Apr 19 2005

A Johns Hopkins study finds that people who have a family history of heart disease have more reason than most to keep their weight down. In these families, the Hopkins team found that siblings who were obese or overweight had a 60 percent increased risk of suffering a serious heart ailment, such as a heart attack, before the age of 60.

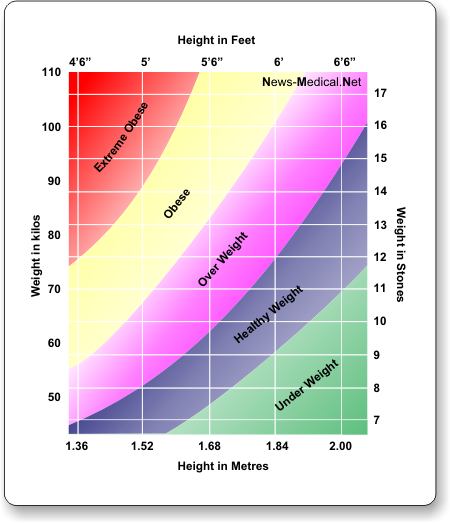

The study, to be published in the journal Circulation online April 19, is believed to be the first measure of additional risk from increased body mass index (BMI) in such populations (BMI equals weight in kilograms per height in square meters). People are considered to be obese when their BMI is greater than or equal to 30 kilograms per meter squared; overweight is defined as a BMI of 25 to 29.9 kilograms per meter squared. For example, someone who is 5 feet 10 inches tall who weights 250 pounds has a BMI of 41 kilograms per meter squared.

"There is a growing epidemic of obesity among Americans, with two-thirds of Americans overweight," says senior investigator Diane Becker, M.P.H., Sc.D., a professor at The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and Bloomberg School of Public Health. "Because overweight and obesity are risk factors for heart disease, physicians and the public should know what additional risk applies for siblings in families with known heart problems so that appropriate monitoring and therapy can be performed."

The study's results highlight the importance of BMI in assessing overall risk to heart health and supplement traditional risk assessments, such as the Framingham Risk Score (FRS), the researchers say. Traditional FRS scoring measures the likelihood of developing major heart problems, such as a heart attack, within 10 years. However, the FRS score, originally developed in the 1990s, omits BMI, taking into account traditional leading risk factors for heart disease, such as age, gender, cholesterol levels, blood pressure, smoking and diabetes.

In the Hopkins study, researchers monitored risk factors, both traditional and BMI, for nine years in 827 siblings under age 60 from families in the Baltimore region. Study participants were generally healthy at the beginning of the study, with no early signs of heart disease, but all had at least one major risk factor. Every participant also had at least one sibling with premature coronary heart disease (such as blocked arteries) that had required hospitalization, so family history was a risk factor. Half of participants were women, 20 percent were black Americans and the rest were predominantly white. Blood tests and physical exams were conducted at the beginning and end of the study to assess changes in each individual's risk factors.

Results showed that 13.3 percent of siblings had a premature incident of heart disease within a nine-year period. Of these, obese and overweight siblings had similarly higher incident rates of 15.3 percent and 16 percent, respectively, double the rate in siblings with a normal weight. According to Becker, this translates into a 4 percent increase in risk of coronary heart disease for every one-unit increase in BMI.

Indeed, obesity was found to have the greatest impact on risk of heart disease in siblings who had multiple risk factors that gave them a high FRS score. In this group with a high FRS score, obese siblings had twice the amount of coronary heart disease as those who were overweight - 40 percent and 20 percent, respectively - and double the rate in siblings with normal-weight siblings. When compared to siblings with low FRS scores and normal weight, obese siblings with high FRS scores had 15 times more premature heart disease.

When genetic traits were analyzed, the Hopkins team found that 50 percent of BMI in whites was hereditary, while in blacks, the hereditary factor was even less, at 30 percent. This means that lifestyle and environmental factors account for the rest, the researchers say, suggesting that much of BMI is not associated with family history and, as a result, it can be changed and improved.

"Our results show that obesity is far more important than previously thought to gauging real risk of heart disease in families where this is already a problem," says the study's lead author, cardiologist Samia Mora, M.D., M.H.S., then a research fellow at Hopkins. "When monitoring these patients with traditional Framingham Risk Scores, physicians should also closely monitor body mass index, even when it is mildly elevated, and incorporate weight reduction programs into treatment plans accordingly. These siblings really need to watch their weight. Fortunately, it is a risk factor that can be modified."

Results from the study could not fully explain the strong link between obesity and premature heart disease. Further research is planned to verify its biological and genetic origins.