DNA into a spheroplast, a vector is created which can transfect the animal cells with improved efficiency.

Summary

Spheroplasts are cells without an external cell wall, which can occur naturally or can be created within a laboratory. They are invaluable in antibiotic characterization, patch-clamp analysis, and transfection assays.

Further Reading

Last Updated: Oct 24, 2018